‘The problem is poverty’: Florida removing more kids from poor families over alleged ‘neglect’

Tiffany Clark was eight months pregnant when a child protective investigator contacted her in January 2019 in response to a tip called in to Florida’s abuse hotline.

Clark told the investigator the truth.

Her first son, Kylhar, showed signs of severe autism. At 4, he still wore diapers, fed from a bottle and said little more than “mama.” He dashed out of unsecured doors, flailed on the floor in frustration and chewed on his hands with deteriorating teeth that were tough to keep clean.

On top of that, Clark was homeless, spending nights with family and friends, at cold-weather shelters or in hotel rooms or borrowed cars. A Medicaid driver transported her and Kylhar each morning to a clinic where Clark received her prescribed daily dose of methadone – the medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder that restored a sense of normalcy to her life.

Clark was overwhelmed, she told the investigator. She wanted to be a good mother and needed help.

She wouldn’t get it from the state of Florida.

When she applied for government aid, Clark, now 35, was told that emergency cash assistance came with a volunteer requirement. But she had nowhere to leave her son so she could do the work. No one from the state Department of Children and Families offered her housing, babysitting services or cash to pay for anything she needed to try to navigate the challenges of motherhood.

Instead, three weeks after her baby was born, the department accused the Palm Coast mother of neglect and took custody of both boys. Then they paid foster families each roughly $500 a month to care for her children.

Families like Clark’s are increasingly in the crosshairs of a child welfare agency that shifted its focus eight years ago from family preservation to protecting kids at all costs.

The move, sparked by news headlines about children who died when DCF left them in abusive homes, was supposed to rescue more kids from abuse. Instead, it triggered a flurry of removals for reasons that the department classifies as neglect but experts say are often just symptoms of poverty.

Neglect is a catch-all category that includes allegations of insufficient food, clothing, care or shelter, in addition to domestic violence. Along with inadequate housing, these allegations factored into 50% of removals in 2020 – up from 25% before the policy change in 2014, USA TODAY’s analysis of federal data found. The surge is the highest in the nation during that period.

About the series

This is an ongoing series about Florida’s child welfare system, which has taken an increasing number of kids into foster care without enough safe places to put them. Reporters at USA TODAY spent two years analyzing data and interviewing families, insiders and advocates, revealing how overwhelmed state officials put nearly 200 children into the arms of abusers, and how the system is stacked against battered women and downplays accusations against foster caregivers that when made against parents can result in them losing their children.

Contact the reporter

Suzanne Hirt, shirt@gannett.com

Most removal cases include multiple allegations against parents. In calculating the number of neglect and inadequate housing cases, USA TODAY excluded any cases that also cited allegations of abandonment, physical abuse or sexual abuse.

Even as Florida’s poverty rate has declined, removals citing neglect or inadequate housing have doubled. Meanwhile, fewer than 1 in 5 removals are because of physical or sexual abuse – a rate that has remained flat for more than a decade.

As part of its ongoing investigation into Florida’s foster care system, USA TODAY combed hundreds of DCF, dependency court and police records; examined state and federal expenditure reports; and interviewed nearly 100 birth parents, relatives, attorneys, child welfare experts, DCF child protective investigators, caseworkers and licensing specialists. The media organization also gained exclusive access to internal documents that provide a rare window into a child welfare system usually shrouded in secrecy.

The reporting revealed that DCF is increasingly separating children from the very families it is required by law to help.

Read the first investigation: Florida took thousands of kids from families, then failed to keep them safe.

To remove children for neglect, the state is supposed to show that parents either refused to supply basic needs even though they were financially able to do so or that they rejected state assistance. DCF must offer support or services that could alleviate safety concerns whenever possible; removal is meant to be a last resort.

But more than a dozen parents who lost their children for neglect told USA TODAY that the help they received from DCF, if any, was meager, impractical or exacerbated their problems.

Two mothers in different counties on Florida’s east coast were forced to leave the residences they shared with their parents so that their children could stay. Both mothers became homeless for months, even as courts and caseworkers pressed them for proof of jobs and income.

In another case, a Daytona Beach-area nurse had been applying for rental properties where she and her children could live on their own when her abusive partner overdosed. Rather than assisting the mother as she saved enough money for a lease and security deposit, DCF removed her three children.

And in Clark’s case, a DCF investigator provided a list of phone numbers she could call seeking housing. One of them was for an agency that agreed to help with living expenses only if Clark placed her unborn baby for adoption. Another was for a shelter several hours away from her family and her son’s speech therapist, records show. Clark did not have a vehicle or a cellphone.

“Neglect is supposed to be willful and malicious – those are very key words,” a former Escambia County case manager said. Like several of the child welfare workers USA TODAY interviewed, she spoke on condition that her name be withheld because she fears retaliation. “Instead of being cooperated with and presented other options, (poor parents) are just punished.”

DCF demonstrated that it can keep families together when its failure to do so attracts media attention. The department came under fire in November in a region known for having among the highest removal rates in the state. In a press conference, Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri blasted the nonprofit contracted by DCF to handle foster care there and in neighboring Pasco County for placing foster kids in “deplorable” and unsafe living situations.

Read the investigation: Florida blames mothers when men batter them – then takes away their children

In response, DCF reported that it reduced removals there by 50% in just six weeks, marshaling community resources and providing economic assistance in an effort it described as “transforming” child welfare. It was not clear from publicly available data how that statistic was calculated, and DCF did not provide an explanation in answer to USA TODAY’s request.

Regardless, the department is supposed to make those efforts statewide. Its stated goal is to try to prevent removal in 95% of cases, but it did so in just 33% of cases in some parts of the state last year, according to an internal quarterly review.

Frontline workers who can provide material support to the families they investigate say they are stretched so thin that they don’t have time to understand and address parents’ problems, and they fear repercussions if a child they leave at home is harmed.

The department’s budget lays bare its priorities: The nonprofits it contracts with to run child welfare at the local level paid out more than 10 times as much to foster and adoptive parents as they spent on services designed to prevent the removal of children from their homes – $429 million versus about $38 million, according to a 2021 DCF financial report.

The median monthly payment to foster households statewide is about $500 per child, with many caregivers taking in multiple children at a time. It’s money that experts said would be better spent helping birth families escape poverty and provide for their children.

Once children are removed, families face an uphill battle to get them back. Caseworkers load up parents with time-consuming tasks they must complete in order to prove they can keep their kids safe. Their schedules are stuffed with parenting courses, mental health and substance use evaluations, drug tests, therapy sessions and treatment programs. Such requirements would be a challenge for any parent; for those who lack housing or transportation, they can be crushing.

DCF would not grant USA TODAY an interview with Shevaun Harris, who took over as its secretary in February 2021. For months the department ignored or refused to fulfill multiple public records requests until an attorney demanded a response. In a written reply to USA TODAY’s questions, the department said its priority is to avoid removals whenever possible and that it strives to help families work toward reunification.

The department said Harris is mobilizing teams focused on economic self-sufficiency, substance abuse and mental health to address families’ needs holistically.

“Removing a child is a significant and complex decision that considers all family dynamics. Many times, these dynamics are rooted in economic instability, untreated mental illness or substance use, which show up in the form of neglect,” DCF wrote.

Last year, DCF submitted a five-year plan detailing how it would comply with the Family First Prevention Services Act, passed by Congress in 2018 to divert more funds to families with children at risk of entering foster care. The plan describes a goal of engaging families before they are in crisis and improving access to economic support and behavioral health programs.

Indeed, while some parents come to DCF’s attention for income-related issues alone, far more often those needs are combined with other concerns, USA TODAY’s analysis of federal data shows.

The department can – and typically does – craft cases for removal around more than one allegation. The most frequently cited alongside neglect and inadequate housing were drug abuse, alcohol abuse, physical or mental health issues or incarceration.

In 2013, the year before DCF shifted focus away from family preservation, Florida removed 14,310 children from their homes. About one-fourth of those cases – 3,689 – cited allegations of neglect or inadequate housing.

In 2020, removals fell to 13,392, a drop consistent with national trends as the coronavirus pandemic kept children out of school and hotline calls decreased. But the number of removals citing neglect or inadequate housing continued to climb, hitting 6,804 that year.

Meanwhile, removals for reasons that included allegations of physical or sexual abuse declined from 2,624 children in 2013 to 2,142 in 2020.

Again, when calculating removals for neglect or inadequate housing, USA TODAY excluded cases involving an allegation of abuse or abandonment – even when those claims may have been made against only one parent. The analysis is therefore “conservative,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

“If anything,” Wexler said, “it will understate the problem.”

Most of these cases involved white children. While the overrepresentation of ethnic and racial minorities in the child welfare system has been well documented nationally, the data shows that removals of Black children for reasons of neglect or inadequate housing in Florida have declined since 2008. For Latino children, however, the rate has increased.

Child welfare experts noted that data does not capture the complexities of every case: Some poor parents may battle substance abuse or mental illness to such a degree that their children require state intervention, though DCF can leverage behavioral health services to prevent removal.

Wexler said frontline workers can mistake poverty for neglect for a couple of reasons. A filthy home, for instance, is easy to see; the love an overwhelmed parent has for a child may be less visible. And complicating factors like drug use or depression often disguise a family’s underlying issue. To reveal the root problem, Wexler applies a simple test.

People with financial means can pay for private therapy, treatment or child care, Wexler said. “If the solution is money, the problem is poverty.”

A ‘stereotypical’ response by DCF

Money was never plentiful during Tiffany Clark’s childhood on Long Island in New York. Her mother worked hard to make ends meet, relying on food pantry donations and the kindness of friends to fill the gaps.

Her stay-at-home father spent his days drinking and smoking crack cocaine, Clark told USA TODAY and a psychologist who evaluated her for DCF, as evidenced in her case file. Alcohol made him mean, she said. He lashed out with words and sometimes fists until Clark fled to Florida to escape him with her mother and twin sister the summer she turned 15.

They moved into the Palm Coast apartment Clark’s grandmother shared with an aunt and cousin. DCF visited the following year to investigate an allegation against Clark’s aunt, who had struggled with substance misuse – an issue prevalent in the family, according to case records.

Clark’s half-sister on her father’s side died of a drug overdose. Clark’s father passed away because of complications from alcohol abuse.

Clark was prescribed opioids as a teenager after undergoing dental surgery and sought more from friends after the doctor’s order expired. When she progressed from pills to intravenous injection at age 24, she felt she had reached rock bottom and contacted a methadone clinic.

“I’m not doing what I was before methadone – pills like crazy,” Clark said. “(Methadone) changed my life.”

It also attracted DCF’s attention.

The department investigated her over concerns for her methadone use in early 2015 after Kylhar was born and again in late 2016 when she had a second son, whom she ultimately decided to allow a relative to adopt. Kylhar already showed signs of autism, and caring for him was a full-time job.

Clark planned to reduce her methadone dosage in 2018 before learning she was pregnant again. As with her first two pregnancies, a clinician upped her intake instead to support her body’s increased metabolism and stave off harmful withdrawal symptoms.

When DCF opened the new investigation in January 2019, it noted concerns about Clark's unstable housing and substance misuse, though Clark tested positive only for methadone, records show.

That case was still open when she dozed off in a Daytona Beach hospital while holding her 2-week-old son in early March, sparking the suspicion of a nurse in the neonatal intensive care unit where the baby was stabilizing from methadone exposure. The nurse dialed DCF.

Clark was “sleeping to the point of snoring” and had to be roused several times, the nurse reported, according to case records. Clark told USA TODAY that no one bothered to ask why she was so weary. She could’ve explained that she didn’t know night-to-night where she and Kylhar would sleep. That the exhaustion from giving birth without painkillers had not yet ebbed. And that the higher methadone dosage hit harder once her metabolism slowed postpartum.

Four days later, on March 6, 2019, a DCF investigator removed Kylhar to a foster home and placed the baby, Matthew, under protective custody in the hospital. Clark said she was hysterical and crying as child welfare workers led Kylhar away without his bottle or blanket.

“We’re as attached as you could be,” Clark said. When he was gone, “it almost felt like he died – like I was grieving the loss of him. … Why are they wasting their time with me when they could be taking a child who is not loved and is being abused?”

DCF built its case on more than a dozen “grounds for removal,” records show. The claim that Clark was so affected by her methadone that she could not stay awake to care for her kids was chief among them.

DCF’s response was stereotypical and steeped in stigmatization, said Dr. Mishka Terplan, a board certified physician in both obstetrics and gynecology and addiction medicine. Terplan is a medical director and senior research assistant at Friends Research Institute, a nonprofit with a mission to promote health and well-being.

“Removing kids for the reason that Mom is taking life-saving medication for a chronic condition is in conflict with the principles and practices of medicine and public health,” Terplan said. If health care workers or DCF believed methadone contributed to Clark’s drowsiness, they could’ve talked it over with her, contacted her treatment provider and connected her with postpartum support programs while “treating her with dignity and respect.”

Most of DCF’s grounds for removal were unsubstantiated, presented without crucial context or based on hearsay, according to USA TODAY’s review of the case files. Others that were verified or composed from Clark’s own admissions point to poverty rather than child safety issues, experts said.

For example, the department characterized Clark as ill-prepared to care for a newborn because she had not obtained WIC or food stamps and couldn’t access the crib and stroller she had in storage because she’d been unable to keep up with the rent. WIC stands for "Women, Infants, and Children" and is a federally funded nutrition program for certain low-income families. State officials never offered Clark help paying the bill or obtaining new items for the baby.

DCF alleged that Clark and Kylhar had been kicked out of a hotel and “law enforcement was called because … the child was running up and down hallways unsupervised,” court records state.

Clark told USA TODAY that Kylhar had climbed on a bag full of clothes to unlatch their hotel room door while she was in the bathroom, and that she had scrambled after him right away. She explained to the responding deputy that Kylhar, like many children with autism, often bolted from caregivers. The incident was so minor that the deputy told her to be careful and went on his way, she said.

Local law enforcement could find no record of the encounter in response to USA TODAY’s requests. A DCF investigative report shows that the version of events submitted in court came from an interview with an acquaintance of Clark’s who was not an eyewitness. The woman’s concerns were crafted from “statements of others” and “hearsay,” according to the report.

Kylhar also had decayed teeth, another common autism-related issue. He required a dentist that had the ability to sedate children for dental procedures. Clark said she’d obtained a referral but Kylhar was placed in foster care before she used it.

Again, no one asked Clark for an explanation, said Summer Boyd, a Jacksonville dependency attorney hired by Clark’s extended family to take over the case.

“If somebody had listened to her or me about what had gone on with Ky instead of just writing her off as a drug addict and not listening to what she had to say about being his parent, and if they had focused more on helping her get somewhere to live … I think they could’ve avoided removal altogether,” Boyd said. “I can’t think of anything they did for her in this case besides harm.”

‘Forced to make harsh decisions’

Several DCF investigators told USA TODAY that the failures in Clark’s case are common because of overwhelming workloads, insufficient time to assess families’ needs and fear of overlooking signs that children are in danger.

They described hurrying from home to home, leaving interviews with parents unfinished and paperwork incomplete in their rush to respond to reports rolling in to DCF’s child abuse hotline. The department fosters an optics-obsessed, “cover your ass” culture that prioritizes closing cases over assisting families, they said.

These problems are not new.

A 2018 peer review of Hillsborough County’s child welfare system commissioned by then-DCF Secretary Mike Carroll unearthed the same issues. The team was tasked with developing recommendations to improve effectiveness and keep children safely at home when possible.

The review found that the county’s poorest ZIP codes experienced the highest removal rates. Reviewers also noted that child welfare professionals fell short of prevention efforts required by law and were “unnecessarily risk averse due to the fear of child fatalities and media consequences.”

Last year, frontline workers echoed similar concerns in eight letters of complaint to DCF leadership that were obtained by USA TODAY. The letters describe investigators’ poor decision-making and dissatisfaction with the quality of their work due to caseloads that at times were nearly double the expected 15-case limit.

One person wrote that high caseloads caused investigators to make quick choices and hindered their “ability to do in-depth research on families.” Another recalled being “forced to make harsh decisions on families that are unwarranted.”

At least three of the 13 current and former investigators USA TODAY interviewed said children were not in danger in more than half of their cases. One supervisor among them estimated 80% of his unit’s cases were based on unsubstantiated claims and sucked up time that should have been spent saving children from serious abuse.

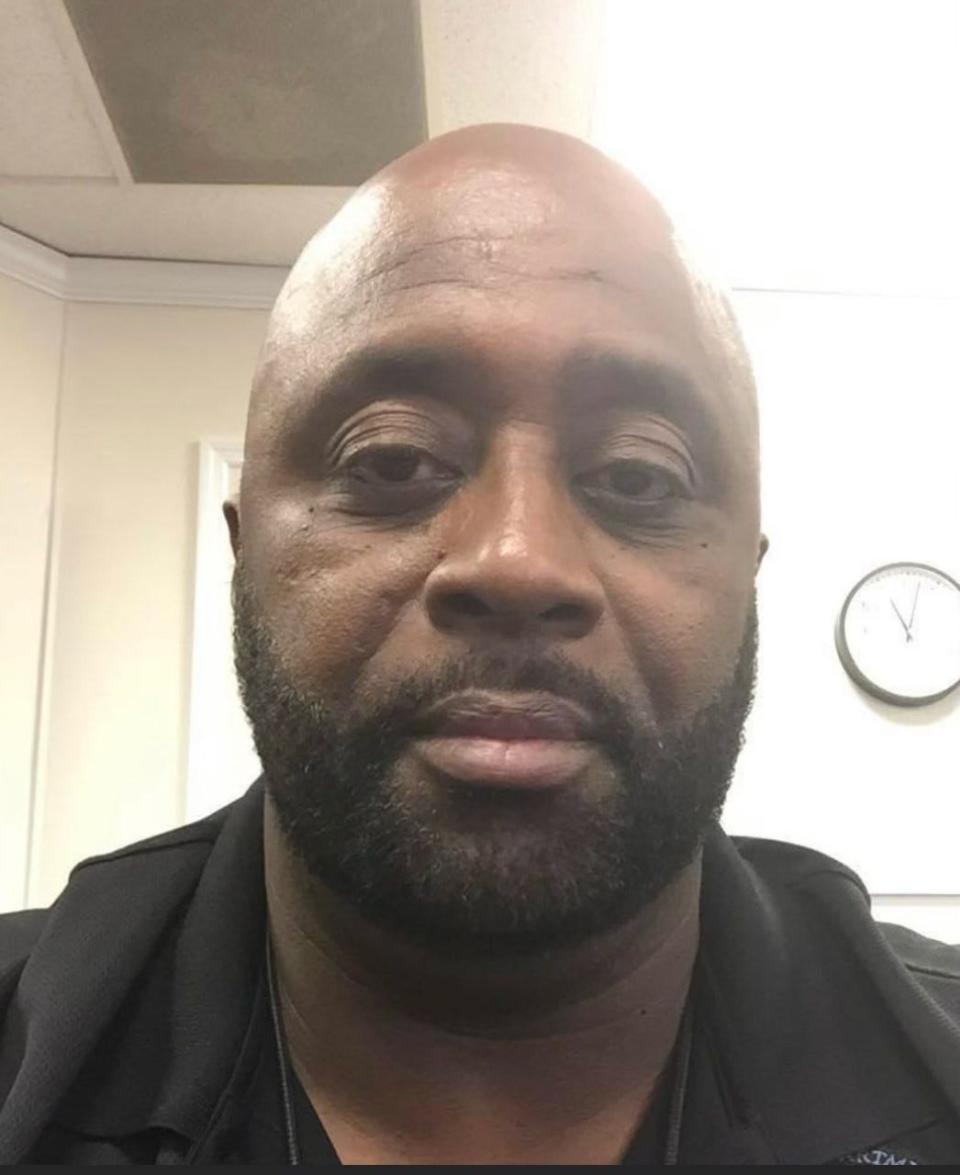

Dexter Walker, a former senior investigator who left DCF in June after 16 years, said he was troubled by how often reports about needy families were classified as parental neglect, prompting an adversarial approach rather than an offer of help.

“In my heart I felt we could’ve done services with these families, but we removed (their children),” Walker said. “(DCF has) enough money to take and keep these kids in foster care, but never enough to invest in prevention.”

The tools available to help investigators avoid removal depend on the 19 nonprofit agencies that contract with the department to oversee child welfare at the local level, according to a 2021 DCF review of revenues and expenditures. Each agency’s commitment to prevention is evidenced by how much it spends on support services for families, the review noted.

During the 2020-21 fiscal year, those nonprofits collectively put an average of just 5.3% – about $38 million – of their core funds toward prevention. Meanwhile, they paid out $595 million for foster parent stipends, caregiver training, case management and adoption promotion, plus more than $250 million in adoption subsidies.

Had Tiffany Clark been offered the money that foster parents receive, she could’ve secured an apartment, resolving one of DCF’s main allegations against her, she said.

“If we could give that stipend to parents, we could solve a lot of problems,” said Neil Skene, DCF’s special counsel from 2008 to 2010 and chief of staff at the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services from 2015 to 2017. “Let’s put more money in those homes and more care into those families to make them self-sustaining.”

Investigators told USA TODAY they were authorized to help poor families by paying utility bills, supplying gift cards and purchasing clothing and beds but simply didn’t have time.

Stephanie Harris, a former investigator in Daytona Beach, recalled logging countless 12-hour shifts followed by evenings of searching housing programs and mental health or substance abuse treatment options for parents. As her caseload increased, she could no longer pursue those efforts.

“When you have 20, 30, 40 cases, you don’t have time to breathe let alone make additional phone calls or stop at a resource center,” Harris said, adding that her superiors pressured her to “just remove” rather than slowing down to assist parents.

Those willing to put families’ best interests aside and focus on closing cases quickly are promoted, though speed is not synonymous with child safety, said Reginald Brady, a senior investigator with 26 years’ experience.

“The only way to survive in the department is … to word (reports) to make it look like you did what you’re supposed to do, work the bare minimum, throw things under the rug and bend the rules,” said Abigail, a former investigator who asked to be identified only by her first name for fear of retaliation. “That leaves kids unsafe and parents unsupported.”

Parents set up to fail, attorney says

Most parents battling to regain custody of their children are offered a case plan – a checklist of classes and evaluations to complete as proof they’ve addressed the issues that brought DCF to their door.

The stakes are high: If the state isn’t pleased with parents’ progress within a year, it may move to terminate their rights so that children are available for adoption.

Clark's family recognized that she could lose her kids forever and felt her court-appointed attorney favored DCF. Clark’s grandmother hired Boyd, the Jacksonville attorney, to take over the case soon after Clark’s sons were removed from her care.

DCF planned to expedite termination of Clark’s parental rights, Boyd said. She pressed the department to give Clark a case plan and in early June – three months after Clark’s kids were taken – DCF agreed.

Even then, the hurdles were daunting: Parents often must squeeze multiple appointments a week into their schedules in addition to securing stable housing or income.

“DCF comes in like a tidal wave and you have to repair and put your life back together again with a teaspoon,” Boyd said. “They’re setting (parents) up to fail.”

Clark submitted to weekly drug tests, took parenting classes, attended individual and group therapy sessions and underwent assessments for substance abuse and mental fitness. She paid out of pocket for her methadone prescription because she lost Medicaid coverage when DCF removed her kids.

Clark’s grandmother moved back to Florida from New York to help Clark find and pay for an apartment in Daytona Beach, and Clark reduced her methadone intake – as she had planned.

The same relatives who had taken in Clark’s second son agreed to adopt her newborn, Matthew, but the baby spent 10 weeks in foster care before a court granted the family custody in June 2019.

Kylhar finally returned to Clark in August 2020 – but not because of anything DCF had done to improve Clark’s circumstances. Kylhar’s foster parent could no longer keep him, and caseworkers “couldn't figure out where to put him,” Boyd said, so they urged her to file a motion to reunify the mother and son.

Clark believes child welfare workers dismissed her as a drug addict and underestimated her resolve.

“They probably thought I didn’t care and thought I was stupid,” Clark said. “I love him to death so they picked the wrong person.”

The hardships Clark faced are commonplace, according to court records and interviews with parents and more than 30 current and former caseworkers and dependency attorneys.

A Miramar Beach father who relapsed into alcohol abuse due to financial stress and grief over his dad’s death completed a treatment program, attended weekly group meetings and engaged in therapy while maintaining stable housing and employment. His case continued for a year because caseworkers had not once administered the drug tests required to prove his sobriety and admitted to attempting only two unannounced visits to complete home safety checks in a span of six to eight months, court records state.

Caseworkers refused to reunite a Freeport mother with her infant son even after she completed substance abuse treatment, went to therapy, found a job and cut ties with the friends who had influenced her drug use. They pushed her to move out of her family-owned residence where she lived rent-free, viewing it as a sign of instability, according to the mother and her attorney. The 28-year-old could not afford a new home and ultimately signed over permanent guardianship to her mother.

“The parent is always subject to the opinions of other people – not facts, but opinions,” said Laguerra Champagne, a Pasco County dependency attorney. “The system is not forgiving, it's not sensitive and it deals with a whole different set of rules than it expects parents to adhere to.”

Even when parents do all that’s asked of them, those caseworkers and dependency attorneys told USA TODAY, cases drag on for months due to administrative delays.

High turnover, heavy workloads and unfilled positions plague child welfare offices across the state, a DCF internal review released in July confirmed. In one especially strained Tampa-area division, attorneys for the department carried 165 cases per person. Case management agencies – which monitor parents’ achievements and keep tabs on foster children – were similarly overburdened.

Candice Brower, who oversees court-appointed attorneys for parents in 32 north Florida counties, said cases in her region sometimes stagnate for so long that her office is forced to ask that judges hold DCF in contempt. “It’s a last resort,” she said.

The constant caseworker churn prevents courts from getting feedback about families in a timely fashion and stalls parents' efforts to reunify with their children.

“Anything that requires a caseworker, it’s all delayed. We’re waiting weeks for referrals (to case plan services) and then the caseworker quits,” said Hilda Griffis, a Clay County dependency attorney. “(The state has) hamstrung parents in every possible way.”

A troubling aftermath

Clark’s family endured the effects of her DCF case long after her boys returned from foster care.

Though Clark’s relatives had asked to take in baby Matthew just days after DCF removed him from Clark’s care, caseworkers instead placed him with Jennifer Glover-Zappas, a new foster mother who had been involuntarily hospitalized for attempted suicide just two months prior, police records show. It was her second such hospitalization. The licensing agency failed to uncover the reports in a background check, Flagler County deputies told USA TODAY.

When relatives received custody of Matthew, they reported suspicious markings on the baby’s buttocks. A medical evaluation found multiple bruises in various stages of healing. Deputies did not have sufficient evidence to determine who was responsible but worked with local DCF officials to ensure Glover-Zappas’ foster license was revoked, Sgt. Michael Miller said.

More: Foster kids starved, beaten and molested, reports show. Few caregivers are punished.

Glover-Zappas – whom the state paid at least $1,242 to care for Matthew, records show – told USA TODAY that any reports of child abuse in her home were “unfounded” and that her family was “told we would adopt (Matthew).”

The 18 months that Clark’s oldest son spent in foster care also were troubling for the family.

Caregivers and caseworkers met with the same difficulties that Clark had managed for years. Foster parents reported that Kylhar bit his hand, banged his head and ran away from day care staff. Caseworkers struggled to find a dentist who offered specialized care for children with autism.

Kylhar was shuffled between four foster homes – including a six-month stint on Florida’s west coast. Clark's mother had to borrow a car for the 10-hour round-trip drive to visit him. They were allotted only an hour together.

Kylhar’s foster parent there did not enroll him in school, according to case records. His guardian ad litem representative, now a circuit judge, wrote in a motion filed with the court that after five months in state custody he still had not received dental care.

“All responsible agencies have miserably failed ... and have allowed him to needlessly suffer,” the August 2019 motion states. “Ironically, the Department has failed to provide the very care which served as one basis of removal.”

When Kylhar came home more than a year later, the progress he had made in speech and physical therapy prior to entering foster care was gone, Clark said. He had frequent “meltdowns,” banging his head violently on floors and walls. Clark believes they resulted from the trauma of their separation.

Now, after being home for nearly two years, his tantrums are fewer. Kylhar is enrolled in a program for special needs children at his elementary school. He sings the alphabet and chants words like “off” and “bye” when he wants to remove his shoes or head home. He’s less apt to run off, and he chews on a soft toy that hangs on a cord around his neck instead of biting his hand.

Even at age 7, he can be clingy, Clark said, but she’s grateful for it. She knows some children with autism shrink from physical affection. She scoops him up, and they clutch each other close. Kylhar leans back to give her a kiss.

“I remember exactly what it felt like when they took him, and I didn’t have a chance to do that,” Clark said. “They say you don’t know what you have until you lose it. But I did know.”

Contributing: Aleszu Bajak

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Florida removing poor children from homes over alleged 'neglect'