Prison, jail education programs help incarcerated youths, adults change trajectory

The brilliant physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton likely never contemplated that his first law of motion would help frame a conversation about the importance of educating men and women incarcerated in jails or prisons.

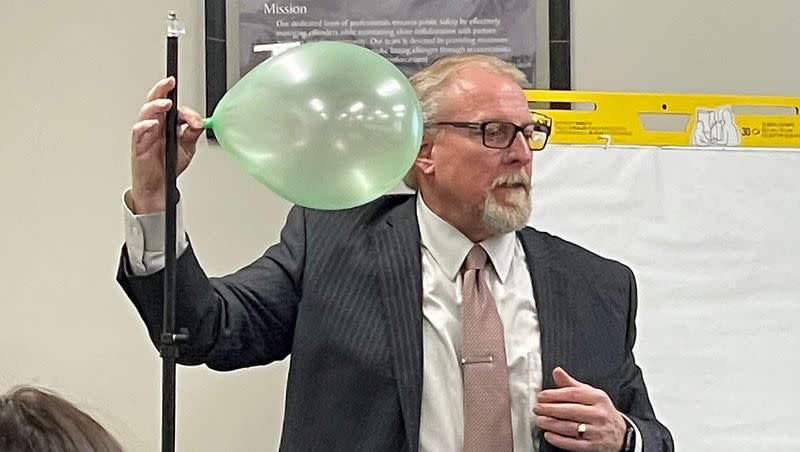

To demonstrate the point, Dennis Walker, training coordinator for the Utah Department of Corrections, gently kicked a small soccer ball down an aisle between tables in a classroom during the Utah Corrections Education Summit on Friday.

Newton’s first law of motion says, “Every object in a state of uniform motion will remain in that state of motion unless an external force acts on it.”

At first, the ball traveled unimpeded. Then, a participant, instructed by Walker, redirected the ball with his kick.

“Imagine yourself in somebody’s life and having that power. I know it’s physics and it’s science and I’m a nerd but this applies to life,” Walker said, addressing educators and administrators who work with incarcerated adults or youth.

“The theory behind this is the opportunity to intervene and change trajectory.”

Walker, who is in his mid-60s and earning a doctorate degree in education, knows the power of one person changing the trajectory of another person’s life, because it happened to him.

He grew up in the Los Angeles area and dropped out of school in the 10th grade. The schools were overcrowded and teachers were overworked, so struggling students could slip through the cracks.

Walker said he had learning disabilities and a speech impediment, and he was functionally illiterate.

He rode and hung out with a biker gang. “Everyone I hung with, everyone I rode with, they are dead. I used to say they are in prison or dead but now they are dead,” he said.

Walker’s life took a different path when he met a woman who later became his wife, who recognized he was functionally illiterate and helped him develop strategies to overcome his challenges. Walker had served in the military and had a GED but until he learned to read effectively, he was stuck.

When he did learn to read, Walker said he was angered that he only then could do what others around him could do with seemingly little effort. He immersed himself in reading and learning.

Walker said his wife “tricked” him into going to college. She asked him if she could get him accepted into the University of Utah, whether he’d be willing to go. He scoffed but agreed to go if he was admitted.

A while later, she handed him a class schedule and he honored his agreement to go to college. He immersed himself in his studies, working hard to complete assignments and attend his classes.

What he didn’t know was that she had signed him up for community education classes that were open to anyone. But it lit a fire for learning and set him up for success as he earned a bachelor degree in psychology from the U. and later, a master’s degree from Utah Valley University, graduating with honors.

People drop out of high school for many reasons, he said. It creates a gulf between those who graduated and those who didn’t. The former can check the box on a job application, the latter cannot.

“They (graduates) all move into this other realm of high school graduates and they move on,” while people who don’t graduate don’t talk about it, he said during an interview at the Fred F. House Training Academy.

They develop strategies to “bury that or say, ‘It doesn’t matter. It’s never going to matter.’ They discount the value of that,” he said.

But it does matter. Witness the people who earn their high school diplomas or higher education certificates or degrees while incarcerated, he said.

“We say, even just a high school degree? It’s huge. Or a GED? That high school degree means that I have performed academically at the same level as everyone else. It normalizes you as a human being. That’s powerful,” he said.

Related

It comes back to momentum and trajectories, Walker said.

Experiencing success in education “opens opportunities and can change the trajectory of someone’s life and open up multiple opportunities and they gain momentum. That velocity is you go from one success and you look for the next opportunity to feel that,” he said.

The day anyone dons a cap and gown and “you toss the tassel, if you’re 17 years old, or you’re 48 or 60, that is a defining moment. It opens up a new opportunity for you to see who you are.”

On average, a person who participates in postsecondary education while incarcerated is approximately 45% less likely to commit an offense that returns them to prison, according to conference materials.

The more education incarcerated individuals complete, the less likely they are to return to prison.