Probe of Jackson’s suspended heart transplant program expands; top surgeon can’t see patients

It calls itself one of the “world’s premier transplant centers” but the Miami Transplant Institute, a crown jewel of the Jackson Health System, has a heart problem.

The institute’s adult heart transplant program was suspended in mid-March at the urging of the network that controls the nation’s supply of organs for transplant.

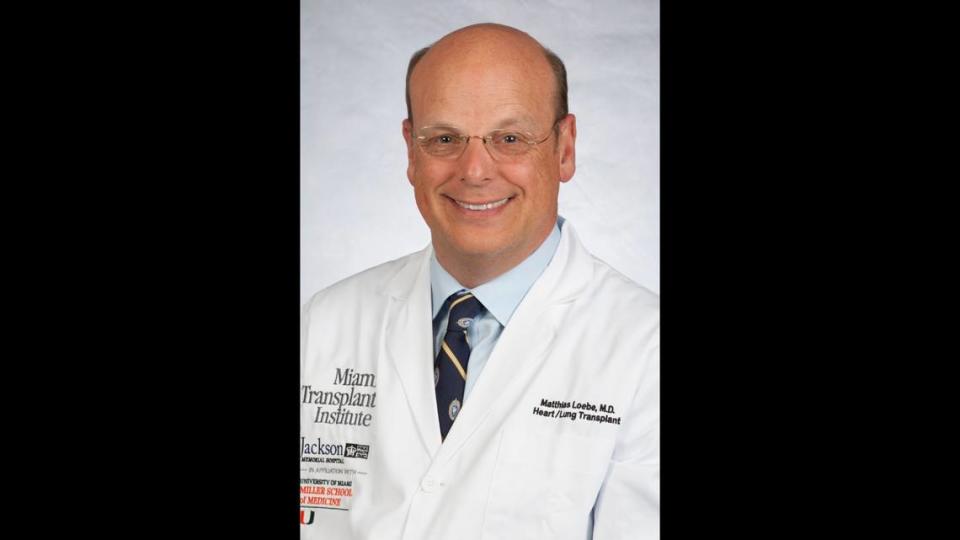

It was only the latest jolt for the heart program. In October, its chief, Dr. Matthias Loebe, was stripped of his administrative duties, although he was allowed to remain in the position through the end of February. That followed the exit of his heart transplant partner, whose departure Jackson declined to explain.

And just this past week, Jackson confirmed a tip that Loebe, 64, faced a new restriction: He will no longer be allowed to treat patients. No explanation was given for that.

None of these setbacks had been revealed to the public, including issues raised with regulators about a separate procedure, which involves implanting of LVADs — short for Left Ventricular Assist Device. It’s basically a mechanical heart pump implanted when a heart is too weak to circulate blood around the body.

Requests by the Miami Herald for a key document detailing the precise concerns expressed by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the agency that urged suspension of the heart transplant program, have been denied by Jackson, saying it is not a public record.

It is unclear whether Jackson’s overall transplant staff, consisting of at least 65 University of Miami doctors handling a variety of organs under an operating agreement with Jackson, informed patients of the series of concerns.

When asked to address that issue of disclosure, a Jackson spokesperson said: “None of our patients had a lapse in their individualized care plan or treatment because of personnel changes.”

2 weeks, 3 agencies

Within two weeks, three agencies embarked on an investigation of the Miami Transplant Institute’s heart program. In the first week of April, the organ sharing network had a peer group team on site. The following week, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the state’s Agency for Health Care Administration, which regulates hospitals, carried out inspections.

In a complaint reviewed by the Herald and submitted to the Medicare and Medicaid agency, Jackson whistleblowers cited “poor patient outcomes,” including deaths that might have been prevented.

Jackson’s performance numbers for heart pump implants trail nationwide trends by a few percentage points.

Example: Jackson reports that 79% of heart pump recipients in the time window 2020 to 2023 survived one year after the procedure. In their complaint to Medicare and Medicaid, the whistleblowers provided a slightly different number: 75%.

Either figure would fall below the national number for 2017 through 2021, the latest data available, during which the one-year survival rate was 83%, according to a 2022 report by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The complaint sent to the federal agency asserted that Jackson deaths after the heart implant were caused by a variety of factors, including prolonged reliance on a ventilator post surgery, persistent organ failure, sepsis and poor surgical management.

The widening probes come on top of the separate inquiry by the United Network for Organ Sharing, known as UNOS, which controls the distribution of donated organs in the United States.

In March, the Jackson whistleblowers sent a list of complaints about the Miami Heart Transplant/Jackson heart transplant program to the private, nonprofit organ sharing network, highlighting concerns about multiple deaths and other troubling issues. That stirred the organ group to alert the Miami Transplant Institute by letter that it was opening an investigation.

The suspension of the heart program that followed was a rare move among transplant centers. In April, the organ network sent the peer-review team, consisting of transplant experts, administrators and regulators, to question doctors and other personnel at Jackson’s transplant institute.

Now, the multiple probes by the organ network and the federal and state agencies raise the issue of when Jackson’s program can reopen.

When asked in late March about the temporary closure of the adult heart transplant program, Jackson officials and UM doctors initially said it was a voluntary decision, but later acknowledged that pressure from the organ network was the primary reason. When asked by public record request to share the letter from the organ network that triggered the program’s abrupt shutdown, Jackson officials refused to do so.

Jackson’s response

Jackson issued a statement this past week to the Herald about the complaints from an unknown number of medical professionals, as well as the investigations that have resulted.

“Jackson Health System takes any allegations and complaints extremely seriously. In this case, our Risk Department investigated these claims thoroughly, and determined them to be completely unfounded, after conducting exhaustive reviews of patients’ medical records.

“While the outcomes in these programs are generally aligned with other national programs, Miami Transplant Institute (MTI) holds itself to a high standard, and believes there is room to improve our heart transplant and [heart pump] programs.

“As we have mentioned before, MTI is currently in a transition that will elevate the leadership, processes, and other elements of the [heart] program,” the statement said. “Through the years, MTI has been one of the top centers in the nation to perform solid organ transplants in adults and children, and our mission remains the same — to save lives and make lifesaving transplants available to the most critically ill patients, even if other hospitals have deemed their cases as hopeless.”

Hearts are just one of several organs transplanted at Jackson, along with lungs, livers, kidneys, the pancreas and intestines. But it is a marquee segment of the transplant facility. Its troubles went undisclosed until the Herald reported on a March 20 meeting in which Luke Preczewski, a vice president at the institute, told staffers about the suspension. In the Zoom call, he said the shutdown would not be announced; the Herald learned about it independently and wrote a story the next day.

The whistleblowers, while reaching out to various agencies to express their concerns, have chosen to remain anonymous, making it difficult to determine how many they represent and whether there could be multiple groups lodging complaints. In any event, government investigators are taking the matter seriously. In the case of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the complaint generated a response in minutes from a top physician with the federal agency.

The current investigations and the news coverage have dealt a blow to the image of Jackson. Miami-Dade County’s taxpayer-subsidized hospital network spent about $2.7 billion last year. It is supported, in part, by a $386 million subsidy generated by a half-cent sales tax and an additional $238 million from Miami-Dade County funding. That accounts for a quarter of Jackson Health System’s spending plan.

Marcos Lapciuc, a businessman who served on Jackson’s governing board, the Public Health Trust, said Jackson executives and UM’s doctors have a responsibility to inform the community about the heart transplant program’s problems — within certain limits.

“Jackson is a publicly owned hospital and healthcare system, so within parameters it needs to give an accounting to the Miami-Dade County Commission and the community about what’s going on,” said Lapciuc, who was a trust member from 2007 to 2015 and served as chair of its financial recovery board during a dire period.

“In a perfect world, they have to be transparent, but it’s important to know there can be valid considerations for taking a cautious approach,” Lapciuc said, citing concerns about potential litigation and the privacy of patients.

The personnel shake-up at Jackson’s heart transplant program comes as the Richmond, Virginia-based organ network chartered by Congress in 1984 and funded by federal dollars to maintain a national registry for organ matching, is expected to issue an “action plan” at the end of April that will prescribe what Jackson’s heart transplant program must resolve to reopen.

Jackson officials won’t comment on that process, including the team of peer-review medical and administrative experts who visited the Miami Transplant Institute nearly three weeks ago.

The hairdresser’s ordeal

According to Jackson whistleblowers, the organ network’s peer-review team is focusing on patient outcomes, including at least five heart transplant patients who died in recent years when Loebe was at the helm of the program. Among them: Frank Ricigliano, 56, a Miami hairdresser who underwent heart transplant surgery at the Miami Transplant Institute in 2021 and died less than three months later at Jackson.

His feet turned black, “just like you would see someone who had been dead for several years like a mummy,” said Ricigliano’s partner, Chuck Ellis. So did his hands. Splotches of black covered his body.

“He got gangrene in his left foot, his right toes were going to have to be amputated, his fingers on both hands were going to have to be amputated. They had turned black and were literally falling off,” said Michael Hamilton, Ricigliano’s roommate and healthcare surrogate.

Ricigliano’s surgeon was Loebe.

READ MORE: He died after getting a heart transplant at Jackson. His loved ones want answers

No more patient contact

Loebe was recruited to Miami from the Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center to head the heart transplant program in 2015. The DeBakey Center declined to release Loebe’s personnel file to the Herald, saying it is a private facility and not subject to public records requests.

In March, Jackson officials told the Herald that Loebe had been notified five months earlier by the transplant Institute’s executive director, Dr. Rodrigo Vianna, that he would be replaced as chief of the heart transplant and heart pump programs, effective at the end of February. He was told he would remain in his job until his successor could be hired. As part of his change in duties, Loebe’s salary was to be cut by $150,000, effective Feb. 28, the Oct. 13, 2022, letter from Vianna to Loebe said.

Loebe told the Herald that he did not see this personnel change as a demotion. Rather, he was simply trying to lighten his workload as Jackson’s principal heart transplant surgeon. He also said the peer review, focusing on patients’ deaths, organ matches and infections, would lead to a better heart transplant program.

That was before the hospital took the latest action last week.

“Dr. Matthias Loebe is no longer treating patients at Jackson Health System,” a Jackson spokesperson told the Herald, declining to elaborate. “Jackson has ample coverage with other heart transplant surgeons.”

Since that statement was issued, Loebe has not responded to inquiries from the Herald..

READ MORE: This heart pump can be a better option than a transplant. But it’s not for everyone

A venerable institution

The Miami Transplant Institute, founded in 1970, is one of the oldest in the country. In 2019, physicians there performed 747 transplants of all kinds, the most in the country, according to publicly available organ data. Most of those involved kidneys and livers.

The institute started performing heart transplants in 1986 and has done 786 of the procedures since 1988, when the organ and transplantation network began tracking transplants, through March 2023. Of those, 697 were in adults.

The institute has seen a decrease in heart transplants over the past several years, partly due to more patients receiving the mechanical heart pump. In the past, the pumps were mainly used to keep patients alive while they waited for a transplant. Now, rather than serve as a bridge to a transplant, the devices sometimes replace the need for a transplant, Dr. Chris Ghaemmaghami, executive vice president at Jackson Health, told the Herald. He’s also the chief physician executive and chief clinical officer at Jackson.

According to medical experts, the average cost of a heart pump implant is $175,420.

Jackson officials confirmed that regulators with the federal and state agencies made unannounced visits to the Miami Transplant Institute two weeks ago. The teams zeroed in on heart transplant services as well as the pump implant program, Jackson officials said.

Jackson officials said that while the adult heart transplant program is now closed to 15 patients on a waiting list, it is still active for one already hospitalized patient who is awaiting a transplant. They also said the pump implant program, though under scrutiny at both the state and federal level, is still operating. Unlike the nation’s organ transplant programs, which are overseen by the United Network for Organ Sharing, there is no one outside body that monitors pump implants.

‘Could have been prevented’

Since 2020, Jackson said, 89 patients have undergone the heart pump procedure at the institute, and 19 of those recipients died within one year. The complaint to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which was reviewed along with other documents by the Herald, offered slightly different numbers for that time period: 84 heart pump procedures and 21 deaths.

The complaint by the whistleblowers claims that many of the deaths “could have been prevented.” They say in their detailed document to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid that the deaths were associated with faulty candidate selection for the risky heart pump procedure, prolonged patient hospital stays, improper practices for obtaining patient consent and poor surgical management.

‘Appropriate action has been taken’

The complaint to Medicare and Medicaid regulators cited Loebe’s critical role as the chief of the heart transplant and the heart pump programs. But it also mentioned another key player: Dr. Anita Phancao, a cardiologist who heads the heart-failure team that collaborates closely with the transplant surgeons before and after heart transplant and pump implant procedures. It accused Phancao of “failing to provide standard of practice measures,” including managing patients without actually seeing them.

It also alleged that Phancao had secured consent for procedures from patients who were in a poor mental state, were hindered by a language barrier or possessed limited understanding of medical terms. In short, the complaints alleged, patients were not being educated properly before consenting to the pump implant procedure.

Jackson officials said Phancao’s status at the heart transplant and pump implant programs is unchanged.

Phancao, through Jackson’s public information office, declined to be interviewed for this story.

Phancao was the subject of two similar complaints through EthicsPoint — a portal for University of Miami employees to lodge anonymous complaints.

According to records examined by the Herald, one such complaint, lodged in December, elicited the following response two months later: “Various offices and JMH [Jackson Memorial Hospital] Risk [management] are investigating these concerns.”

A subsequent similar complaint through the same portal — it’s anonymous so it’s not clear if the submitter was the same person — brought forth assurance that “appropriate action has been taken.” Details were not provided.

Generally, heart transplant programs — like heart-pump implants — are judged on a variety of metrics, ranging from survival rates to length of time spent on waiting lists.

For the most part, survival rates of Jackson heart recipients are in line with national numbers, according to data published by the Scientific Registry of Heart Recipients. But variations have occurred. Data published in January 2022, a limited snapshot, show Jackson lagging in one-year survival rates — about 87% versus 93% nationally.

Jackson officials asserted that their transplant program accepts the sickest patients, including those who might be turned away by private hospitals. However, they acknowledged that the heart division has not been performing as well as the kidney, liver and other organ transplant programs and that they plan to make major personnel changes — a process that began last fall with the decision to search for a new leader to replace Loebe.

“We have to find out why there is a discrepancy between every other transplant program and heart,” Vianna, the Miami Transplant Institute director and the chief of Liver, Intestinal and Multivisceral Transplants, told the Herald.