Private planes, private plans fall short in a public health emergency

The white Beechcraft Baron twin-propeller plane left Baltimore Washington International Airport a few minutes after midnight, achieved cruising altitude, then flew north at 180 miles an hour. At 1 a.m. on Jan. 27, 2022, it dropped its wheels and landed at Teterboro Airport in New Jersey, where the air was 18 degrees. To the east, the clear white lights of Manhattan’s skyscrapers lined the horizon.

Quest Diagnostics owns Quest Air, a private cargo airline with 26 planes. The fleet includes propellers and jets, many branded with the company’s name and bright green logo. The Beechcraft’s livery is more discrete, with white paint and maroon racing stripes, giving no indication of its purpose. The flight was tracked by publicly available aviation websites, and no outsiders witnessed its arrival.

It’s impossible to know for certain, but the plane probably was delivering samples to Quest’s newest laboratory, located eight miles from the airport in Clifton, New Jersey. The Quest logistics empire centers on five mega-labs situated around the country. The one in New Jersey is the newest and biggest.

This is what “efficiencies of scale” look like.

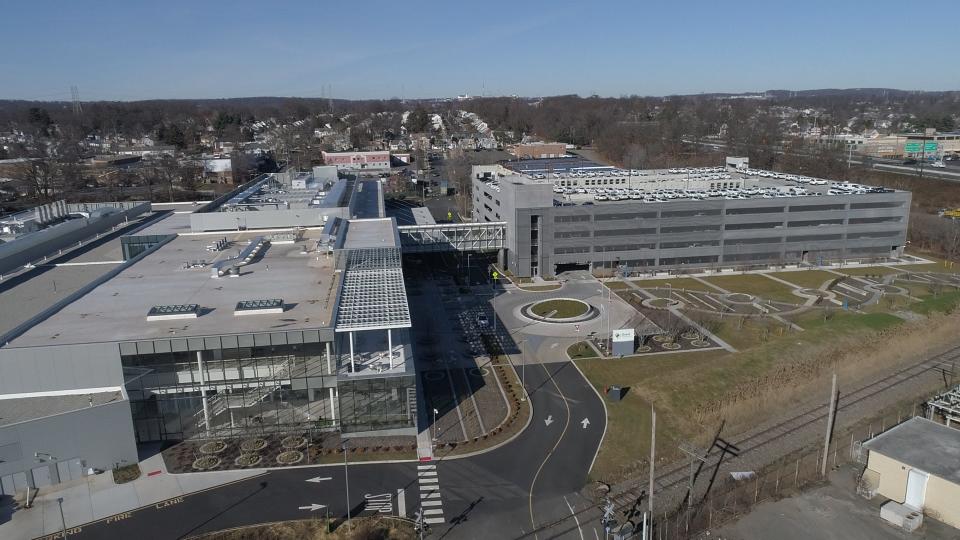

Opened in January 2021, it resembles an Ikea without the furniture. It sprawls across 250,000 square feet and cost $250 million to build, said Bob Roggeman, the Quest manager in charge of construction.

During a recent tour, Roggeman pointed to a row of silver doors along the north wall of the facility’s biggest lab. Each door is a refrigerator that can hold 330,000 test tubes of blood.

The last time Quest opened a mega-lab, in Marlboro, Massachusetts, in 2014, the company christened it the “lab of the future.” It can handle 60,000 test orders from doctors a night. This new laboratory in New Jersey is built to handle 140,000 orders a night, Roggeman said. Fully built out, the site will test 40 million people a year across seven states.

“This is the largest lab within Quest. By far the largest,” Roggeman said. “When you look at the industry, there’s continuing pressure to drive costs down. One of the ways you drive costs down is you consolidate. You maximize your assets, get your highest productivities and efficiencies.”

In an article for The New Yorker magazine, Atul Gawande, a surgeon and public health researcher at Harvard Medical School, wrote that Quest and Labcorp can be properly understood as “really logistics and distribution companies wrapped around a network of regional laboratories.”

The lab giants operate two of most sophisticated — and secretive — logistics networks in the United States.

“It’s very much a black box,” said A. Jay Holmgren of the University of California, San Francisco. “Academics find it’s hard to dig into that data because Quest and Labcorp have been less of a partner. Because it’s such a duopoly of two companies, they just do their thing.”

Quest has done everything possible to make its new facility disaster proof. For redundancy, the laboratory has two automated assembly lines to move samples through the machines, Roggeman said. The facility is connected to two separate fiber optic networks, plus a backup power plant should it lose electricity. Quest has contingency plans to house essential workers at nearby hotels before major storms.

Yet the lab is so big, its very vastness places testing across the entire Northeast in danger.

“We’ve got to stay in operation. If something happens to this facility and we couldn’t operate, there is nowhere to send that work,” Roggeman said. “Because nobody else has the magnitude of operations to support that volume.”

During the tour, Roggeman walked a delicate balance. He was charming, enthusiastic, and deservedly proud of the capable facility he’s built. He also was charged with keeping its secrets. Outsiders like journalists are invited inside to look around. But no pictures are allowed of the testing floor. For Quest and Labcorp, the number of machines they own, and the types of machines they operate, is proprietary information. Not even the federal government knows the mix. In normal times, that’s not a problem.

But in an emergency, when every available machine must run at maximum capacity, such opacity makes it impossible for the government to direct samples, testing machines and supplies where they’re needed most.

“There’s no ability in a public health crisis to break those prearranged pathways and shift demand where the supply is," said Scott Gottlieb, former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration. He cited the example of CityMD, a popular chain of walk-in health clinics in the New York City area.

"If CityMD sends all its samples to Quest, and Quest gets overloaded, there’s nothing that anyone can do," Gottlieb said. "You’re just gonna wait."

Testing machines made by different manufacturers present the same problem as electronic health record systems at different hospitals: They can’t talk to one another.

PCR machines give results in terms of “cycle threshold” or “CT value,” which counts the number of times a genetic sequence is copied. CT values matter because they show how much virus is present in a sample. A low CT means a patient is highly infectious, while a high CT means the person probably is not infectious at all.

A problem, said Mara Aspinall, a former laboratory executive who now advises the Rockefeller Foundation, is that each PCR test is different. Each decides the result by looking for different segments of the virus genome. Each chooses a different CT value to decide whether a sample is positive or negative. Even when two instruments from two different companies multiply the same genetic code an identical number of times, each machine gives different CT values for the same quantity of detected virus, sometimes by an order of magnitude, Aspinall said. In other cases, wildly different CT values may actually be identical in terms of infectiousness.

And because these differences are regarded as proprietary, there’s no easy way to translate between them.

“There’s no secret decoder ring,” Aspinall said. “And it is a secret.”

In many ways, Quest Diagnostics and Labcorp have accomplished the goals of their founders. They are huge. And they make lots of money. In 2021 the companies together earned $26.9 billion in revenue. That’s four times larger than the revenue of their seven largest competitors combined.

That size and scale comes with a cost, medical professionals say. Dozens of doctors and laboratory leaders interviewed for this story complained about how difficult it is to engage with Quest or Labcorp. Most did not want their names attached to this story, because they said they fear the duopoly’s power. When doctors and hospitals need answers to simple questions, like the chemical composition of patients’ blood, Labcorp and Quest do a phenomenal job, industry insiders agree, delivering huge volumes of test results quickly.

But when the duopoly’s systems fail — when providers need additional details about test results to inform their diagnoses, when Quest and Labcorp’s computers lose connection with hospital networks, or when testing platforms built for maximum profit and run with little excess capacity receive a spike in test requests — Quest and Labcorp’s highly automated systems often fall behind, experts said. There simply aren’t enough humans or machines available to respond to the unexpected.

“We can’t compete on price,” said Jay Weiss of Allermetrix. “When we do compete head to head with either Labcorp or Quest, it’s easy to win that business because our turnaround times are faster, the results are better, the physicians much prefer our customer service. I guess their strategy is to be the only provider.”

And when it comes to fast computers, fast logistics and fast service to doctors — the trifecta that built the Blood Brothers’ power — doctors complain that in many cases the great silos of diagnostic testing can no longer perform.

Mark Brown would like to hire Quest Diagnostics for some of his testing. But first he must establish a secure data connection between his office and Quest’s computers. This might seem important to Quest, since it involves the son of its founder trying to pay the company money.

Apparently it’s not so important. After six months of phone calls and emails, Brown said, Quest failed to make the connection.

“I can’t get Quest to do their part. I don’t know why,” Brown said. “I just emailed them again last week and said, ‘Holy crap, I don’t know how you guys are in business still. You guys have made a wrong turn.’ I really think my father would be disappointed.”

The pandemic arrives: An empty shell

Here, then, was the state of diagnostic testing on Dec. 31, 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic began. From the outside, America seemed prepared. Academic medical centers had the experts and technology to innovate powerful new tests in days. Labcorp and Quest Diagnostics possessed some of the largest testing laboratories in the world, connected to doctors and hospitals by high-speed computers and logistics.

But Congress, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and people inside the industry understood this facade was fragile.

Quest and Labcorp equipped their labs for maximum efficiency during normal times, with no excess capacity for emergencies. Samples, patient data, billing, and test results traveled along hardened pathways that were costly to build, slow to change, and impossible to escape. Data connections within health care silos were glitchy. Between silos, they didn’t exist.

Officially, the responsibility of responding to pandemics and other emergencies falls to local, state, tribal, and federal public health agencies, including the CDC. In actuality, none of those public agencies has received anything close to the billions of dollars a year in funding required to build and maintain the reserve of test machines, or the billing and logistics networks needed to run them, all of which must be in place before a pandemic starts to handle the surge in test demand, said former FDA chief Gottlieb and Scott Becker of the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

Even in slow times, public agencies weren’t even in the game. Chronic underfunding left them no systems to perform diagnostic testing at modern speeds. No disease surveillance in real time. No data connections with hospitals or each other.

“Public health labs are not built for mass testing,” Becker said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Quest Air helps Quest Diagnostics meet COVID testing needs