Projects from NC to Florida to California could help reverse declining bird populations

It wasn’t enough for Anders and Beverly Gyllenhaal to explain the research behind the arresting report in 2019 that said nearly 3 billion birds had disappeared across North America. The couple wanted to find out if anything could be done to reverse the decline.

What they report in their new book, “A Wing and a Prayer: The Race to Save Our Vanishing Birds,” is that people across the continent already have found ways to help birds and are looking for more. They range from the practical to the theoretical. Some are aimed at individual species while others could benefit the bird population as a whole.

Here are some of the projects included in the book.

In North Carolina and Georgia

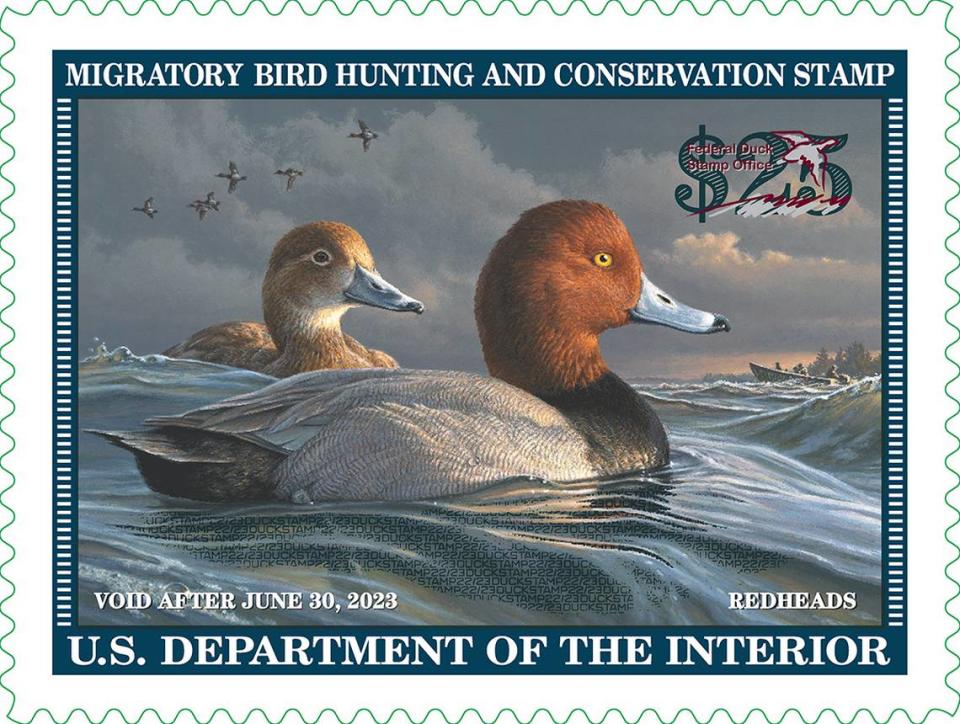

▪ Though it was incorporated in New York in 1937, the beating heart of Ducks Unlimited was on the North Carolina Outer Banks, on and around the peninsula in Currituck County known as Knott’s Island. There, publisher and philanthropist Joseph Knapp and his friends, including some of the nation’s wealthiest industrialists, pondered how to bring back the abundant waterfowl they had once hunted but which had been lost to a devastating years-long drought in the northern Great Plains.

Their solution: more habitat. The group has so far raised money to conserve nearly 16 million acres of land across North America. Owing to that work, numbers of game birds increased by 56% during the same period the 3 Billion Birds report found that other species had drastically declined.

▪ The red-cockaded woodpecker went onto the endangered species list even before the 1973 passage of the Endangered Species Act. It nests in old longleaf pine trees and likes them to be in the kind of open forest created by fires.

Two such areas of habitat are owned by the U.S. Army at Fort Benning, near Columbus, Ga., and Fort Bragg, near Fayetteville, which is becoming Fort Liberty. Into the 1990s, the Army prioritized weapons training over bird conservation, flagrantly destroying habitat and prompting the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to take Fort Benning officials to court to enforce protection laws. At Fort Bragg, USFWS went further, shutting down basic training.

All branches of the military now spend $79 million a year on endangered species conservation, including for the red-cockaded woodpecker. Fort Bragg marks the trees used by the bird and establishes a 200-foot buffer around some clusters of trees to limit human activity. Populations of the bird across the Southeast have recovered to the point that the Fish & Wildlife Service has proposed reclassifying its status from “endangered” to “threatened.”

▪ Passenger Pigeons went out of existence when the last one, a resident of the Cincinnati Zoo named Martha, died in 1914. A man in the North Carolina mountain town of Brevard, chief scientist for Revive & Restore, plans to bring them back through cloning sometime in the next few years.

On its website, the California-based company says it cloned the first black-footed ferret and last month announced the birth of the world’s second cloned endangered Przewalski’s horse foal. The group has enlisted the help of scientists in deciphering the genome of the Passenger Pigeon, figuring out how it differs from an extant pigeon species, subtracting the changes and breeding the bird in captivity in large enough numbers to repopulate the wild.

In Florida

▪ The White Oak Conservation Center in rural Yulee, Fla., focuses on protecting and propagating rare animals, including eight species of birds. Started in 1982 by the Gilmans, a paper-manufacturing family, it has been under the purview of Walter Conservation, owned by Mark Walter, owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

The center began working to save the tiny Florida Grasshopper Sparrow after its numbers inexplicably crashed in the early 2000s. After some heartbreaking trial and error in a captive-breeding program, workers at the center discovered the chicks they were hatching needed live bugs to eat from nearby fields in order to thrive.

▪ The Archbold Biological Station in Lake Placid, Fla., founded in 1941 by an heir to the Standard Oil fortune, is working to bring back the threatened scrub-jay, a native bird whose numbers dropped from about 40,000 in the 1980s to around 4,000 now.

Archbold electronically tracks scrub-jays to see how they use their space so they can make recommendations to improve their shrinking habitats and their breeding patterns.

In Louisiana

▪ Jane Zimorski, a biologist for the state Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, watches over captive-bred whooping cranes that have been introduced in the wild in the hopes they will mate and raise babies. Her current electronic surveillance system allows her to keep a constant eye on the birds, and she can tell by their movements if they are incubating eggs.

In California

▪ In the Sierra Nevada mountain range, wildlife ecologists are protecting spotted owl populations by keeping out an invasive competing species, the barred owl. In the late 2010s, researchers used recorders strapped to trees to locate barred owls and in three years shot and killed 64 of the birds, an upsetting but biologically necessary action.

Researchers continue to use bioacoustics in the Sierra to monitor the health of all the major bird species there.

In Kansas

The Hoy family has built a ranch outside Flint Hills where they raise cattle using “regenerative agriculture” practices that heal degenerated soil and build biodiversity. The cattle are a relatively small variety that doesn’t require hormones, antibiotics or grain. They feed on tallgrass that grew on the Northern Great Plains a century ago, which the Hoys coaxed back onto their acreage.

As native grasses returned to the Flying W ranch, so has other wildlife, including the long-missing Henslow’s sparrow.