A Progressive Civil War Threatens The Left’s Power In Rhode Island

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In just a few years, Rhode Island has gone from a Democrat-dominated state where conservative party leaders shut progressives out of policymaking to a hotbed of left-leaning legislative activity.

The timing was right. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) won the Democratic presidential primary in Rhode Island in 2016, and the state’s progressive community took advantage of the momentum.

But now the controversial tactics of the Rhode Island Political Cooperative, or Co-Op, an influential upstart, are driving a wedge between progressives.

The Co-Op, a group that provides campaign services and infrastructure to candidates it endorses, has declared war on any Rhode Island state lawmaker who does not share its strategy of opposing anyone affiliated with the pre-2020 Democratic leadership team in Providence. The Co-Op expelled one of the lawmakers elected on its slate in 2020 and is mounting challenges against two other prominent progressive lawmakers.

“I don’t understand what their approach is and what they hope to accomplish,” said Patrick Crowley, secretary-treasurer of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO. “They seem as intent on unseating pro-labor and progressive legislators as they are on attacking or unseating a conservative.”

We are building, for the first time in this state, a real movement.Matt Brown, co-founder, Rhode Island Political Cooperative

The battle lines are basically: organized labor, the Rhode Island Working Families Party and many mainstream environmental groups arrayed on one side. The Co-Op, the Sunrise Movement’s Providence chapter with which the Co-Op is closely aligned, Black Lives Matter Rhode Island, and many members of the Providence chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America are on the other. Prominent members of the rival factions are barely on speaking terms.

Some veterans of state politics believe the conflict, which has grown nasty and personal, is jeopardizing the gains that the left has made in recent years.

“Instead of the variety of left organizations in the state ― that more or less support the same policy program ― getting together and attempting to maximize their power, we’re turning to personality-driven infighting and sectarianism,” said a left-wing Rhode Island activist who requested anonymity to protect professional relationships.

The fight over the future of progressive politics in a solidly Democratic, albeit small, state mirrors debates raging on the left across the country. Nearly seven years after Sanders’ first presidential run expanded the left’s vision of what is possible, activists and organizations with similar policy goals are at odds over when electoral idealism crosses the line into self-destructive naivete, when purity tests are necessary versus when they unnecessarily alienate allies, and the degree to which personal ambition lurks behind movement demands.

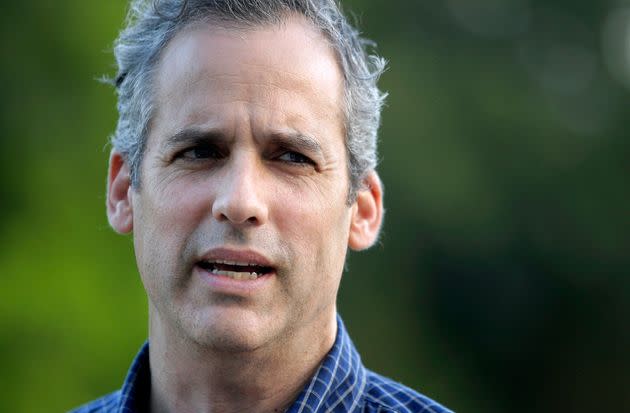

Matt Brown, a Co-Op co-founder and former Rhode Island secretary of state running for governor, and state Sen. Cynthia Mendes, a registered Republican until 2016 who underwent an ideological transformation and is running for lieutenant governor alongside Brown, maintain that they are simply more optimistic about restructuring state politics to address urgent challenges like climate change.

In 2022, the Co-Op plans to run 50 candidates for state and local offices with the goal of obtaining a true, progressive governing majority. Eliciting criticism from people and institutions on the left who have employed less effective tactics in the past is an unfortunate byproduct of the Co-Op’s commitment to changing outcomes, they say.

Other progressives “have accepted and believe that progressives will be in a permanent governing minority and therefore the only thing we can do is support and work with the leadership so we can get some crumbs, some incremental something,” Brown told HuffPost in an October interview. “Our feeling is that we are building, for the first time in this state, a real movement.”

Infiltrating The Old Boys Club

Although Democrats have had a veto-proof supermajority in Rhode Island’s state legislature for more than a decade, they’ve historically had a conservative streak that is rare for Democrats in the Northeast.

Rhode Island was one of the only blue states to adopt a photo ID requirement for voters ahead of the 2012 elections. State lawmakers also cut taxes for wealthy residents in 2014. And top Democrats, such as state Senate President Dominick Ruggerio and then-House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello, regularly won the endorsement of abortion rights opponents and earned “A” ratings from the National Rifle Association.

By 2016, progressives succeeded in landing blows against the reigning leadership clique that put Democratic leaders in Rhode Island on notice. In the Democratic legislative primaries that June, Marcia Ranglin-Vassell, a Jamaican-born public school teacher and first-time candidate, unseated the state House majority leader, an opponent of abortion rights. Ranglin-Vassell’s win was one of four candidates that the state chapter of the Working Families Party successfully ran against more conservative Democratic incumbents in 2016.

“These victories send a clear message to the legislature — it is time for some big changes,” Georgia Hollister Isman, the WFP’s Rhode Island state director, told HuffPost at the time.

For the most part, the legislature didn’t listen. Mattiello, in particular, used his power to block consideration of a $15 minimum wage, a bill mandating a transition to renewable energy, and a higher income tax bracket for the state’s wealthiest families.

In 2019, Mattiello finally stopped holding up codification of abortion rights into state law, while still voting against the legislation. It was enough to anger some conservative allies, but too little to ingratiate him with progressives.

In November 2020, Republican candidate Barbara Ann Fenton-Fung ousted Mattiello by a whopping 18 percentage points. She did it with quiet help from progressive volunteers.

After voicing my concerns [about certain decisions], I didn’t feel they were being heard in a way that there was going to be meaningful change.State Sen. Kendra Anderson (D)

“It wasn’t about her,” said a Rhode Island progressive activist who knocked doors for Fenton-Fung. “It was about the larger power structures of what it would mean for him to not be speaker any more. And one more Republican in that chamber doesn’t mean a thing.”

On a separate but parallel track, the Co-Op launched in 2020, running 24 candidates for state and local offices on an ultra-progressive policy platform and a pledge not to support the existing Democratic leadership team in the state legislature.

Some of the Co-Op’s candidates, like Brandon Potter, a car salesman who was raised by an impoverished single mother, had the support of other groups like the WFP, Planned Parenthood and Reclaim Rhode Island, a Sanders-inspired group that does not support the Co-Op’s leadership litmus test.

But in other cases, the Co-Op’s lack of relationships in Democratic Party politics enabled it to take risks that other groups were unwilling to take. For example, the Co-Op was one of the only major groups to endorse Mendes and queer Black activist Tiara Mack, both of whom won their state Senate races.

The Co-Op asked the individual candidates it backed to contribute a few thousand dollars in dues to pay for a variety of campaign consulting services that the Co-Op provided. Mendes and Mack both credited the Co-Op for providing much-needed advice, expertise and access to fundraising resources.

“I had someone on the Co-Op staff that I could call every single day of the week during the busiest months of my campaign and just yell, cry, scream and say, ‘How are we going to get this back on track?’” Mack told HuffPost. “I felt like my money at the time was spent wisely and was a really good use of time.”

In total, eight of the Co-Op’s state legislative candidates prevailed in 2020, part of a larger progressive wave that elected upward of 15 new progressive lawmakers.

‘They Vilify Other Progressives’

After the 2020 elections, the overwhelming majority of Democrats in the state House voted to make K. Joseph Shekarchi, who served as majority leader under then-speaker Mattiello, the next speaker. Just one lawmaker voted against him; eight others were absent or abstained.

Shekarchi, who is openly gay and half Iranian-American, is more moderate than the Co-Op’s candidates. But he received the votes of many progressives who saw him as more receptive to working with them than his predecessor.

Potter, who unseated a conservative Democrat in the September 2020 primaries and went on to narrowly defeat a Republican in the general election, was one of them.

Given Mattiello’s loss, Potter did not see voting for a different member of the pre-election House leadership team as a violation of his campaign promise to vote against then-House Speaker Mattiello.

In a statement explaining his vote, Potter said that he received assurances from Shekarchi and the new House Majority Leader Chris Blazejewski, a Providence progressive, that the legislature would be more collaborative and receptive to progressive demands.

The Co-Op disagreed and immediately expelled him from its ranks, adding that it had warned Potter in advance of its plans to expel him if he voted for Shekarchi.

But Brown admits that he and the other two Co-Op co-chairs, state Sen. Jeanine Calkin and Jennifer Rourke, had made the decision to expel Potter on their own ― without consulting the other lawmakers elected on the Co-Op slate in 2020.

By this September, when the Co-Op announced 24 of its proposed 50 state and local candidates, state Rep. Brianna Henries, and Calkin, a sitting lawmaker on the Co-Op’s 2020 slate, were the only Co-Op candidates elected in 2020 who were still affiliated with the Co-Op.

We are committed to justice and democracy not just for our state government, but for our own internal organization as well.The Rhode Island Political Cooperative

The Co-Op chalked up the departures to the lawmakers’ graduation to the status of “alumni.”

But at least two 2020 Co-Op candidates told HuffPost that they had grown disillusioned with the group’s decision-making process, including how Potter was expelled.

“The [Co-Op’s] power structure was still replicating and mimicking the same exact power structures that we critique at the state level,” Mack said, comparing the trio of Brown, Calkin and Rourke to the trio of the governor, state House speaker and state Senate president.

State Sen. Kendra Anderson told HuffPost she left the Co-Op for a variety of reasons, including a requirement that she publicly support a state-level minimum wage of $19 an hour. Anderson, who represents a centrist-to-conservative constituency in Warwick, believed the position would be politically untenable.

And, like Mack, Anderson grew tired of the top-down style.

“After voicing my concerns [about certain decisions], I didn’t feel they were being heard in a way that there was going to be meaningful change,” she said.

The Co-Op’s most controversial decision was to run candidates against two sitting Democratic lawmakers with progressive reputations: state Sen. Dawn Euer and state Rep. Karen Alzate.

Euer was chief co-sponsor of the Act on Climate bill, which requires Rhode Island to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and became law in April.

Alzate, chair of the legislature’s Black and Latino Caucus, is chief co-sponsor of a bill to raise the state’s marginal income tax rates on annual earnings of $475,000 or more.

“The Rhode Island Political Co-Op is toxic to the progressive movement in Rhode Island,” Potter told HuffPost. “It bothers me how much they vilify other progressives.”

Criticism Of Candidate Vetting ― And Communication

Incidentally, the two candidates that the Co-Op recruited to challenge Euer and Alzate, respectively, flamed out rapidly.

In late September, the Co-Op withdrew its support for Jennifer Jackson, the candidate challenging Euer, after it emerged that Jackson had expressed a number of conservative views on Facebook. She had reposted memes lamenting employer vaccine mandates, policies that supposedly prioritize refugees over native-born unhoused people, and prohibitions on religion and corporal punishment in public schools.

Days after the Co-Op withdrew its backing, Jackson ended her bid.

In early October, Tarshire Battle, who was challenging Alzate, dropped out after a similar series of conservative Facebook posts surfaced. Battle had called for a religious exemption to vaccine mandates and shared an article accusing atheists of smearing the socially conservative retail chain Hobby Lobby.

In a statement announcing her withdrawal, Battle, who is Black, implied that scrutiny of her social media posts was motivated by racism. “I and other Black and brown working-class women in the Co-Op have faced relentless attacks against us,” she said.

Asked for his response to the notion that challenging Euer and Alzate is a waste of resources for a progressive group in Rhode Island, Brown stuck to his guns, expressing hope that the Co-Op would still find candidates to replace Jackson and Battle.

“Those are legislators that we think need to be challenged by people who are going to vote against the current leadership,” Brown said.

What they’re asking us is, ‘Get in line and play the tactical game the way that we’ve been playing it.'State Sen. Cynthia Mendes (D)

Brown acknowledged that he, Calkin and Rourke had made the “final” decisions about which candidates to recruit and which lawmakers to challenge, but denied knowing about Battle and Jackson’s comments on vaccines.

Mack disputes this version of events, recounting that she was rebuffed when she asked the Co-Op leadership team to look into claims that Jackson was an “anti-vaxxer.”

“It was known beforehand that she had those sentiments,” Mack said.

Mack also said that her private appeals not to challenge Euer and Alzate fell on deaf ears.

The Co-Op is “white folks ― white men, white women ― who want to just take power into their own hands and don’t want to dismantle the white supremacist systems that run our country,” Mack said. “That is not justice and liberation. That’s recreating the wheel and filling it with our friends.”

Rourke, a state Senate candidate and member of the Co-Op’s reigning trio, is Black.

In an apparent nod to complaints about the closed nature of the Co-Op’s decision making process, the Co-Op adopted a new set of rules in late October, about a week after HuffPost first reached out for this story. The expulsion of existing Co-Op members and approval of new members, as well as “a variety of other strategic decisions for the organization” will now be subject to a vote by all Co-Op-endorsed candidates, according to a statement released by the Co-Op.

“We are committed to justice and democracy not just for our state government, but for our own internal organization as well,” the group added.

Divergent Theories Of Change

The aftermath of Rhode Island’s 2020 Democratic legislative primaries, in which progressives made significant gains, is like a Rorschach test for warring factions of the state’s left.

Under Shekarchi and Ruggerio’s leadership, the legislature acted on a series of bills that had gone nowhere during previous sessions. Among other things, Rhode Island Democrats passed a landmark climate action bill, and adopted the $15 minimum wage.

To the Co-Op, the progress is evidence that their aggressive approach is working. Now, to make additional progress, more Co-Op primaries are needed, not fewer of them, argue members and allies.

“What they’re asking us is, ‘Get in line and play the tactical game the way that we’ve been playing it,’” Mendes told HuffPost. “What I like to say is: ‘Tell me when that was fucking working?’ Because it wasn’t.”

The Co-Op’s detractors see a more complicated picture. While the Co-Op’s successes may have had a positive impact over the course of one fruitful election cycle, they argue that there’s more than enough room for the group to overplay its hand.

Potter, who recalls personally assuaging constituents’ fears of the word “progressive” during his Democratic primary, worried that the Co-Op was tempting fate in what is likely to be a less favorable cycle for Democrats.

That pendulum can swing back and forth pretty quickly.State Rep. Brandon Potter (D)

“They’re definitely fragile gains,” Potter said of progressives’ 2020 pickups. “That pendulum can swing back and forth pretty quickly.”

One area where critics fear that the Co-Op has already set itself up to lose ground is Mendes’ seat, which includes parts of East Providence and Pawtucket. Mendes won thanks in part to displeasure with the incumbent William Conley’s support for a new housing development, and the veteran lawmaker’s anemic campaign.

Some progressives worry that the Brown and the Co-Op’s recruitment of Mendes to run for lieutenant governor is likely to result in her replacement with a less progressive state senator.

Mendes rejected this analysis, saying that party leadership would have run someone against her anyway. She is confident that schoolteacher Greg Greco, the Co-Op-endorsed candidate to replace her, will prevail.

“What people consider ‘leaving [a seat] vulnerable’ is this very old, political playbook,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be all about me.”

Perhaps more important, critics raise strategic objections to the Co-Op’s entire approach, fearing that it undermines their shared agenda. They argue that Speaker Shekarchi has proven far more amenable to progressive demands than his predecessor, Mattiello.

Making opposition to Shekarchi ― or any other members of the pre-2021 leadership team ― the prerequisite for avoiding a primary challenge, risks being seen as punishing Shekarchi for moving leftward and embarrassing the progressive lawmakers who have cultivated him, according to this theory. That in turn, the detractors say, could actually lessen the appetite for left-wing legislation in a state where the electorate has shifted to the left only recently.

“It sends a message to lawmakers that they shouldn’t try to engage on these issues because the perfect is the enemy of the good,” Euer, the chief sponsor of the Act on Climate bill, told HuffPost.

But the Co-Op wants a state legislature where the chances of enacting a suite of Green New Deal bills that goes beyond Act on Climate, or raising taxes on the rich, are not subject to the whim of Democratic leaders in the legislature who may or may not agree with the bill on principle.

In that context, for example, Alzate’s support for existing legislative leadership makes her support for a tax hike on the rich effectively worthless, according to Brown.

It sends a message to lawmakers that they shouldn’t try to engage on these issues because the perfect is the enemy of the good.State Sen. Dawn Euer (D)

“It doesn’t do the people any good ... to say that you’re for taxing the rich and vote for, in your very first vote, leaders who will not let that bill come to the floor,” Brown said. “That’s not real change.”

Rather than solidifying progressive gains in Rhode Island, the Co-Op’s critics accuse it of serving as a vehicle to promote Brown’s gubernatorial campaign.

Brown, who mounted a short-lived campaign for the U.S. Senate in 2006, and lost a primary challenge against then-Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo (D) in 2018, has a clear, if narrow, path to the governorship in a race where he is already one of five major candidates.

By marshaling an army of door knockers on behalf of down-ballot Co-Op candidates who also support his gubernatorial bid, he can magnify his footprint in a way that maximizes his chances in a crowded field, according to his detractors.

“The Co-Op, above all else, is a vehicle to elect him governor,” the left-wing Rhode Island activist said.

Brown vehemently rejected suggestions that the Co-Op is designed to further his political fortunes.

“It’s really the opposite ... We want to use our statewide ticket, which is a pretty big operation, to elevate the message, elevate the candidates, elevate the fight,” he said. “Our mission is ... not just to win and elect a new governor and lieutenant governor, but elect a whole new government.”

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.