Prison building has provided little economic value in Eastern Kentucky, study says

Federal prisons have long been promised as economic boons to Eastern Kentucky communities looking to replace some of the local dollars lost with the continued decline of the coal industry.

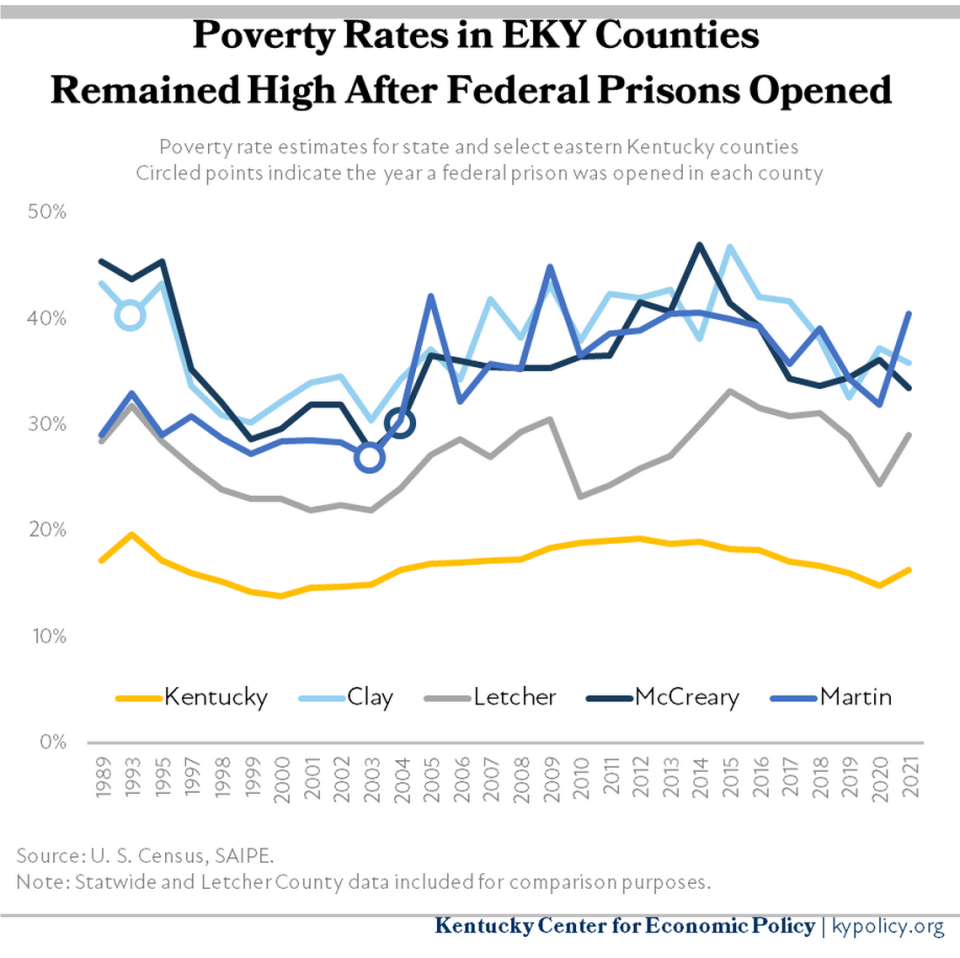

A recent study from Kentucky Center for Economic Policy questions that logic. Using U.S. Census data from the three Eastern Kentucky counties where federal prisons have been built in recent decades, the study concludes the prisons — pitched as job creators for locals— have provided little in the way of economic benefit.

But some local county officials have said they’ve seen some positive economic outcomes from the prisons, including revenue from occupational taxes and some local hiring.

Since 1990, at least seven prisons — a mix of federal, state and privately operated — have opened in Eastern Kentucky. Three of those prisons, located in Clay, Martin and McCreary counties, are federal. There is a fourth federal facility in Boyd County but it opened in 1940.

The study comes months after federal officials revived plans to build a federal prison facility in Letcher County when they announced they were again looking at potential prison locations in the southeastern Kentucky county. A previous years-long plan to build a federal prison there was scrapped in 2019 in the face of local pushback.

Could a new $444 million Kentucky prison get held up by inmates worried about bats, wetlands?

“We wanted to look into what the track record has been, so that folks can make the best decision moving forward about what makes sense,” said Jason Bailey, one of the study’s authors and the executive director of the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

What does the study say?

Three counties with federal prisons — Clay, Martin and McCreary — have all experienced continued population loss since prisons opened in those counties, the study said. The prison in Clay County opened in 1992, while the prisons in Martin and McCreary opened in quick succession in the early 2000s.

The poverty rates in those counties have also remained high. When United States Penitentiary Big Sandy opened in Martin County in 2003, the poverty rate was below 30%. In the two decades since, the county’s poverty rate has spiked above 40% three different times, most recently in 2021.

Over the past three decades, the median household income in all three counties has remained relatively flat. Out of over 3,000 counties nationwide, all three counties rank in the bottom 30 in median household income.

“Since we have two to three decades of experience now with these three federal prisons, we have enough time to understand what the impact is,” Bailey said. “It’s just not able to in any way stem the out migration, the drop in employment, and the ongoing alarmingly high poverty rates and low incomes in Eastern Kentucky.”

What do local officials say?

The high security penitentiary in McCreary County has provided some jobs locally but hasn’t had the “huge economic impact” that was forecast previously, said Jimmie Greene, the county’s judge-executive.

In recent years “quite a bit more local people” have been hired at the prison and the county does get a little under $400,000 annually in occupational tax revenue, Greene estimated.

As far as the county’s median income, Greene said the prison’s population may lower that data point. The U.S. Census counts prison populations within the county where they’re located. In a county of 17,000, a population of 1,500 incarcerated people will “bring down your median income.”

Carolea Mills, the deputy judge-executive in Martin County, told the Herald-Leader the prison there had been an overall positive addition. “A lot more job opportunities” will be open there in the near future as some of the employees of the 20-year-old prison reach retirement, Mills said.

Public officials in Letcher County also praised a potential prison’s economic impact during a public scoping meeting held in the county in November, the Mountain Eagle reported. Terry Adams, the county’s judge-executive, said he supported the prison. Former state Rep. Angie Hatton also said she supported it.

Some local citizens at the meeting asked that the nearly $500 million designated for the prison’s construction be used instead to rebuild housing and infrastructure in the wake of last July’s deadly flooding, a Bureau of Prisons’ summary of the meeting said. Only Congress can redirect those funds, the bureau noted in response.