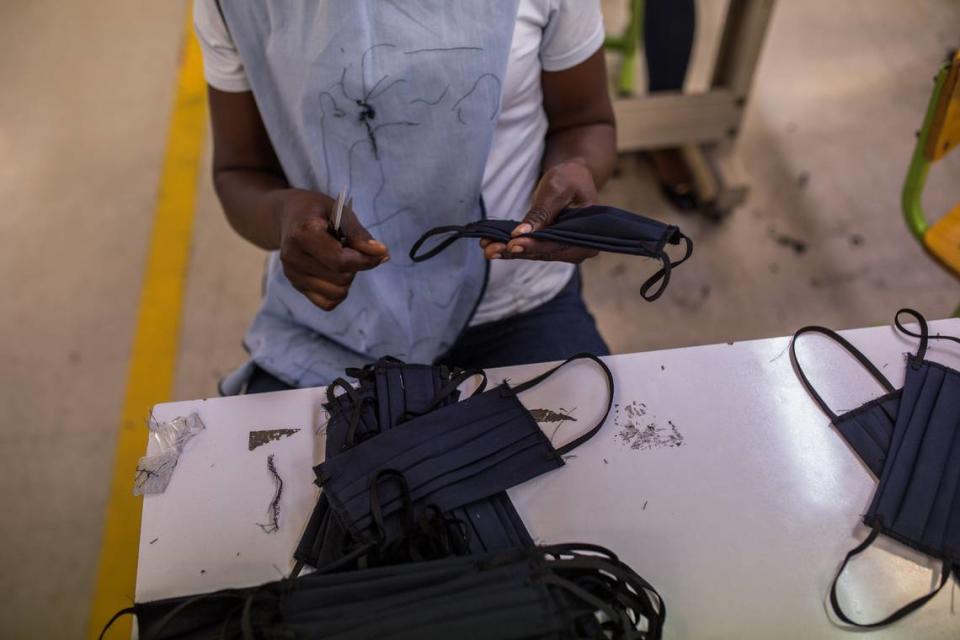

Prime minister orders Haitians to wear masks in public and orders firms to make more masks

Haiti’s prime minister has ordered all Haitians to wear masks in public as of Monday and banned factories from exporting the personal protective gear until they supply the government first.

Haitian Prime Minister Joseph Jouthe, who has struggled to enforce social-distancing measures in the fight against the global coronavirus pandemic, said anyone caught without a mask risks imprisonment because “they are trying to kill themselves.”

“I have a population to protect,” he said, speaking during a morning radio interview Tuesday on Magik 9, a Port-au-Prince radio station owned by the country’s daily newspaper Le Nouvelliste.

But where Haitians — the majority of whom live on less than $2.41 a day — will get masks to comply with the order remains a mystery.

Since last month, the government had been promising to distribute 20 million masks to the population. But Jouthe, blaming the local textile industry for the government’s failure to deliver, admitted that he barely had a fraction of them in his possession for the country’s nearly 12 million inhabitants. As a result, he said, the government is banning factories from exporting masks until they each provide a minimum of 500,000 masks to the government at a cost of 50 cents each.

Jouthe issued the order in a communique on Monday. He later reiterated his position in the radio interview, while accusing factory owners — whom he allowed to reopen last month despite the dangers of the global pandemic — of failing to live up to “a gentleman’s agreement” to produce 20 million masks to be sold to the government at 50 cents a piece.

“We will only give authorization to export if they deliver to us between 500,000 and 1 million. Anyone who fails to hit that number will not get an authorization,” Jouthe said. “I have no choice but to play on two levels: When they sell abroad, it’s good. [But] secondly, I have to take precautions so that I don’t lose the textile industry in Haiti.”

COVID could lead to social unrest and even famine in Haiti, global health experts warn

Jouthe said he was recently approached by the president of the Association of Haitian Industries, Georges Sassine, seeking authorization for some of the country’s factories, which see an opportunity in the hard-to-get personal-protective-equipment arena, to export face masks.

“It’s an aberration,” Jouthe said. “One, you’ve never been able to deliver the masks, those that you promised you would produce. Two, I cannot now give authorization to export masks when that’s not the agreement we had before.”

Still, he acknowledged giving authorization to one company, which he declined to name, to export its masks.

The country currently has 101 registered cases of COVID-19 and 12 deaths.

“I have to find a plan for everyone to find masks for them to wear,” he conceded. “I am confronting an extremely dangerous epidemic.”

In late March, unable to purchase masks after shutting down the country’s textile industry as part of anti-COVID-19 measures, Jouthe authorized the reopening of seven factories, saying they would provide 1 million masks for free to the government.

Three weeks later, despite concerns about the virus further spreading in the workplace, he authorized all factories in Haiti to resume operations at 30%, while not making any provisions to protect workers from infection by avoiding overcrowded public buses.

Jouthe complained that he now had to assign people in his office to call each of the factories to try to negotiate an agreement with them.

Sassine, the president of the textile association, said while the prime minister had raised the matter of the 2 million masks with him, and said the government would “not pay more than 50 cents per mask” — a price well below the cost of production — there exists no formal agreement.

The association, whose members include representatives of the 38 factories in Haiti, can bring everyone together in the same room, Sassine said, but it’s up to the government to negotiate agreements with the individual factories, the majority of which are foreign-owned.

“All of the factories here are being run by employees, they are not the owners,” Sassine said. “They cannot base their decision solely on someone’s word. ... I cannot orally tell a foreign company to do this, or do that. They need something written.”

Sassine said the factories that were allowed to open on the condition that they would donate masks to the government are living up to their promise and are using their own materials to do so.

“We’ve already delivered 704,906 masks by 19 factories and we have all of the receipts,” he said.

With U.S. retailers filing bankruptcies and COVID-19 threatening to undo what’s left of the U.S. retail market, Sassine said it’s imperative that the factories, which mostly export T-shirts to the U.S. market, begin producing to export so they can generate revenue. The factories that donated the free masks to the government — along with 15,000 medical scrubs, bed sheets and even money — all have workers, rent and electricity bills to pay, he said.

“It’s a huge effort,” he said.