Progressives are selective in their silence over books banned by schools | George Korda

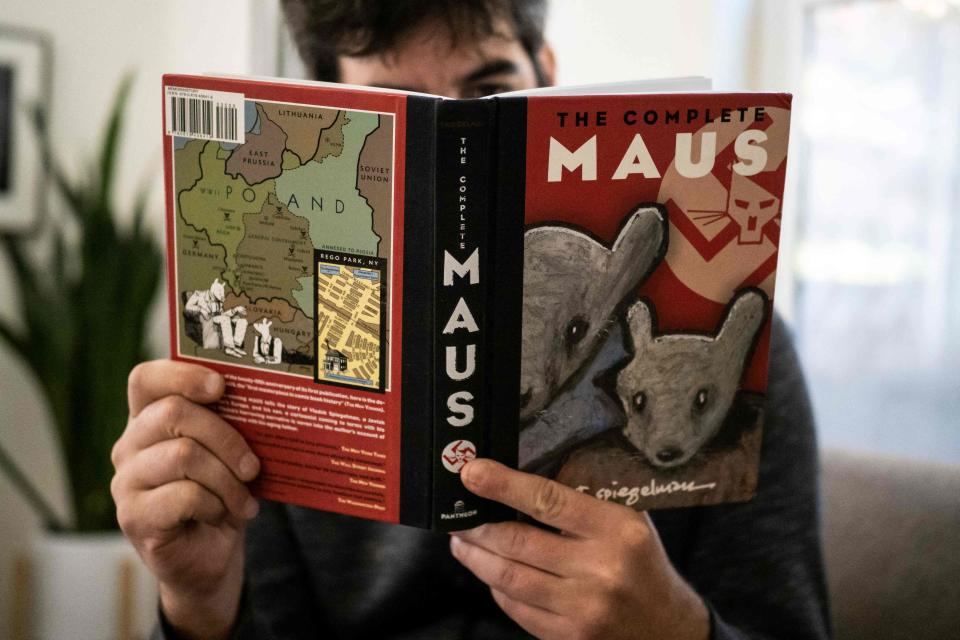

When the McMinn County Board of Education banned the book "Maus" from an eighth-grade language arts studies course in January 2022, it set off a storm of national derision and finger-pointing at Tennessee and at conservative efforts to have books officials labeled as inappropriate for children removed from school libraries and curricula.

But there is a much more muted response to “acceptable” book bans. Many “progressives” are silent when the targets are such books as the anti-racist classic "To Kill a Mockingbird," or Mark Twain’s "Huckleberry Finn,” often referred to as the Great American Novel.

"Maus" is a comic book, though there’s nothing comic about the subject: “A brutally honest depiction of one of history’s most horrifying tragedies, 'Maus' presents a story within a story, exploring the author’s tortured relationship with his aging father and recounting the chilling experiences of his father during the Holocaust,” says Penguin Random House.

The McMinn County Board of Education, citing curse words and a description of nudity, said no more "Maus" for eighth-graders. The outrage was palpable: “The Fight Over 'Maus' is Part of a Bigger Cultural Battle in Tennessee,” fretted the New York Times on March 4, 2022. On Jan. 7, 2022, Salon fumed, “’Orwellian": Tennessee school board sparks outrage with vote to ban Holocaust graphic novel 'Maus.' ” And it seems there was a desire for even seemingly unrelated issues to be related: “Here’s Why the 'Maus' Ban is a Queer Issue,” said the website intomore.com on Jan. 31, 2022.

Americans don’t know much about the Holocaust; as time passes, knowledge falls even further. NBC reported in 2020 that a survey found a “shocking lack of Holocaust knowledge among millennials and Generation Z.” Whether 'Maus' is the correct vehicle to inform eighth-graders is a subject for other discussions. The question, again, is: If this is a principle, why the pretty much thundering silence when the “censorship” isn’t from the political right?

What about 'To Kill a Mockingbird'? 'The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'?

Marshall University's Marshall Libraries monitors book bans. Among Marshall’s website information: “After parent complaints about the use of racist epithets in 'To Kill a Mockingbird'; 'The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'; 'The Cay'; 'Of Mice and Men'; and 'Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry,' the Burbank (California) Unified School District superintendent removed these titles from required classroom reading lists.”

Hear more Tennessee voices:Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought-provoking columns.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is a powerful fictional story set in the 1930s in a small Alabama town. In the book, a white lawyer defends a Black man against an unjust charge of the rape of a white woman. The story includes racially charged language common at the time.

Such offensive language is a reason for the canceling of "To Kill a Mockingbird" in multiple school systems. One item, which mentions Tennessee, from the Seattle Times is about a Washington school district decision: “Mukilteo School District removes ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ from required reading list.” Among other examples:

• “Wisconsin high school cancels production of 'To Kill a Mockingbird.' "

• “Minnesota school removes ‘Huckleberry Finn,’ ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ from curriculum.”

• “Mississippi School District Pulls ‘To Kill a Mockingbird.’

These actions didn’t result in the extensive national hand-wringing that followed McMinn County’s decision. An interesting note: in 2021, the New York Times asked its readers to vote to choose the best book of the past 125 years, announcing the winner in December of that year. The winner? "To Kill a Mockingbird."

Elected school board members' job is to settle disputes

There are books children should not see in their libraries and on their reading lists, and there are books that should be available to them, and adults are supposed to make those decisions. But adults are going to differ on which books are acceptable and which are not. When there’s a dispute, elected school board members represent the people’s interests. Not everyone is going to agree with their decisions, whatever decisions they make. But that’s why they’re there: to listen to the taxpayers who are paying the bills, and then make decisions. After that, board members can take the applause or the heat.

While these fights and others over such topics in schools as critical race theory and gender identity are escalating, an increasing number of parents are voting with their feet and leaving public school systems. The COVID-19 pandemic also has changed how children are taught, as described in an article in the Hill: “Nearly two million fewer students have enrolled in public schools.” Meanwhile, charter schools, private schools and homeschooling are seeing increased interest and participation.

A part of this maelstrom is that it isn’t reasonable for people who decry “censorship” and condemn the McMinn County Board of Education and others like it for their decisions to be silent or supportive when other systems take off the school library shelves books they say contain language that’s hurtful, offensive or inappropriate. That’s not principle; that’s personal preference.

A message of “We don’t want what we don’t want, and what you don’t want doesn’t matter” is, long-term, a self-defeating argument.

George Korda is a political analyst for WATE-TV, hosts “State Your Case” from noon to 2 p.m. Sundays on WOKI-FM Newstalk 98.7 and is president of Korda Communications, a public relations and communications consulting firm.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: George Korda: Silence on books banned by schools is selective