Progress is like a pendulum that sometimes swings backwards | Opinion

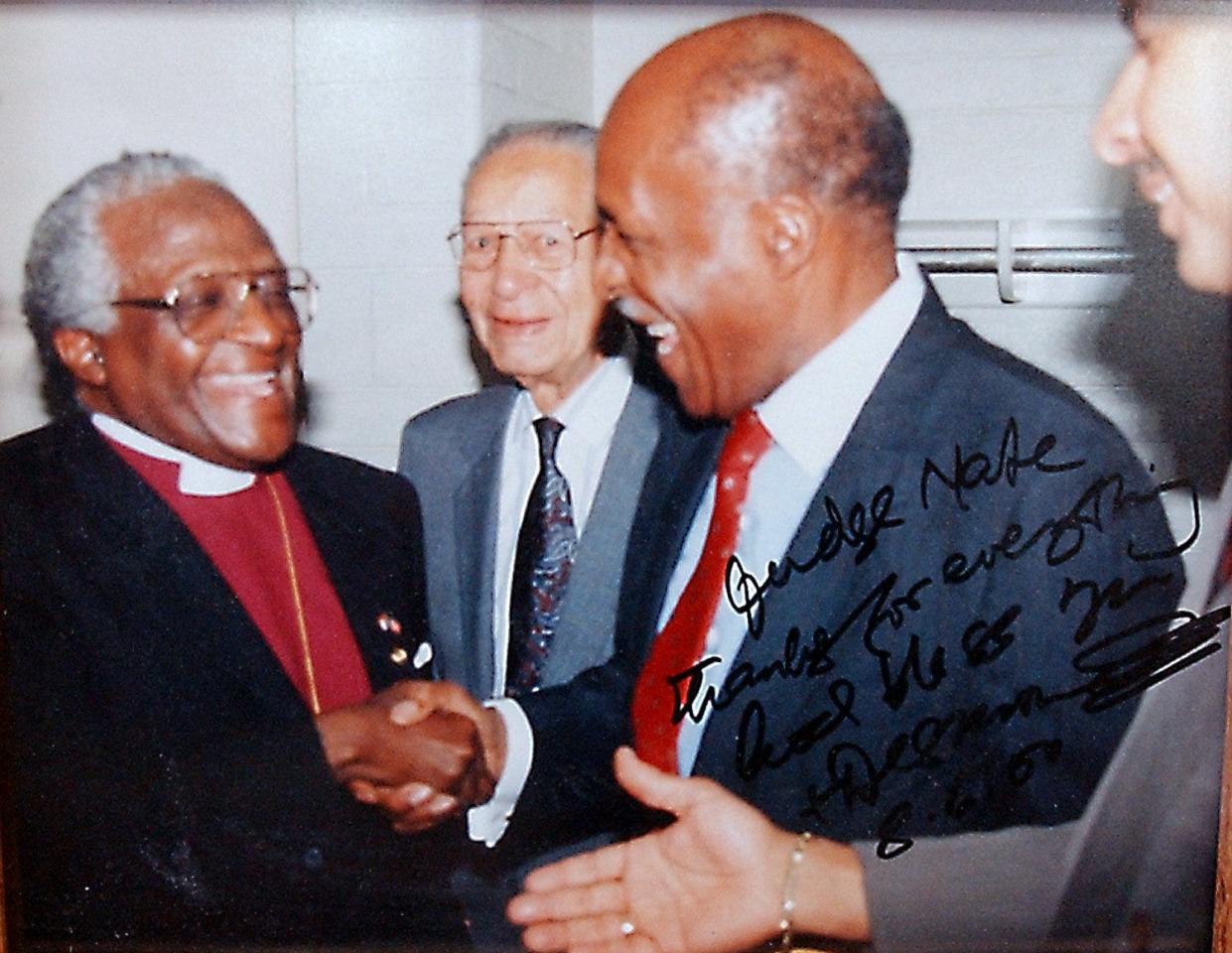

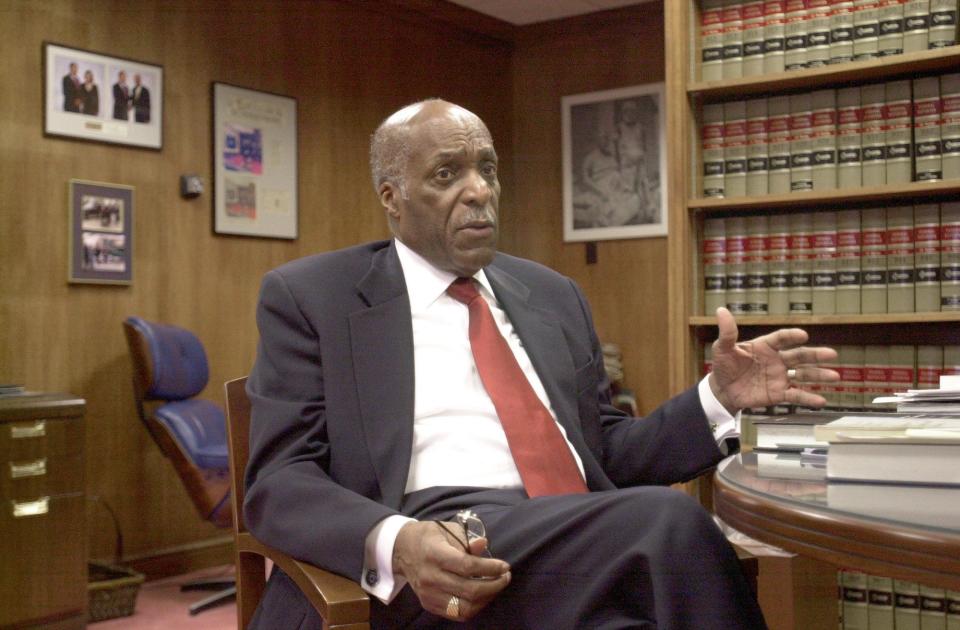

My father, Judge Nathaniel R. Jones, spent his life fighting for justice and change. He first answered the call as a young boy when he saw racial injustice and wanted to do something about it. His mother, knowing her fifth grade education would allow her to take him only so far (she went back and got her high school diploma in her 60s and valedictorian of her class …), made sure to expose him to people who could take him on the next stages of his quest.

Thanks to his mother’s foresightedness, young Nathaniel met and became the protégé of a local Black attorney who taught, guided and inspired him. J. Maynard Dickerson instilled in him a deep sense of hope − but not a blind faith. A hope that could be fulfilled with hard work and dedication and a constant focus on the goal. In turn, my father passed that hope on to me and the countless other people he mentored and influenced.

Progress can be made if we believe and work for it

Daddy never stopped reminding me that progress can be made, if we believe and work for it. And he never let me give up or give in to despair. And he both taught and showed me the power of politics to effect change and always encouraged me to be a part of it.

Emulating his mother’s efforts to expose him to politics and the social justice movement at an early age, he did the same for me, folding me into his own activities long before I can even remember. My very first outing in life, the day after my parents brought me home from the hospital, set me on the path: "On yesterday, we went to an NAACP meeting at church, where Nate presided," my mother wrote in a letter to her parents. "Steffie was real good."

That was the first of a long line of experiences Daddy included me in. Carrying me in my little baby basket to the Los Angeles Coliseum to hear JFK give his acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic Convention. Rousing my sister and me out of bed just after midnight so that we could greet Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who landed in the wee hours for an event the next morning during his 1968 presidential campaign. Taking me with him to the annual Gridiron Dinner and allowing me to sit on a bench outside the hotel ballroom so I could watch the movers and shakers come and go.

By 1972, I was ready to get directly involved. So, three nights a week after school, my parents dropped me off at the local McGovern campaign headquarters to volunteer. I felt very grown up and cool and thought that if I worked hard enough, McGovern would win.

So, I was devastated when he lost. After staying up crying half the night, I wandered into the bathroom where Daddy was shaving, sat on the edge of the tub, and told him I would not go to school that day. "Everybody will laugh at me."

"Who cares what they think? They don’t know anything," he said. "They’re just repeating what they heard their parents say. Losing doesn’t mean you were wrong. You did the right thing and worked for what you believed in. So you go to school and hold your head up. And if anybody laughs at you, laugh right back and tell them they picked the wrong man."

He also told me that Nixon wouldn’t finish his term because he would probably be impeached as a result of the "sabotage" that was just coming to light, but that’s another story.

More: The day the Good Judge went ridin’ with Biden | Opinion

Thirty two years later, the morning after George W. Bush defeated John Kerry and my then-boss, John Edwards, I once again found myself sitting on the edge of the bathtub watching Daddy shave as I moaned about how awful the election results were.

Progress is like a pendulum that sometimes swings backwards

He listened for awhile and then without missing a whisker, said "You think THIS is bad? Imagine how we felt in 1956 when Adlai Stevenson lost again − for the second time. And we didn’t have a Civil Rights Act or a Voting Rights Act or members of Congress or governors or mayors. We didn’t just elect a Black man to the Senate. We didn’t have any of the resources or powers or tools that you have now. But we didn’t give up. We kept fighting. We focused on 1958 and got a Civil Rights Bill passed. And then in 1960, we elected Jack Kennedy president."

"Progress isn’t like a freight train just barreling forward. It’s a pendulum that sometimes swings backwards," he continued. "The important thing is not to let go, but to always keep pushing forward so that the next time, you move even further ahead. So feel sorry for yourself all you want today. But tomorrow, get to back to work."

Four years later, almost to the day, as I sat next to him watching Barack Obama declared the winner of the 2008 presidential election, I turned to him to see tears streaming down his face. I asked him if he was emotional because he thought he would never see this day.

"No," he said softly. "I always knew I would."

I reminded him of what he told me four years before about not giving up the fight. He chuckled and said, "Maybe one day you’ll figure out your old man knows a little something, kid."

The eight years of Obama were hopeful ones for him and all of us. But he also saw the efforts to roll back those gains, and he consistently warned us all to be vigilant. Not to sit on our laurels or to believe the fight was over. And sure enough, as he dreaded, despite his efforts, 2016 saw the election of Donald Trump.

That election broke my father’s heart. It wasn’t just the fact that the country had elected someone so unfit, but that so many of his friends and colleagues supported a man and a movement that were hellbent on destroying everything he believed in, had worked for, fought for his whole life.

In the weeks after the election, he wrote to an old friend: "It seems that all I believed in and hoped for is about to wind up in rubble. The inherent goodness that I believed to be buried inside of most people, is nonexistent. The rationales given by the so-called angry masses for electing a character such as Trump do not pass the test of reasonableness. I am angry, depressed and just plain disheartened as I realize that mortality tables say that I will not be around to contribute to any rebuilding or restoration that takes place, if it ever does."

"If it ever does …" These words are one of the few instances I know of that Daddy admitted that his faith was so badly shaken − the pendulum had swung back so far − that he feared we might not recover from a dire situation.

But over the next three years, he continued to work and continued to fight and, as his body weakened and his strength waned, he frequently expressed frustration that he wasn’t physically strong enough to engage as much as he wanted, but he kept trying. Even during his last illness, he repeatedly insisted he needed to "get out of here and get back to work."

He never stopped believing there was something to fight for. And he never stopped believing that fight was worth it and could be won.

Just a little over a month before he died, I sat beside him in the hospital, my feet propped up on his bed as we ate ice cream and watched the House of Representatives impeachment vote. When Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced the vote and slammed down her gavel, Daddy pumped his fist, gave a thumbs up, firmly nodded his head and said, "Good!"

He knew the Senate would not vote to convict − "The Republican Senators don’t have the guts," he said − but he believed the impeachment was a step in the right direction. And he felt hope again that this country he loved would right its footing and begin once again, to bend the arc back toward justice.

As he predicted, Daddy didn’t live to see that happen. And throughout 2020, I worried that it never would. COVID-19, George Floyd’s murder, the summer protests, an increasingly erratic and dangerous president instilled grave doubts. But throughout that year, I continued to work with hope and belief, because that’s what my father taught me to do.

On election night 2020, the first ever without my father, when early returns made me fear that the country had lost its collective mind and would keep an unfit despot in power, I felt frightened and alone. But then I heard Daddy’s calming, steady voice in my heart, clear as a song: "Stephanie, Stephanie! Calm down. They haven’t even counted the votes yet. Be patient!"

And, as usual, he was right. Because when the counting was done, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris won a clear victory. A step back from the brink and toward the right path.

In the three years since that election, we’ve had setbacks, but we’ve also made progress. The Supreme Court’s extremist conservative majority has ground its heel into civil rights, workers’ rights, affirmative action and women’s reproductive rights. But we have also seen grassroots movements push back with great success and have elected good people to the House, Senate, governorships, state legislatures and city government. We have celebrated the appointment and confirmation of a record number of highly qualified federal judges committed to civil rights and justice, including the first Black female Supreme Court justice.

We are now heading into another consequential presidential election, as important as any in my − or my Daddy’s or the nation’s − lifetime. The outcome will determine whether we will continue on the road my father helped to pave or lurch backward on a path this country may not survive.

Progress is slow but inevitable

As I look forward toward the fight ahead − four years since my precious father’s great and good heart gave out − I am encouraged and strengthened by the example he set for me since I was a baby. I urge everyone else who cares about justice, peace and the country and world we all live in to also remember the lessons The Good Judge taught us:

Change is possible, and progress, while slow, is not only possible, but inevitable … If we work for it, fight for it and never, ever give up. And if you feel it’s too much to bear, take a moment or a day to feel sorry for ourselves. But tomorrow, get back to work.

Daddy was right far more often than he was wrong. But he was uncharacteristically incorrect about one thing: his prediction that "I will not be around to contribute to any rebuilding or restoration that takes place" was way off. He may not be here in person, but whenever any of us who loved him and learned from him grasps the arc of the moral universe and bends it even a little closer toward justice, his hand is on ours and he is contributing to the rebuilding and restoration he dreamed of.

Thank you, Daddy. We’ve got this because you showed us how. Funny thing, it turns out my old man did know a little something, after all.

Stephanie J. Jones is president of The Call to Justice Foundation, an organization founded by her late father Judge Nathaniel Jones to empower a new generation of civil rights lawyers, advocates and activists to answer "the Call" to civil rights and social justice.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Nathaniel Jones: Progress may be slow, but is possible and inevitable