State prison warden banned braids, cornrows and dreadlocks. A Black inmate is now suing.

The February 2021 prison memo sent by Warden Brad Adams was clear.

“Effective immediately” inmates in the medium-security, all-male prison known as the Northpoint Training Center in central Kentucky, would need to have “searchable hair” if they traveled in or out of the facility – to court, another institution, or to the hospital – or were placed in solitary confinement.

“Braids, corn rolls [sic], dreadlocks etc. are not permitted if they are not searchable,” the memo states. Inmates would be given 30 minutes to remove those hairstyles or it would be cut from their heads and filmed by officials for documentation like any other use of force.

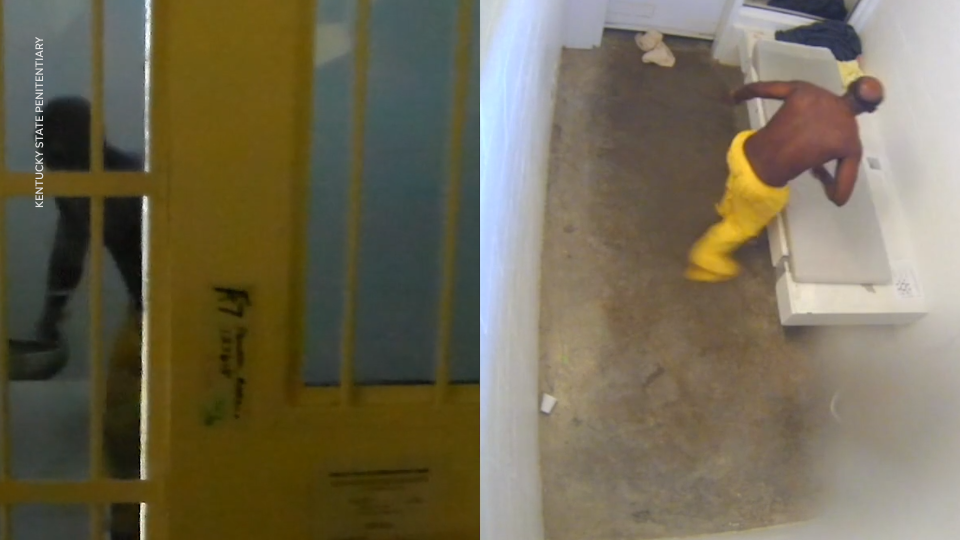

The prison also pulled Black hair-care products from canteen shelves, according to a federal lawsuit filed by the inmate. USA TODAY also reviewed internal prison documentation and video of Thurman's locs being forcibly cut, which were obtained through public records requests.

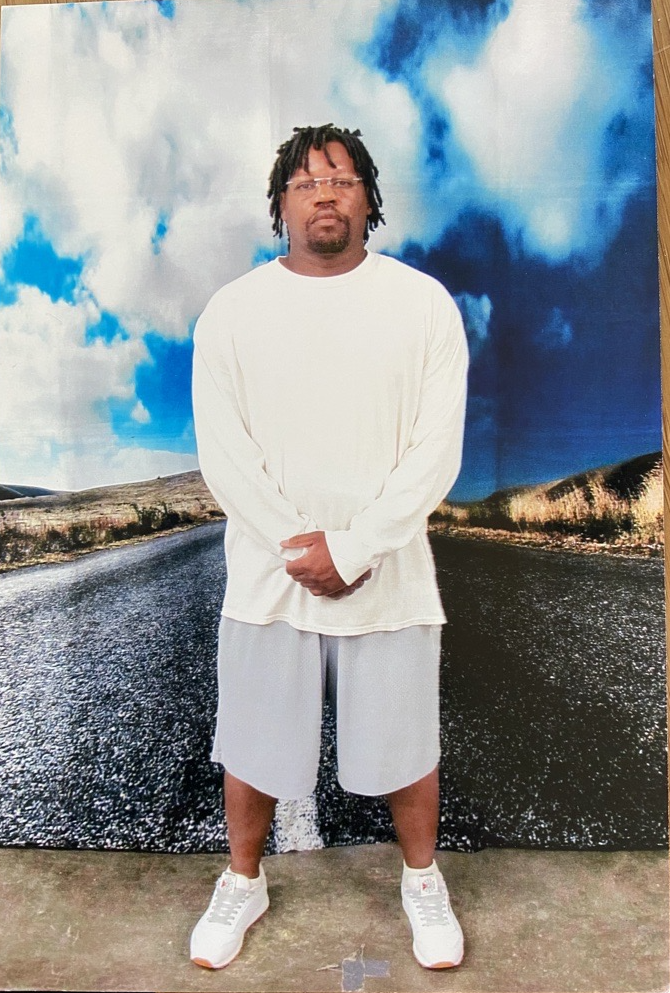

Carlos Thurman, 50, alleges in his federal court complaint against the Kentucky Department of Corrections leadership that his constitutional right to religious liberty and expression as a Rastafarian were infringed upon by the prison’s policy against dreadlocks. In group grievances filed with the prison and letters to Department of Corrections leadership last spring, Thurman argues that he and other Black inmates were being racially discriminated against and their First and Fourteenth Amendment rights violated.

“If a white inmate with long hair down his back gets into a fight with a Black inmate with dreads, cornrows or braids, the white inmate will be allowed to keep his hair,” Thurman wrote in his March 2021 grievance. But “the Black inmate will have to get his hair cut. Where is the fairness?”

The lawsuit comes amid a growing national debate over hair discrimination against Black people. The U.S. Army updated its grooming policy last year to allow for more inclusive hairstyles, California in 2019 became the first state to ban hair discrimination and the U.S. House passed a similar measure in March.

Hair discrimination against Black people is common in the United States with roughly 86% of Black teens saying they experienced hair discrimination by age 12, according to data from the CROWN Coalition, a coalition founded by Dove and the National Urban League, among others, that supports legislation banning hair discrimination.

'How prisons treat Black men differently'

Thurman’s lawsuit argues that he is a practicing Rastafarian who wore his hair in dreadlocks per his beliefs.

In this Kentucky prison: A mentally ill man was pepper-sprayed, choked and hooded before dying

“Even though there is not an explicit racial discrimination claim in the complaint, I firmly believe that what happened to him is part of how prisons treat Black men differently,” said Heather L. Gatnarek, staff attorney with the ACLU of Kentucky Foundation, which is representing Thurman.

Thurman alleges that in retaliation for his filed grievances and appeals, the prison leadership abruptly decided to transfer him to another facility and forced him to cut his locs.

“While my hair was being cut, NTC staff were laughing with each other while staring at me. Even after because of how my hair looked with the dreads cut. This was humiliating to say the least,” Thurman wrote in a letter to Kentucky Department of Corrections Commissioner Cookie Crews.

Despite the fact that “the ‘searchable hair’ policy explicitly references hair being searched, at no point during the transfer process did (prison officials) attempt to search Mr. Thurman’s hair,” the lawsuit states.

His hair was cut and placed in a bag, and transferred with his possessions to the Eastern Kentucky Correctional Center. Again, the lawsuit alleges, “at no time did any prison official or administrator attempt to search the cut dreadlocks that were gathered in a bag and transferred with Mr. Thurman.”

That same day, two other Black men who wore their hair in dreadlocks also had their hair forcibly cut by prison officials without any efforts to search the hair, the suit said. Meanwhile, a white inmate with long hair down to the middle of his back was not forced to cut his hair or searched for contraband.

“A lot of the time you have policies that are facially race neutral – meaning they don’t say anything about race in the language of the policy – those policies can nevertheless be discriminatory against Black people who are wearing natural hairstyles or protective hairstyles intimately connected with the Black identity,” said Michaele N. Turnage Young, senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

In an email, Kentucky Department of Corrections spokesperson Katherine Williams said the department’s search policy “applies to all inmates regardless of race or gender” and that the department is in the process of reviewing and refining it.

That policy, reviewed by USA TODAY, makes no mention of braids, corn rows or locs, and states that an inmate may choose the length of his hair, and wear a mustache, beard or both. There is no reference to hair needing to be searchable.

Williams said by email that the memo at Northpoint regarding searchable hair was issued by the facility’s former warden and is no longer in effect at the prison. She added that “it does appear that some other facilities also had this requirement regarding dreadlocks,” but did not specify how many or who put those requirements in place.

“This requirement is no longer in effect at any facility,” Williams said, declining to comment further on the memo because of ongoing legal proceedings.

Thurman, who was convicted by a jury in 1994 of theft, unlawful imprisonment and murder, was sentenced to 109 years in prison.

17 states have banned hair discrimination

There's evidence that policing of Black hairstyles has been in effect for years in other state correctional facilities. For example, in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, a pretrial detainee who is Black and a practicing Rastafarian was put in solitary confinement for more than a year because he refused to cut off his dreadlocks. The jail policy prohibited braids, cornrows and dreadlocks but allowed other kinds of long hair.

The detainee, Eric McGill, Jr. and two other Black men, filed suit in 2020, and earlier this year the county agreed to change its policy – no longer prohibiting such hairstyles, regardless of religious beliefs – and paid $147,000

The CROWN Act has been enacted into law in at least 17 states, according to the coalition, but it’s not law across the United States so it “presents an uneven landscape when it comes to whether your right to wear your hair the way it grows out of your head is protected,” Turnage Young said.

She said schools and other facilities have policies that don’t allow children to have beads in their hair, a policy that primarily impacts Black girls.

”They’re the only kids where they’re saying you can’t have it. That is discriminatory,” Turnage Young said.

These policies around grooming often fail to account for the fact that not everyone can easily achieve the same hairstyles without adverse effects. That was one of the reasons the U.S. Army updated its grooming policy.

“It’s problematic, it’s discriminatory, and it really shouldn’t be the case that we’re having policies that are forcing people to take costly, time-consuming and damaging measures to make them conform to a rule that basically didn’t have them in mind in the first place,” Turnage Young said.

The Kentucky state prison system has upped its use of technology to search inmates for contraband, including with full-body scanners at every prison, Williams said in an earlier email. She said the department does not allow retaliatory actions to be taken against inmates for filing grievances.

Adams, the former Northpoint warden, did not immediately respond to emailed requests for comment.

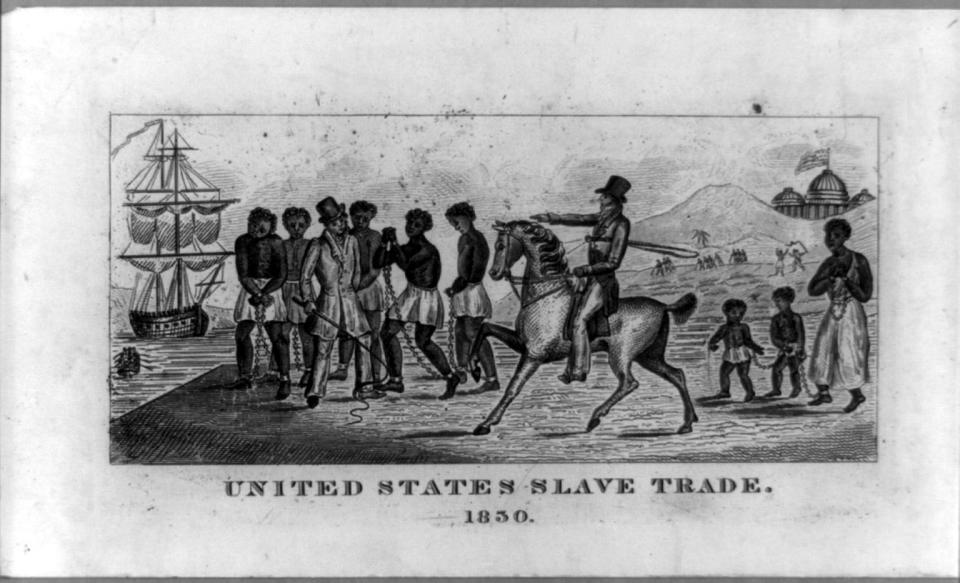

One of the earliest attempts at controlling African American hair was in the slave trade, said Alesha Hamilton, an associate attorney in the Cincinnati office of Frost Brown Todd, LCC who has researched the issue. She said one of the first thing slave traders would do when slaves boarded or exited their ships was cut their hair.

“It was a sign of control and conformity,” Hamilton said.

She said a federal law would essentially place hair discrimination under the umbrella of racial discrimination, specifically preventing discrimination against natural or protective hairstyles.

Jennifer Bourgeois, a research fellow at the Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University, said she was not shocked by the fact that this was happening in Kentucky prisons.

“These individuals are already being double criminalized,” Bourgeois said. “Now they’re being punished again while they’re incarcerated for their hair.”

She noted that while incarcerated people lose certain types of rights, such as around the Fourth Amendment’s protections from unreasonable search and seizure, prison officials seemed to be “hiding behind some of the Constitutional rights that are taken away” to essentially target Black hair.

Bourgeois said especially during hot summer months, protective hairstyles like braids can be one less thing to worry about – even more so in a prison setting. When going through airport security, one of the few places where most free Americans lose certain rights, she has sometimes been asked to take down her hair if her long braids are in a high bun, so that it can be easily searched. But typically people of color or those with cultural awareness have been more sensitive and appropriate in how they approach such a thing.

“It goes back to cultural awareness and with lots of different hairstyles, the braids, the locs, you can still get access to our scalp,” said Bourgeois, who recommended cultural awareness training for those in power in a Brookings report last year.

“If it’s happening out in the free world, it’s not surprising it’s happening in carceral settings as well, it’s just another way of policing Black bodies,” she said.

Tami Abdollah is a USA TODAY national correspondent covering inequities in the criminal justice system. Send tips via direct message @latams or email tami(at)usatoday.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hair discrimination in prison? Black man was forced to cut dreadlocks