Preventing diabetes: Mother-daughter duo reverse prediabetes together with Mount Carmel program

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A few years ago, Diane Turner Jackson went to the drug store to pick up medication for her uncle and was given insulin.

Confused, she confronted him about his illness, but he pleaded ignorance.

It was only when Turner Jackson opened Eddie Parker's closet door did it dawn on her that her uncle had been living with Type 2 diabetes for an untold number of years and had expertly kept his condition secret from family and friends.

Inside the closet were dozens upon dozens of unused syringes and bottles full of insulin.

"They were mailing it to him and he was putting it in his closet," Turner Jackson said, sitting on the couch of her South Linden home that she shares with her mother.

"He started to use it and he knew how to check his blood, but somewhere (along the way) he shut down completely."

Health: Ohio nearly last in US for health, report shows

Diabetes hits home

Upon this discovery, Turner Jackson said she quickly sprang into action and became Parker's primary caregiver.

She and her cousins began taking him to medical appointments, giving him shots of insulin, and caring for him when his condition worsened and he was admitted to the hospital.

During his stay, Parker developed peripheral edema, or swelling in the feet, ankles and legs.

He became delirious from multiple urinary tract infections and would pull out his PICC line, a catheter that's inserted into a vein in the upper arm to give medications or liquid nutrition.

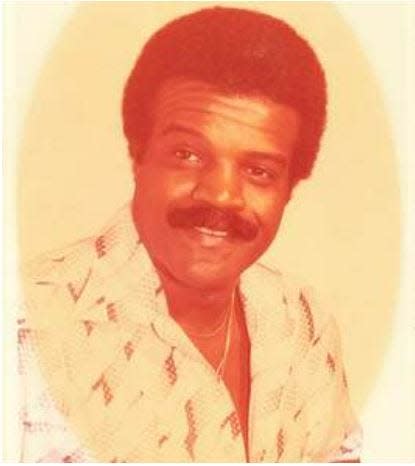

Parker ultimately died of complications of diabetes on Feb. 11, 2020, the night before he was to be released from the hospital, to be cared for by his wife at home. He was 81.

Parker's death was one of the main reasons Turner Jackson, 66, and her 85-year-old mother, Shirley Turner, signed up for a free diabetes prevention program offered by Mount Carmel Health System.

Last fall, they discovered within a month of each other that they both were prediabetic, or at risk of developing the chronic health condition in which the body either doesn't make enough insulin or can’t use the insulin it makes as well as it should.

In 2018, nearly 1 million Ohioans, about 11% of the state's population, were diagnosed with diabetes, according to the state health department. That's on top of 750,000 adults in Ohio who had been diagnosed with prediabetes, with an estimated 1.3 million prediabetics that had not been diagnosed.

Insulin regulates the amount of glucose, or sugar, in the bloodstream. Too much glucose can lead to serious health problems, such as heart disease, vision loss and kidney disease, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"I thought, 'I don't want my mother to ever go through this. I don't want anybody in our family to go through this,'" Turner Jackson said.

Health: Wearing a mask is good but getting a flu shot is better

What is prediabetes, exactly?

Kelvin Ruffin, 49, has had Type 2 diabetes for about a third of his life.

He's a community health worker for Mount Carmel who coached Turner Jackson and her mother over the phone on how to reverse their prediabetes through diet changes and weight loss.

Ruffin said someone is considered to have prediabetes if their blood sugar levels are high, but not high enough for someone to be considered diabetic.

"Your A1C is what they're going to look at. If your A1C is between a 5.7 and 6.4%, you're considered prediabetic," he said, referring to the blood test that measures your average blood-sugar levels for three months.

Once someone is diagnosed with prediabetes, they need to lose between 5% to 7% of their body weight — about 10 to 14 pounds for a 200-pound person, Ruffin said. They can do this by changing their diet and taking part in at least 30 minutes per day of moderate activity, he added.

As a diabetic, Ruffin suffers from neuropathy, or nerve damage in his feet and has an eye disease that can cause blindness. "I have to get my eyes checked quite often," he added. "Now, not everybody will experience that. But some people might."

He's been with Mount Carmel's prevention program since its inception in January 2018.

"I really don't want people to suffer the way I have," Ruffin said. "If I can help one person delay or prevent Type 2 diabetes, I think I'm doing a pretty amazing job."

Health: Chicken soup, tea with honey: Do grandma's cold and flu remedies really work?

Mount Carmel's free, 26-hour program is among a handful of programs in Greater Columbus dedicated to the prevention of diabetes. Once someone receives a diagnosis of prediabetes, Mount Carmel connects them with a community health worker, such as Ruffin, who counsels them on how to alter their lifestyle.

LifeCare Alliance can offer consultations with dietitians for those with prediabetes, provided their insurance covers their diagnosis, said Elana Burak, case manager of wellness for the Columbus nonprofit group. Prediabetes consultations are not covered by Medicare of Medicaid, she added.

Ohio State University's Wexner Medical Center also offers a self-management education program to those with prediabetes, according to its website, though patients must get a physician's referral before being scheduled for classes.

To prevent diabetes, eat out less and cook at home

As part of Mt. Carmel's prevention program, Ruffin instructed Turner Jackson and her mother to chronicle the number of grams of carbohydrates, calories, sodium and sugar they consumed each day.

He provided a cheat sheet that warned them what to watch out for, ingredient-wise, and told the pair to steer clear of processed and fast food and to cook at home more often.

That proved to be a small challenge because the mother-daughter duo love to eat out. But moderation is key.

"Every now and then, I will eat a piece of Popeye chicken," Shirley said with a smile.

Not much changed as far as the types of meals Turner Jackson and her mother cook at home, but the ingredients did.

"Kelvin told us we can eat anything we wanted. We just had to read the label," Turner Jackson said. "And that was the key thing."

Sweets were another story.

"Cookies, cookies cookies," Turner Jackson said, pointing to Shirley, who rolled her eyes in her daughter's direction. "I had to say, 'Mom, we've got to push those cookies away. Let's not buy anymore cookies or ration them out.' So that's where the reading of the labels really came handy for us."

The pair stay active by using the 200-meter elevated walking track at the new Linden Community Center.

Regular checkups crucial

Turner Jackson shudders at the thought of not knowing that she and her mother were prediabetic until they got the diagnosis. They encourage all Ohioans to get regular checkups.

"Don't be afraid to find out," Turner Jackson said. "Push past the fear, because in the long run, it will be in your best interest. It can be like a time bomb and you're not even aware of it.

"We need to know. We need to be advocates for ourselves."

Monroe Trombly covers breaking and trending news for the Dispatch. He can be reached at mtrombly@dispatch.com or 614.228.6447. Follow him on Twitter @MonroeTrombly.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Diabetes prevention: Mount Carmel program helps mother, daughter