Project to eliminate mine waste at Belt Creek to be completed by end of summer

Belt, Montana, was built on coal.

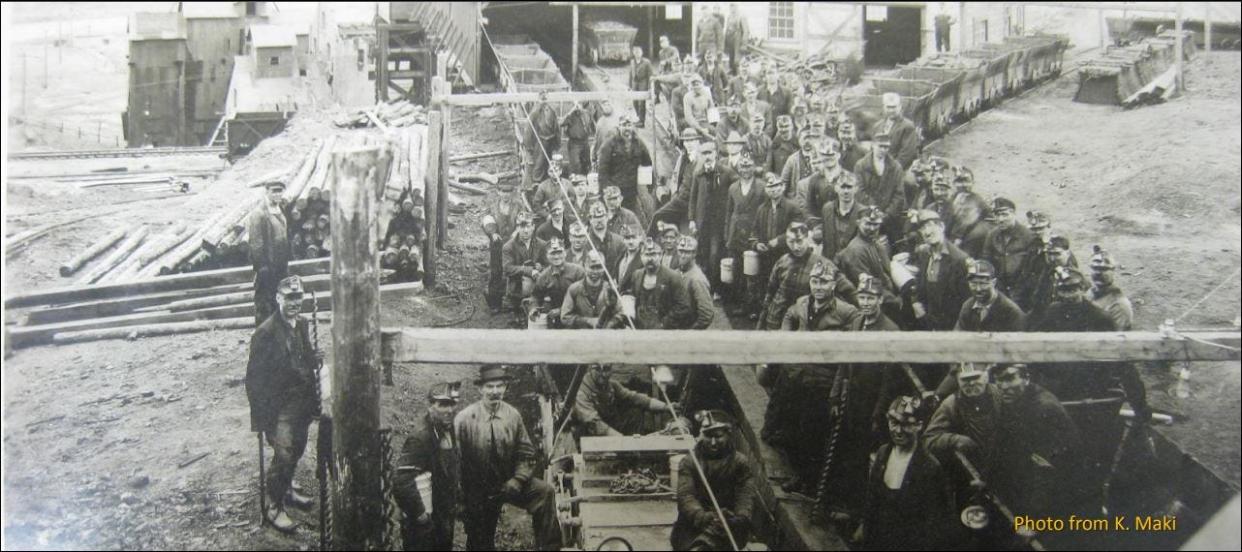

For 25 years men worked the coal mines ringing the small town east of Great Falls. The largest of these was the Anaconda Mine, which sat on the town’s western edge. The coal they harvested there was originally used to power the railroads, and later to fire the smelters of the Anaconda Copper Company, churning out the copper so desperately needed to electrify America and help the Allies win World War I.

By the time Belt mines played out in the mid-1920s, the Anaconda Coal Mine’s tunnels, shafts and drifts extended for miles. The main mine entrance sat on the hillside just west of town. It was an era that had little to no environmental regulation. It left behind a legacy of acid mine drainage that has fouled the waters of Belt Creek for nearly a century.

During the summer and on into the fall, when the flow of Belt Creek is at its lowest, the water running through Belt and north toward the Missouri River turns dark orange, a telltale sign of the high concentrations of iron and sulfuric acid draining into it. However, a $35 million project to capture, treat and halt the flow acid mine drainage into Belt Creek will soon be nearing completion – and with little to no direct cost to Montana taxpayers.

On Tuesday, Bob Flesher, Project Manager for the state’s Abandoned Mine Lands Program, updated Cascade County commissioners on the Belt Water Treatment Plant project. It’s been in the works for the past 11 years, but Flesher told the commissioners that he expects the Belt Water Treatment Plant will be completed by the end of this summer.

“I know a lot of people, especially in Belt, have asked when are you ever get this done?” he admitted. “We’re as close to getting it done now as we’ve ever been. I think the people in Belt are pretty eager to see it go in and not have that red water running down through town anymore. It will definitely improve the water quality in Belt Creek.”

When completed, the Belt Creek Water Treatment Plant will have the capacity to treat the more than 80 million gallons of acid mine drainage that each year.

The problem at abandoned coal mines like those in Belt stems from the presence of naturally occurring pyrite nodules within the exposed coal seam, some of which can be as large as four inches in diameter. As groundwater flows into the open mine workings, it comes into contact with these pyrite nodules and they break down, forming iron hydroxide and sulfuric acid. Water discharged from the mine becomes acidic, with a pH factor roughly equivalent to orange juice. The drainage also contains significant levels of dissolved metals such as aluminum, cadmium, nickel, and zinc.

“It’s not a very low pH, but it eats iron like there’s no tomorrow,” Flesher told the commissioners.

The acid mine drainage also kills aquatic life in Belt Creek and makes the creek’s water unusable for many common community uses. Flesher explained that treating the drainage coming from the old Anaconda mine is a relatively simple chemical process.

“It’s basically adding lime to the bad water to raise its pH,” he explained. “The sulfuric acid is neutralized, and the metals precipitate out. That will create a thick sludge. The sludge will be hauled out into big ditches where we let it de-water. Then the treated water will be released down a natural drainage to the north that flows east along the main road into Belt. It will then enter a culvert at the railroad tracks, then flow underground to be discharged into Belt Creek.”

According to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) the leftover sludge is relatively benign, consisting primarily of iron oxide and aluminum. It’s final destination has yet to be determined. It could be disposed of at a licensed landfill or deposited at a DEQ repository established near Belt.

A more intriguing possibility is that the sludge could eventually be reprocessed to extract “rare earth elements” critical to the production of everything from lasers and military equipment to magnets found in electric vehicles, wind turbines, semiconductor chips and consumer electronics such as iPhones. The process to extract these rare earth elements from mine waste is now only in the experimental stage but holds real promise for the future.

“All the coal everyplace has good levels of rare earth elements in them,” Flesher told the commissioners. “The technology to recover it is just getting started, but the Department of Defense and a lot of other federal groups are really interested in the rare earths because we have a big dependance on China for those elements right now.

According to the news agency Reuters, China currently controls 70% of the world’s production of rare earth elements. Chinese dominance in rare earth mining and processing is a deep concern for many countries across the planet.

The enormous costs of the Belt Water Treatment project is not due to the treatment process, it’s the cost of pumping millions of gallons of water several hundred feet uphill to where the treatment plant will be constructed on a field just north of U.S. Highway 87.

“Originally the plant was going to down in the bottom on what’s called Coke Flats,” Flesher said. “They did some geotechnical evaluation of that ground, and it didn’t have the stability that would be required to support the building and not have issues down the road. That’s when they decided to move the plant up the hill.”

The construction costs for the treatment plant, pump station, lift station, all the piping and a warehouse from which to work from is expected to be between $10 million and $12 million. The greater expense has been the creation of a $24 million endowment fund to cover the plant’s $500,000 annual operating costs with no charge to Montana taxpayers.

The push to clean up coal mine waste — not just in Belt Creek but at thousands of abandoned mine sites across the country — began in 1977 when Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). The Act established a new tax upon coal production in the United States, with money set aside to bear the cost of environmental mitigation at coal mines abandoned prior to 1977. For abandoned coal mines which operated beyond 1977, federal investigators attempt to find the responsible party to force them to pay the cost of environmental remediation.

The SMCRA applies a four-percent tax on all coal mined within the United States. The federal government keeps half of that tax to administer the law, and the other half goes to the states where the coal was produced. In Montana it amounts to more than $4 million each year.

While Montana's Abandoned Mine Land Program (AML) has successfully taken on close to 300 projects across the state since its establishment in 1980, the project at Belt Creek counts as one of the largest and most expensive it has ever attempted.

Technical aspects aside, the real benefits of the acid mine waste project at Belt will be realized when the creek returns to being the clear mountain stream it once was, more than a century ago.

This article originally appeared on Great Falls Tribune: Plant to clean mine waste from Belt Creek to open by end of summer