How the promise of experimental gene therapy turned tragic for one Arizona family

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

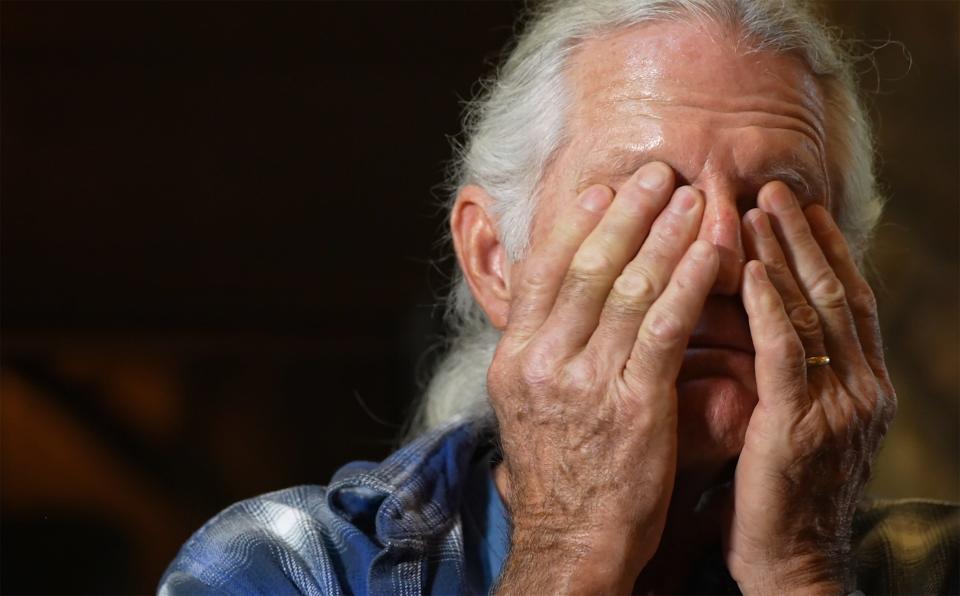

Paul Gelsinger has told the story of his son’s death before. But every so often he must revisit it. He must revisit Jesse.

He reflects on the places, the people, the events that changed his life forever. The doctor’s offices, the hospitals, the clinical trial that would make history.

He thinks back to when Jesse was a baby at their home in New Jersey, to the day they found him asleep on the floor, when nothing could wake him. He relives the 11-day stay at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania, a campus he and Jesse would return to one day under very different circumstances.

After that first stay, Paul got an answer to why Jesse, who had always been small and a picky eater, was sick. He had a disease, rare and serious, that meant his body was unable to process the byproducts of protein.

Jesse bounced back at first. He took pills, dozens of them, and adhered to a strict diet that limited his protein intake. He hated that diet, and sometimes he grew defiant, with disastrous consequences. As Jesse got older, after they had moved to Arizona, his defiance led to medical scares, experiences the family wasn’t sure Jesse would survive.

After that, he took new medications that allowed him to live a more normal life, ease his restrictive diet. Over time, Jesse made friends and got a job at a grocery store. He messed with his siblings and did what he had to do to get passing grades in school.

Then one day, when he was 17, Jesse’s doctor told the Gelsingers he had received a letter asking Jesse to participate in a gene therapy trial, one the researchers said had the potential to help other kids born with his disease.

Jesse said yes.

This was the moment when Jesse Gelsinger became a person whose story would be preserved forever in medical textbooks and law journals, newspaper reports and congressional records.

And it was the moment that stopped Paul’s world.

Because when Jesse was approved for the trial and finally flew by himself to Penn to undergo the procedure, his family didn’t know that he wouldn’t be coming back.

Jesse experienced a severe reaction to the treatment. Then he was gone.

***

As a human, you have about 20,000 genes, the building blocks of information you inherit from your parents that tell your body how to create you. Each gene carries instructions on how to create a certain protein, and those proteins ultimately form your body. If there are any mistakes in those genes, problems can develop.

The mistake that caused Jesse’s condition — ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, or OTC deficiency for short — involved just one gene out of those 20,000. The mistake meant that his body didn’t know how to produce one particular enzyme necessary to process ammonia, a normal waste byproduct created when we eat protein.

When you can’t process ammonia, it can build up to toxic levels in the blood. That means too much protein can be fatal for someone like Jesse with OTC deficiency.

That’s why Jesse’s disorder held so much promise to scientists: If they could find a way to get into the body’s cells and tell them how to make that one molecule, they could cure the entire disease.

And the idea of curing an entire disease by tweaking the genes — or, to start, a single gene — formed the foundation of an entire field of research known as gene therapy.

The field has grown steadily. Scientists are beginning to make headway on reversing conditions like blindness and sickle cell anemia. In January 2022, at a health care and policy conference, Danny Seiden, Arizona Chamber of Commerce and Industry president and CEO, joined experts from Pfizer, the Mayo Clinic and the Muscular Dystrophy Association to discuss the ethical implications and possibilities of gene therapy for people with rare diseases in Arizona, as well as its economic promise in a state where some leaders have ambitions of creating a bioscience hub.

In November 2022, the Center for Advanced Molecular and Immunological Therapies announced that, as part of a major funding effort, gene therapy will be coming to downtown Phoenix. The methods of gene therapy will be used in basic science aimed at better understanding the human genome, and that may eventually translate into human trials at the UA’s new research center, University of Arizona officials say.

“We’re really entering the cell and gene therapy phase,” said Dr. Michael Dake, senior vice president for health sciences at the University of Arizona. “The terms 'gene editing' and 'gene engineering' are very relevant and are going to be a big part of the future.”

But nearly 24 years ago, Jesse, who spent most of his life in Arizona, was the first person to die in a gene therapy trial. His death inspired lawyers and philosophers, doctors and researchers. He even inspired a hematologist who, in 2021, helped Arizona scientists propose some of the possible reasons behind rare reactions to some COVID-19 vaccines.

In that story, Jesse occupied a few lines. That’s often how it is. Jesse is the historical context behind the advances. The cautionary tale, the symbol of the stakes of human subjects research.

Despite that, despite Jesse’s sudden death, many of those closest to him still believe in the process of science, when it’s done correctly. They take comfort in the hope that what happened to Jesse may have paved the way for ethical science to create a better, healthier world.

But before all that was a family’s trauma, and the day Paul can’t forget.

***

The Gelsingers moved to Arizona in 1987, when Jesse was about 6 years old, and shortly after, Paul and Jesse’s mom divorced. Paul remarried, and he and his new wife, Mickie, together worked to raise six children in Tucson.

If Jesse stuck to his diet, he could still play and spend time with his siblings, run around outside. Jesse’s older brother, P.J., remembers riding dirt bikes, looking for make-believe treasure and occasionally tracking animals, collecting ants and shooting birds in the desert with their BB guns.

Even so, his younger sister, Mary, remembers Jesse taking medication several times a day, feeling “miserable” about his condition.

One of his other sisters, Anne, the youngest of the kids, remembers that too. Jesse was her annoying older brother, the one who couldn’t eat seafood, who had a little bit of an angry streak. The one who defended her from the kids throwing rocks at her on her way to school.

P.J. was a self-described nerd, but said Jesse wanted to be cool. He wanted to be popular and strong. He became obsessed with pro wrestling.

“He wanted to be this big guy who could take on anything and just didn't take crap from anybody,” P.J. said.

Jesse grew from a spunky kid into a rebellious teenager. He watched Adam Sandler movies, loved Rambo and Sylvester Stallone. He liked cats. He loved motorcycles.

And he really, really hated his diet. At times he did not follow it, with disastrous results.

The first time, when he was 10 and away from home, he fell into a stupor and was hospitalized for five days.

The second time, Paul came home and found him curled up on the couch. Jesse’s friend, who’d been with him, said Jesse had been vomiting uncontrollably. Paul rushed Jesse to the hospital, where he ended up intubated in intensive care, in a coma for five days.

They weren’t sure he would come back from this one.

But when Jesse woke up in his hospital bed, he motioned with his hand. Paul was standing in front of the TV screen, and Jesse wanted to see the show.

That sense of humor, palpable even in his weakest moments, blossomed as he recovered. It became even more apparent as he went on new medications. The meds were expensive, and during that incident, Paul had to fight with the insurance company over costs. Eventually, they allowed Jesse to live a more normal life.

Until he got the letter from Penn.

The researchers were asking him to participate in a gene therapy clinical trial aimed at his condition, and the prospect excited him and the family. One of the top universities in the country was working on his rare disorder, the same university where Jesse had been diagnosed as a baby.

Scientists had already lengthened the lives of mice with his disease, using a technique similar to the one Jesse would undergo if he participated.

At that moment in time, Jesse wasn’t doing it for himself. There was no guarantee his condition would be cured, and he wouldn’t see any direct effects in his own body. But he was hopeful that the research might one day mean that babies born with an even more severe version of his condition wouldn’t have to die, or suffer.

So on Jesse’s 18th birthday, on the June day in 1999 when he became eligible for the trial, he and his family flew to Pennsylvania.

***

Anne remembers that when they arrived, they visited with extended family. Jesse played volleyball with his cousins as they celebrated his birthday. Anne, a teenager herself, thought she wanted to go to the University of Pennsylvania for college someday.

On that trip, Jesse underwent a five-hour ammonia study to confirm his eligibility for the trial. Anne remembers falling asleep in a chair while she waited for Jesse and Paul to go over some paperwork. They read consent forms that, Paul says, they all believed adequately disclosed the risks.

After that, they toured more of Philadelphia, stopping at the famous statue of Rocky Balboa. Jesse loved seeing it, posed for a picture in front of it.

They took a brief trip up to New York City, visiting the FAO Schwarz store, then came home to Arizona.

A month later, they got the news: Jesse had been accepted into the trial. He would fly back to Philadelphia alone.

Everyone expected him to come back.

***

Paul had planned to join Jesse a week later, after the therapy was done. The most dangerous part of the trial, Paul initially thought, seemed to be the needle biopsy of Jesse’s liver that would occur after the infusion. Jesse would also experience flu-like symptoms during the trial, Paul said the doctors told him.

Paul figured Jesse would be able to handle that part just fine — Jesse had had the flu recently, in fact — but there was more to it.

Under the basic premise of gene therapy, scientists needed to insert corrected genetic material into cells. Viruses are really good at getting into cells, so researchers figured out that by using a modified virus — in Jesse’s case something called an adenovirus vector — they could insert whatever genetic material they wanted into cells.

The process takes advantage of biological processes similar to some vaccines, processes that were thrust into the spotlight because of COVID-19.

To combat the coronavirus pandemic, scientists developed two types of vaccines: mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna) and adenovirus vector (Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca). The mRNA vaccines directly give cells the instructions to make a little piece of protein that looks like the proteins on the coronavirus. Adenovirus vector vaccines do the same thing, but instead of RNA, they deliver DNA that contains those instructions, which are encased in a virus that has been modified not to cause disease.

In both cases, once your body recognizes those unfamiliar bits of protein, it triggers an immune response, mounting defenses that can protect you if you ever encounter the real thing.

In gene therapy, instead of sending instructions into cells to prompt an immune response, scientists aim to send instructions to correctly build a protein that the sick person’s body is building incorrectly, a flaw that causes disease.

Both vaccines and gene therapy have now saved or changed millions of lives, the former by preventing illness and the latter by curing disease or improving symptoms.

But Jesse’s trial took place in the early days of the technology. There would be so much more that would come to light, so many changes to what the technology looked like then. Some of those changes, those discoveries and advancements, would occur because of Jesse’s trial and the research it inspired.

Jesse’s family didn’t know that. Paul, who had previously worked in research and development at DuPont, thought he understood enough science to fully grasp what his son faced.

But he wasn’t given all of the information. It was information the Food and Drug Administration would later say he should have had.

***

The first part of the trial went as expected. Jesse spent eight hours immobilized on a gurney to receive the infusion. Not long after, he started to feel flu-like symptoms.

Paul and Mickie talked to Jesse on the phone.

They told him to hang in there. And there is a moment that is etched in Paul’s mind: when Jesse told him that he loved him.

“I got that back from my kid,” he said. “‘I love you too, Dad.’ Turns out those were my last words with my boy.”

The next day, the researchers called Paul. Jesse looked jaundiced, they said. Paul, recalling that jaundice had something to do with liver function, grew worried.

He boarded a redeye flight that night.

“It’s a very helpless feeling, knowing your kid is in serious trouble while you are a continent away,” Paul wrote in his original account of the incident. He was there by the following morning.

A neurologist came in to examine Jesse. She didn’t like the way Jesse’s eyes looked, she told Paul.

Jesse’s ammonia levels were rising. His oxygen levels were dropping. His lungs were shutting down. Eventually, the researchers put Jesse on a ventilator and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation unit, a machine that pumps and oxygenates blood outside the body.

The extended family that was in Philadelphia came to the hospital to be with Paul, and Mickie flew in. She caught the last flight into Philly before Hurricane Floyd shut everything down. They were shocked at Jesse’s appearance. He was unrecognizable due to his body’s swelling.

The researchers put them up at a hotel, but Paul couldn’t sleep. He returned to the hospital. Jesse didn’t look good. There was blood in the urine bag.

Mickie didn’t go to visit him, but went for a walk in the blustery aftermath of the storm. In the morning, they went back to the hospital, together.

Two doctors delivered the news: Jesse was no longer showing brain activity. His internal organs were collapsing. The doctors wanted to shut off life support.

Paul and Mickie collapsed into each other.

Paul asked for time with his family and for a brief service. He put his hand on Jesse’s chest. The hospital chaplain said a prayer commending Jesse for his sacrifice.

Paul knew he had to do what he thought was the right thing for his boy, no matter how much it tore at his heart. They had to let Jesse go.

Paul signaled to the doctors to turn off the machine.

Within two minutes, Jesse was gone.

***

Anne, who was back home in school, remembers it this way.

She remembers being in English class, fourth period. She’d just had lunch.

She knew Jesse was in a coma, on the other side of the country, but Jesse had been in a coma before. He’d been sick before. He always pulled through.

Another student came into the classroom and talked to her teacher. The teacher told Anne she needed to go to the office. Anne started to get up. They told her to take her things with her.

As she walked down the hallway, it dawned on her that they wouldn’t have taken her out of class, wouldn't have asked her to go to the office, to take her things, unless something really bad had happened.

That’s when she knew that Jesse was gone.

She took off down the hallway.

“I just started running,” Anne said.

***

Paul wanted answers about his son’s death. He wanted an autopsy.

The consent form Jesse had signed had discussed risks. They included possibilities like inflammation of the liver, an immune response from the body or an inability to receive a therapeutic dose of the virus in the future. The form mentioned that some of those risks could be life-threatening. But nothing in the consent form seemed “overly alarming” at the time, as Paul put it. He didn’t know that certain information had been excluded.

Paul did not believe the researchers had done anything wrong, not at first. It had been a tragic accident.

Then investigative reporters at The Washington Post, who were pursuing a story about the case, started unearthing problems the Gelsingers hadn’t known about.

Those were all problems that have been relevant over the past two decades and are still important today, according to legal and scientific experts.

A few months after Jesse’s death, Paul testified before the U.S. Senate as a health subcommittee discussed the oversight mechanisms in place for gene therapy clinical trials, and assessed where those mechanisms might be failing.

After that, the Gelsingers settled out of court with the Penn researchers. The family chose to give up the chance to see their concerns, their desires and losses, their hopes for the future of the research world, addressed in a public setting.

Instead, Paul, and so many others, have had to find different avenues to share Jesse’s story. To make sense of what happened to him.

Paul spent many years giving talks at conferences and universities, with researchers, scientists, judges and industry leaders.

He doesn’t do that much anymore. After a while, he had to stop. It was taking a toll on him, to keep going back to that part of his life so frequently.

But since then, many others have picked up where Paul left off, to make sure Jesse didn’t die in vain.

***

Robin Wilson is a law professor at the University of Illinois College of Law. Early in her career, she heard about Jesse’s case and her interest was piqued almost immediately.

But it wasn’t until she was standing at a photocopier with documents from Paul’s lawyers, documents from Penn whistleblowers who were worried about the project, that she realized the magnitude of what she was working on.

“Nobody even really understood what happened until Paul gave me his papers,” she said.

Wilson (no relation to James Wilson) wrote about what happened in a 2010 paper called “The Death of Jesse Gelsinger: New Evidence of the Influence of Money and Prestige in Human Research,” as well as in a book about bioethics and law. What had happened was this:

Jesse participated in a Phase I safety trial known as a stair-step trial, which means the doses went up with each set of patients who were enrolled. Jesse was the second patient in the sixth group.

The FDA later found that some patients before Jesse experienced reactions that should have put a “stop sign” on the research, per the researchers’ protocol and the consent form that Jesse signed. But the study continued anyway.

What’s more, the consent forms hadn’t mentioned that animals had died in earlier trials. Jesse hadn’t received the same dosage as they did. He got less, and it was a slightly different treatment. But a Penn whistleblower helped others realize that the animal deaths had been mentioned in an earlier version of the consent forms approved by the institutional review board.

And though Jesse’s ammonia levels tested outside the limits established by the experimental protocol, the researchers gave him the infusion anyway.

The researchers had been making changes on the fly, as the experiment proceeded.

One of the researchers behind the study, seemingly by his own admission, appeared to have a conflict of interest. James Wilson had been a founder at a company that would stand to benefit if the technology in Jesse’s trial succeeded (Robin Wilson, in her article, cites a Wall Street Journal story that valued his stake in that company at $13.5 million).

The FDA conducted an investigation and sent a warning letter to James Wilson, which stated that he had violated federal clinical trial regulations, and by 2002, concluded that he had failed to address those violations.

In the aftermath of Jesse’s trial, James Wilson wrote a “lessons learned” paper, a requirement as part of the settlement of the government suit if he ever wanted to return to human subjects research. The document was published in a scientific journal in 2009. Robin Wilson describes it as “mind-blowing.”

“Academic medicine is a competitive profession with the primary measure of success being recognition by your colleagues of your research accomplishments,” James Wilson wrote.

“I learned it is very hard to convincingly uncouple drivers for academic success from the incentives derived from potential financial gain. My conclusion is that the influence of financial conflicts of interest on the conduct of clinical research can be insidious and very difficult to rule out, as I have decided was the case in the OTCD trial.”

Robin Wilson thinks that while financial interests can motivate great scientific achievements and innovation, they can have a heavy price if they aren’t properly “firewalled.” That’s something that, at least from a legal perspective, she’s not confident has changed much since Jesse died.

“I think the hard question to be asking here now is, do you have the same kinds of money sloshing around, the same kinds of tethers between the researchers and the money or the outcome of that research? And who's watching?”

***

P.J. Gelsinger was always obsessed with technology and video games as a kid, and Jesse showed interest. Jesse thought “the coolest thing about you is your computer, man. I can play some good video games on there,” P.J. said.

When P.J. was in graduate school at the University of Arizona, he developed a scientific invention of his own.

It was a device surgeons could use for early detection of ovarian cancer while patients were in surgery, essentially a small handheld microscope that doctors could deploy in real-time.

But when it came time to try to commercialize the device, no companies were interested. So the device now sits on a shelf. P.J. still holds the patent.

This, he says, is the reality of working as a scientist in corporate America.

Take, for example, the Bayh-Dole Act. In 1980, the legislation allowed small businesses and universities to patent, license and profit from their inventions. As a result, there are now entire divisions of universities responsible for handling “technology transfer,” or the process of marketing scientific advancements.

In 2021, an advocate for the Bayh-Dole Act wrote an essay praising the obscure law’s role in the creation of a COVID-19 pill. Skysong, Arizona State University’s tech transfer center, says on its website that more than 100 spinout companies have raised over $600 million in venture capital. And the University of Arizona’s commercialization arm, Tech Launch Arizona, reported a record number of inventions in the summer of 2022.

But P.J. says that system doesn’t always leave room for researchers to explore ideas that aren’t as potentially lucrative. It doesn’t provide a safety net for failure. Instead, it means a lot is riding on scientific ideas that get funding, because researchers and universities are under immense pressure to ensure that their investments pay off.

Paul thinks the Bayh-Dole Act should be amended to better separate financial conflicts of interest from research interests. Even ethical people are not impervious to the influence of money, he says. And he thinks that influence may be continuing to corrupt some research.

At Penn, James Wilson’s lab continued to work on gene therapy technology. His influence grew over the years, and after partnering with multiple startups, Wilson is back in a leadership position at Penn’s Gene Therapy Program.

Paul, meanwhile, has been following the University of Pennsylvania student journalists who, in late 2021, reported that Penn’s gene therapy program was suffering from a toxic workplace under James Wilson.

Those stories are still unfolding, but their themes resonate with P.J.’s reflections on what happened to Jesse. He acknowledged that the economic and legal incentives of science can lead to a lot of good. Events like Jesse’s death are rare, and a lot of safe and effective medical devices, treatments and procedures exist because the system is “generally efficient toward mitigating tragedy.”

But the Gelsingers have to hold that fact on one hand, and a deeply personal and tragic event on the other.

“The fact of life is that capitalism is dehumanizing. It's just a fact. The economics of our country are dehumanizing. It knows nothing sacred,” P.J. said. “Because whatever is good for business is what gets done. If it’s not profitable, it doesn’t happen.”

***

Despite everything that happened to Jesse, the Gelsingers believe in science.

In the face of a pandemic, even as some — including some extended members of the family — used Jesse’s name to argue against coronavirus vaccines, Jesse’s family got vaccinated.

“They actually learned from my brother's case in developing the COVID vaccine,” Anne said. “And that's the pinnacle of what my brother would've wanted.”

Anne also noted that her brother had a rare disease and was immunocompromised. That means he needed scientific advancements to find treatments. It also means that if he’d been alive during the pandemic, anti-vaccine conspiracy theories would have put his life in danger.

So to anyone who helped spread misinformation about vaccines or mistrust in science, Anne says simply: “My brother would've found you so annoying.”

That doesn’t mean they are unquestioning. Paul reads a lot of scientific literature. He asks his doctors lots of questions before medical procedures. And he, along with others in his family, wants scientists to pursue their work ethically, for the laws governing that work to be improved, and for researchers to fight misinformation and conspiracy theories by showing, in every experiment and trial, that they are deserving of trust.

“There's just going to be a segment of the population that just chooses to ignore the good that has come out of this,” Mary said. “That sounds crass because obviously he (Jesse) died, right? That's not the good part of it. But the positive changes that have happened afterwards — or even the good of him wanting to be in the trial. And the potential benefits for future generations.”

***

Mary, like her family and many others, sees Jesse’s decision as a selfless act of bravery, one she’s not sure she would have the courage to take upon herself. But she recognizes that many people like Jesse, particularly those who are faced with rare and life-threatening diseases, often make that choice, and participate in trials that help the advancement of science for everyone.

She now works in clinical trial regulation, helping ensure that clinical trials are as safe as they can be. She says they’re a lot safer today because of Jesse.

But Mary also acknowledges that there are legitimate reasons why people hesitate to trust science and scientists. And she thinks there are concrete ways that the scientific community can continue to improve to combat that mistrust.

First, clinical trials need more diversity to create better, more representative treatments and therapies. To do that, researchers need to persuade more diverse populations to participate.

Second, people need to be better educated and informed from an early age about the process of science. And scientists need to use clearer and more transparent language to describe their work.

And third, guardrails need to be improved to ensure researchers disclose their financial interests.

Mary believes there’s room for redemption, and for mistakes in science, but that appropriate acknowledgment of situations where researchers cut corners would go a long way in helping people trust scientists who are doing things the ethical way every day.

Paul still wonders why Penn puts its trust in James Wilson and allows him to remain in leadership, given that media outlets have reported on employees who describe the negative workplace culture he created. Still, Paul knows he may never get that answer in this specific case, as neither the university nor Wilson’s program has faced permanent consequences.

Representatives for the gene therapy program and Wilson did not comment after repeated requests by The Arizona Republic.

Paul and his family are now focused on the hope of the future: safe and ethical science, potentially groundbreaking advancements made possible by their son and brother.

And healing from the personal trauma they went through. Mary says they couldn’t imagine going on living for a while, through the pain, grief, confusion, anger and betrayal.

But the trajectory of all their lives changed because of Jesse. Over time, they have tried to find peace in that.

Paul says he has become more appreciative of the lessons his son taught him. Some of those are intimate and tender. A few years ago, he got a tattoo of a flying squirrel, a character that represented the wrestling federation Jesse wanted to create: BLWF, or “Bunch of Losers Wrestling Federation.”

“He was just animated. He was a great kid,” Paul said. “He showed me some things in life.”

Those are the memories Jesse’s family holds close, the ones that don’t usually appear in textbooks and articles. The weight behind Jesse’s sacrifice.

“Doing this one thing has changed medical history,” Mary said. “I hope for the better.”

***

In 1999, the New York Times Magazine began its description of Jesse’s death with his funeral, which took place on Mount Wrightson, a little over an hour outside Tucson.

It described prickly pear and ponderosa pine, the beautiful and distinctive landscapes of Arizona, as though Jesse’s spirit, laid to rest on the mountain, was inextricably linked to this place.

But no matter where his family went, Jesse shaped the rest of their lives long after his death.

Paul and his wife, Mickie, split their time between Tucson and a home on another mountain outside Tucson, Mount Lemmon. They acknowledge that they can live the way they do mostly because of the settlement they received from the Penn researchers, who are still working in the industry, and whom Paul has not forgotten.

Gene therapy research — human subjects research of all kinds — continued.

In Paul and Mickie’s bedroom, on a dresser, sits a row of biology textbooks in which Jesse’s name is mentioned.

P.J. lives in California. Mary lives in Tucson.

Anne lives in Philadelphia. After high school, a not-so-pleasant experience colored by prying questions from classmates, she attended the University of Arizona. Her dream of going to Penn, she says, died with Jesse. Her experience of higher education has gone hand-in-hand with the gravity of her brother’s case.

“I can't go anywhere around a college campus with biology students,” she says. “There's always somebody that knows.”

But she’s also come to terms with the loss. When something traumatic happens at such a young age, she says, you have to do the math. You have many more decades to continue building your life. And you have to do your best to grapple with grief every day, while moving on alongside it.

She’s watched the research progress. In 2012, gene therapy cured a girl named Emily who had leukemia. That, she says, was exactly what her brother wanted. It took a long time, and she had to be patient, but she’s seen it happen.

When she heard about Emily, she decided to go to Penn’s campus. She took flowers to the famous LOVE statue and put them on the ground behind it. She walked around.

When she came back, someone had taken the flowers and separated them, put them onto the statue in its nooks and crannies.

She took it as a sign that things were going to be OK.

Republic health reporter Stephanie Innes contributed to this article.

Melina Walling is a general assignment reporter based in Phoenix. She is drawn to stories about interesting people, scientific discoveries, unusual creatures and the hopeful, surprising and unexpected moments of the human experience. You can contact her on Twitter @MelinaWalling.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Experimental gene therapy turned tragic for Jesse Gelsinger's family