The Priest Who Summited North America’s Highest Peak

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Hudson Stuck could barely breathe. A tough and experienced outdoorsman who had spent the last decade dogsledding and tramping across Alaska and the Yukon, Stuck nevertheless gasped in the high, thin air 20,000 feet above sea level.

He and his three companions stood just below the summit ridge of Denali, the highest peak in North America, on a clear, windy, 4°-below day. Stuck wore six pairs of socks inside his leather moccasins, with iron “ice-creepers” or crampons attached to the bottom. Immense lynx-fur-lined mitts covered inner Scotch-wool gloves, and his torso was layered beneath a fur-hooded Alaskan parka. “Yet,” Stuck wrote, “until high noon feet were like lumps of iron.”

Behind them stretched what Stuck called the “dim blue lowlands” of the future Denali National Park, “with threads of stream and patches of lake that still carry ice along their banks.” A few smaller peaks squatted off to the northeast. In every other direction, the immensity of the mountain they perched on blocked their views of Mount Foraker and the other peaks in the Alaska Range. Above them, just a few hundred more yards of climbing and the prize—to be the first humans to set foot atop Denali—would be theirs.

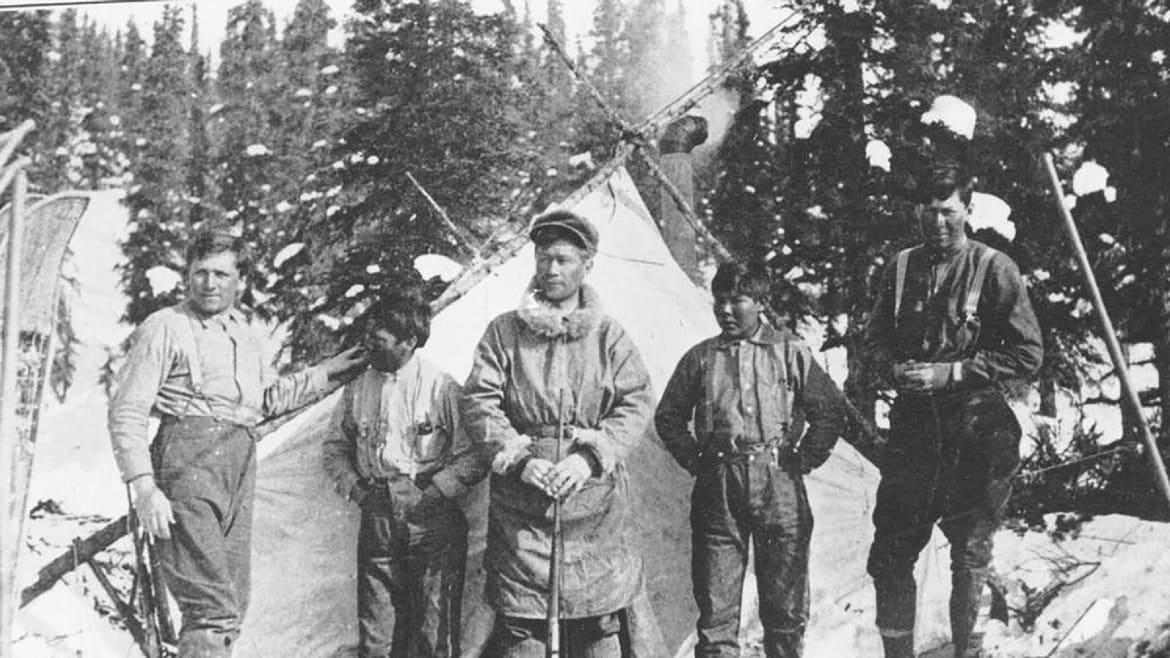

Rev. Hudson Stock (1865 - 1920) (left) and Harry P. Karstens, who made first ascent of Mt. McKinley, September 1913.

It was June 7th, 1913. They were Stuck, Episcopal Archdeacon of Alaska and the Yukon, the oldest of the group at nearly fifty years old, short and wiry, his neatly-trimmed beard the only one among the four; Walter Harper, the youngest at age twenty, half Alaskan Native, fit and confident; Harry Karstens, thirty-four, calmly competent from his years in the Alaskan backcountry; and Robert Tatum, twenty-one, the greenest member of the team. They had launched this expedition eight weeks earlier, enduring bitter cold, severe altitude, and the loss of key supplies to a campfire.

The team had arrived at their last camp, just below 18,000 feet, the night before. Awakening to a brilliant, bitterly cold morning, the party had reached the summit slope after eight grueling hours, with Harper in the lead. Surrounded by nothing but snow and ice, their toes and fingers numb, they approached the final ridge to the summit.

Though all the men were unable to fully take in air—“it was curious to see every man’s mouth open for breathing,” Stuck would later write—it was hardest for him. Everything kept turning black for Stuck as he choked and gasped, almost unable to get any breath at all. The missionary’s load had already been reduced; the other members had divided up the contents of his pack, leaving him only the bulky mercurial barometer he had stubbornly carried up the mountain to make scientific observations on the summit. Now he struggled even under the barometer’s weight. Finally, Harper, the youngest and strongest member of the expedition on this day, doubled back to where Stuck knelt in the snow, took the barometer and hoisted it onto his back.

Harper’s presence on the mountain was important to Stuck for more than just his youthful vigor and physical strength. Since coming to Alaska in 1904 to become Archdeacon of Alaska and the Yukon, Stuck had become a fervent champion of the rights of the Native people. In the Alaska of this era, a raucous and deeply unsettled meeting point between traditional Native ways and the modern white culture—“a center of feverish trade and feverish vice,” in Stuck’s words—Stuck spent most of his time ministering to the Athabascan peoples in his region. He bore no illusions that their lives would be improved by the onslaught of Western ways.

Harper, who was half Athabascan and half Irish, represented Stuck’s aspirations for the Natives of the Far North. Walter’s father, Arthur Harper, a distant figure in his life, was a pioneer in the history of white Alaska, the first to imagine gold in the Yukon, where he met Walter’s mother. Walter was raised by his mother in an Athabascan village and at sixteen met Stuck at the mission school in Tenana. They forged a lifelong connection. On Denali, in Stuck’s words, Harper “ran Karstens close in strength, pluck, and endurance.”

Robert Tatum was a Tennessean who had come to Alaska to study for Holy Orders in the Episcopal Church. He had proved himself the previous winter by joining a heroic relief effort, helping deliver by dogsled desperately-needed supplies to two women missionaries down the dangerous ice of the frozen Tanana River. His experience with surveying tools and other scientific instruments and his willingness to serve as the cook for the expedition, along with what Stuck termed “his consistent courtesy and considerateness,” made Tatum “a very pleasant comrade.”

Harry Karstens had been in Alaska for almost two decades, and learned its often-harsh lessons first-hand. He had earned the right to be considered a “Sourdough”—a term derived from prospectors’ habit of carrying a starter of sourdough bread in a pouch around their neck, later expanded to describe those who’d been in the Far North long enough to prove themselves. He had made his reputation in the backcountry since the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897, making his reputation on the mail routes, prospectors’ streams, and hunting expeditions of early-1900s Alaska. Stuck explicitly relied on Karstens for his outdoor skills and experience, as well as his toughness.

How did an Episcopal Archdeacon, well into middle age by the standards of the time, come to find himself in the freezing final summit push on the highest, coldest peak on the continent? The answer lay in two equally potent forces, woven into his being. Just as strong as Hudson Stuck’s belief in doing good—“I am sorry for a life in which there is no usefulness to others,” he once wrote—was his love of wild places. He had grown up reading the exploits of the polar explorers, thanks to the library of a relative lost at sea. As a youth Hudson Stuck had explored the mountains of his native England, including the Lake District peaks Scafell Pike (the highest mountain in England, at 3200 feet), Skiddaw, and Helvellyn. Although they weren’t much more than scrambles, much less technical climbs, they gave the youthful Stuck a glimpse of what could be found in the world’s high, wild places.

The twenty-two-year-old Englishman’s pursuit of change and adventure led him and a friend to leave England in 1885 and make their way by steamship to New Orleans, then to San Antonio. Stuck loved the stark beauty of the West Texas rolling prairie. Working as a cowboy and ranch hand, on horseback with his Remington rifle, he witnessed a vanishing world.

After three years of alternating teaching and ranch work, Stuck’s future path became clear. Always devout and with a keen sense of duty to serve others, his involvement with the Episcopal Church as a layman earned him a scholarship to the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, to study for the ministry.

Feeling expansive after his time in Sewanee, Stuck returned to Texas and a small parish church in Cuero. Before long, however, he was inevitably lured to the largest and most powerful church in the state: St. Matthew’s, the Episcopal Cathedral of Dallas. There, among his wealthy and influential parishioners, Stuck would first make a reputation—though not, in some quarters, a favorable one.

As dean of St. Matthew’s Cathedral, Stuck founded St. Matthew’s School for boys, a night school for mill workers, and a home for indigent young mothers. But when Stuck took up the reform of child-labor laws, he found himself at odds with the powers that be.

Even while fighting these battles as dean, Stuck continued his quest to challenge himself in the strenuous pursuit of natural, rugged beauty. He spent annual holidays in wild and mountainous places, from the Colorado Rockies and “the Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone” to the summit of Washington’s Mount Rainier.

Chafing under the direction of his more-conservative bishop in Dallas, Stuck jumped at the chance to work in Alaska. At last, he felt he had found a place and a job with scope for his ambitions, as well as the landscape of his wildest dreams. First in Fairbanks, and later in Fort Yukon, Stuck continued the work he had begun in Texas: building hospitals and schools as well as churches; founding libraries as alternatives to saloons; condemning the lax morals of the whites and their corrosive effects on the Natives of the North.

After accepting his new position in Alaska, he routed his trip north through the Canadian Rockies, climbing Mount Victoria, “my first snow mountain,” as well as reaching Glacier House on present-day Revelstoke. Stuck then sailed north from Seattle with stops along the Alaskan coastal range. Almost from the moment of his arrival in Fairbanks, Stuck began visiting his mission churches by dogsled in winter and by boat after the spring thaw, awed by the wild rivers and mountains, the Northern Lights, and the rugged grandeur of the high latitudes. His book about his winter trips, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dogsled, earned him acclaim in the Lower Forty-Eight and respect as an outdoorsman who was willing to visit his far-flung mission churches in the dead of the Alaskan winter.

Yet even as he criss-crossed his region by dogsled and boat, Hudson Stuck would catch a glimpse from time to time of Denali. The mountain, “the Big One” in the Athabascan language, was as yet unclimbed; with the arrival of prospectors in the 1890s it also acquired a new name, Mount McKinley. Thoughts of the glory and acclaim to be won from its first ascent never really left Stuck’s mind. When the persistent clouds cleared and he grabbed a glimpse of the mountain, the “splendid vision” made him ever more eager to “scale its lofty peaks.” For Stuck, Alaska was a place where his physical and spiritual aspirations, his goals for himself and for his mission, could be united into a single purpose. “I would rather climb Mount McKinley than own the richest gold mine in Alaska,” he claimed. He was not alone in his desire.

Composite image showing the front and back sides of a thermometer used by Hudson Stuck to record weather data during the Denali summit.

Given its status as the grandest peak in the Northern Hemisphere, Denali became one of the primary prizes of the age. This immense young mountain, geologically speaking—the Alaska Range at 5 to 6 million years old is far younger than the Appalachians or Rockies—sheds massive glaciers, largely on its southern flanks due to the accumulated moisture swept up from the North Pacific. Its height from base to peak, rising 18,000 feet from the plain, is several thousand feet more than that of Everest. In addition, due to its position as the northernmost 6,000-meter mountain in the world, Denali’s weather is extremely hazardous, to say the least. In 2003, a North American-record windchill of -118º F was recorded near the mountain’s summit; the next day, the same weather station recorded a temperature of -75.5º F. This ferocious, frigid massif was destined to become the next great prize in that era of exploration and discovery. The only question was who would be the first to claim its undisputed ascent.

Attempts to summit Denali had begun not long after whites first came into the country. The year before Stuck’s arrival in Alaska, the first notable expedition had been organized by Judge James Wickersham, who with a party of five men attempted to ascend by way of the northern face of the mountain in 1903. There they were stymied by the enormous ice-encrusted cliffs of the Peters Glacier.

Then came Dr. Frederick Cook from New York, who had parlayed experience in the Antarctic into a shot at Denali. On his second attempt, in 1906, he claimed the summit, and produced photo evidence. The claim isn’t acknowledged today, over a century later; most don’t believe Cook. Stuck, for one, flatly dismissed Cook’s claim.

So did a group of four Alaskans who would become known as the Sourdough Expedition of 1910. With no mountaineering experience but plenty of pioneer confidence, the Sourdoughs attempted to dash up Denali’s slopes to plant a flagstaff that would be visible in Fairbanks. Amazingly, they made it to the lower North Summit, though as with Cook, not everyone believed their account. And just the year before, Belmore Browne and Herschel Parker had been driven off the summit approach by bad weather, only 200 feet from the top.

Stuck and Karstens left Tenana two months behind schedule, on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1913. They aimed their dogsleds toward the mission at Nenana, stopping there to pick up Harper, Tatum, and two Indian boys who would help with the dogsleds. By April 11, they had reached the base of Denali and had their first glimpse of the Muldrow Glacier, the river of ice they planned to follow to the summit. Stuck named it “the highway of desire.”

Overcoming one setback after another—some natural, some man-made—the team made the first foray onto the Northeast Ridge toward the summit. Much to their dismay, the path up the ridge, which Belmore Browne had described as “a steep but practical snow slope,” was instead fractured and jumbled thanks to a 1912 earthquake. Slowly, laboriously, exhaustingly, Karstens led the effort to hack a safe three-mile path through the house-sized boulders and enormous ice sheets. What should have been a three-day climb up the ridge consumed three weeks. “Anyone who thinks that the climbing of Denali is a picnic,” wrote Stuck, “is badly mistaken.”

Now, on the clear morning of June 7, dressed in “more gear than had sufficed at 50° below zero on the Yukon Trail,” Stuck and the others turned toward the final slopes. The group made steady progress, with Harper in the lead and Stuck stumbling in the rear. As the four men stood, one behind the other, desperate for air, Denali’s South Peak lay within reach. The weather gods had blessed them with brilliantly clear, though numbingly cold, weather this day. Now it was up to them to take advantage of their luck.

Each man lifted a frozen, heavy foot, and, one after the other, took another step upward toward their goal.

Excerpted from A Window to Heaven: The Daring First Ascent of Denali: America's Wildest Peak by Patrick Dean. With permission from Pegasus Books.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.