Pro athletes compartmentalize emotions. That doesn’t mean returning to the field after Hamlin’s collapse will be easy.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In a high-impact sport like football, injuries are common. But rarely has there been a medical episode as harrowing as Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin’s collapse from cardiac arrest during a game this week, which is certain to be on NFL players’ minds as they take the field this weekend.

“It’s scary,” D’Andre Swift, a Detroit Lions running back, told reporters in a locker room interview. “We see injuries week in and week out, but something like that, you’re talking life-and-death situations. It kind of hit a little different.”

To play professionally, athletes must be highly skilled physically as well as mentally, sports psychologists say. They need to be able to compartmentalize their emotions — whether it’s nerves on the Olympic stage or stressors in their personal lives — so they can focus on their sport.

Some NFL players say they are struggling to do that after Hamlin’s collapse on Monday night.

Calais Campbell, a defensive end for the Baltimore Ravens, told The New York Times that the hit Hamlin took prior to his heart stopping made him question whether football is worth the risk.

“I keep thinking that I’ve tackled like that hundreds of times and I’ve been fine. But what if I’m not fine the next time?” Campbell said Wednesday.

While doctors have not disclosed precisely what happened to Hamlin, it is believed he experienced a rare phenomenon called commotio cordis, in which a blunt force hits the chest at a very specific window in a heartbeat’s cycle, knocking it out of rhythm. While the condition can be deadly, the Buffalo Bills reported Thursday that Hamlin was showing “remarkable” improvement and appeared to be “neurologically intact.”

That commotio cordis is so uncommon should be a comfort to NFL players, said John Heil, a clinical and sports psychologist in Roanoke, Virginia.

Still, he added, just because it was rare doesn’t mean athletes will feel reassured.

“That’s a good logical argument, but logical arguments don’t always win out over emotion,” he said.

Heil said it’s critical that players seek support so they can process how they’re feeling — not just so they can play well but, more importantly, for their safety. In the 1980s, he was studying injuries on a football team at the University of Utah when one player suddenly died of a heart condition. The week after, there was a spike in injuries among the player’s grieving teammates, Heil said.

Yet asking for support is not always easy.

“The thing that we’re kind of taught to do in this sport, because it’s such a ‘manly’ sport, is to hide your feelings, hide your emotions,” Los Angeles Rams linebacker Bobby Wagner told reporters Wednesday.

“I think that’s a myth,” he said. “Talking about your feelings and talking about things that affect you mentally, physically, are more manly than anything because it takes a lot of courage to talk about those things.”

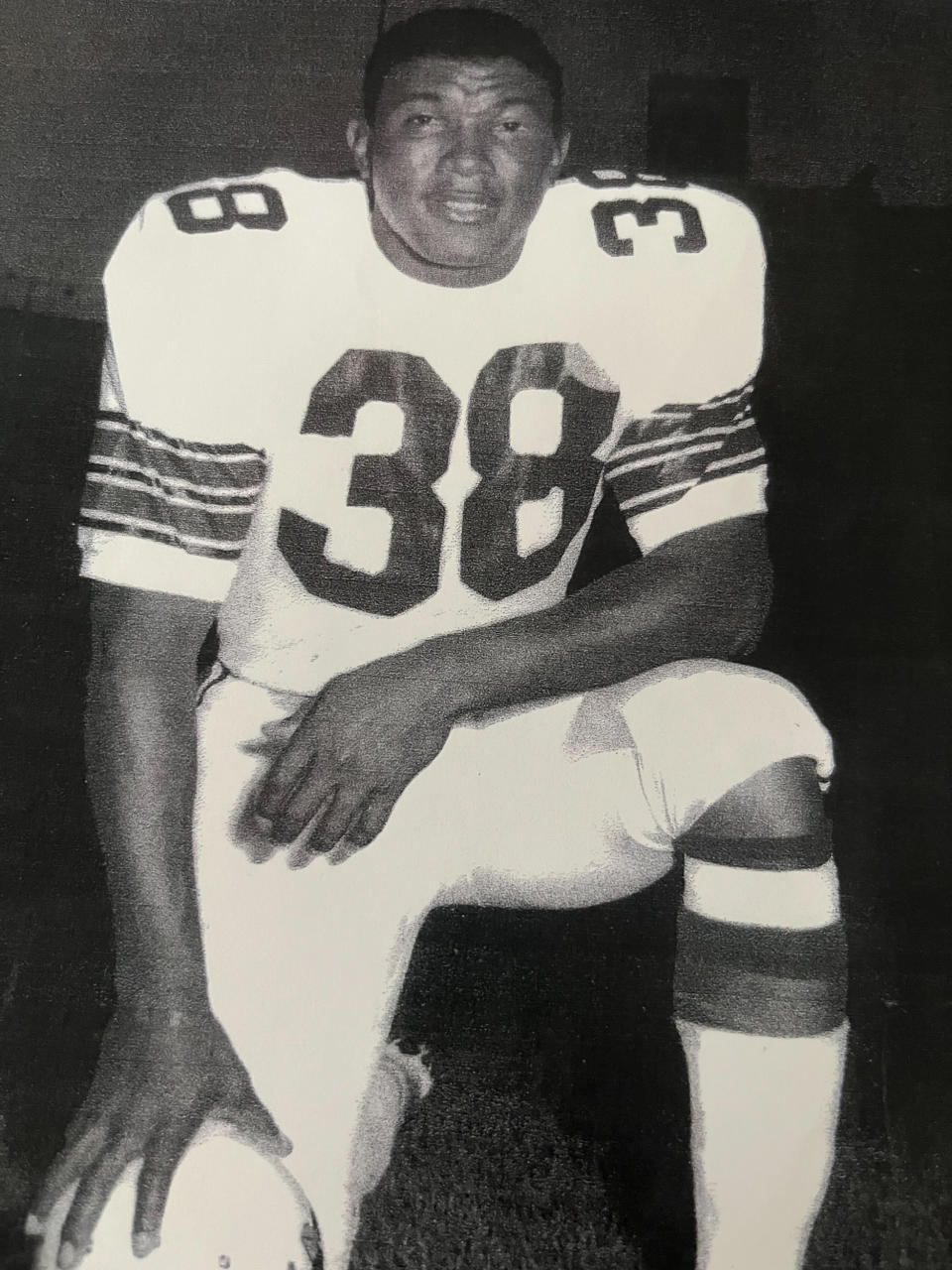

Still, football culture has become more sensitive over the years to the mental health needs of its players, said Bill Triplett, 82, a 10-year NFL veteran.

In 1971, Triplett was a running back with the Detroit Lions when his close friend and teammate, Chuck Hughes, died of a heart condition, making Hughes the only NFL player to die on the field during a game. There were 62 seconds left in the game when Hughes fell facedown to the ground, clutching his chest. After an ambulance raced him off the field, the game resumed before a shocked crowd.

“That was the given,” Triplett said.

He said he ended his football career within a year of Hughes’ death and could relate to players now who are questioning football’s risks.

“It was such a shock to me,” Triplett said of Hughes’ death. “I quickly decided it wasn’t worth it.”

A built-in support system — if players choose to use it

While elite athletes possess excellent mental performance skills that help them push away distractions, they often are not taught what to do with their emotions once the competition is over.

“They’ve been told throughout their lives, ‘Compartmentalize. When you put the helmet on, when you cross the line, everything else in your life goes away,’” said Mark Aoyagi, who has provided sports psychology services to NFL players and is co-director of sport and performance psychology at the University of Denver. “When I walk back off the field, how do I pick that stuff up and deal with it?”

Aoyagi advises athletes to identify what they are feeling and recognize the intensity of the emotion. He also encourages conversations with teammates, who can provide built-in support systems if athletes open up to one another, whether it’s through a conversation with the entire team or in smaller groups.

Every NFL player has a different range of past experiences and coping mechanisms that will affect how they feel about their next game after what happened to Hamlin, the experts said. Once they step out onto the field, they may find their ability to play is as strong as ever.

“One of the benefits of a fast-moving game is it tends to pull your attention in,” Heil said. “It’s just a matter of jumping in.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com