Property tax limits, state-owned land: What's to blame for Salem's budget deficit?

What led to Salem's budget deficit remains a hot topic with less than two weeks to go before residents decide on a payroll tax.

City leaders have pointed to a litany of factors leading to the projected $11 million shortfall, including Oregon's property tax system, which has not kept pace with Salem's growth and the number of tax-exempt properties within city limits.

Many opponents of the employee-paid payroll tax on the Nov. 7 Special Election ballot blame the city's spending habits on what they call a bloated bureaucracy.

In a Statesman Journal poll on the payroll tax and in city budget discussions, critics called for across-the-board cuts of all city jobs, eliminating homelessness services, reducing police and fire budgets and cutting "luxuries" like the library.

A recent study of other cities in Oregon indicates Salem is not alone in its budget woes. Eugene, Corvallis, Gresham and other municipalities are facing deficits and looming cuts.

As part of the Statesman Journal's ongoing series on the payroll tax, which taxes people working in Salem .814% as early as July 2024, here's an examination of those claims.

$7.25 million revenue lost due to state-owned land in Salem

Property taxes are the primary source of funding for Oregon cities for general services, including police, fire and parks.

In Salem, property tax revenues for the fiscal year that ends June 31, 2024, are budgeted for $84 million.

The property tax collections are deposited into the city’s General Fund and, according to city records, cover 45% of general fund expenses and 77% of the cost of providing police and fire services.

Not every property in Salem is required to pay taxes.

Schools, churches, nonprofits and government facilities are among those exempt. In the 2022 tax year, tax-exempt properties accounted for $5.5 billion in real market value in Salem. All properties, regardless of tax status, receive the same public safety response.

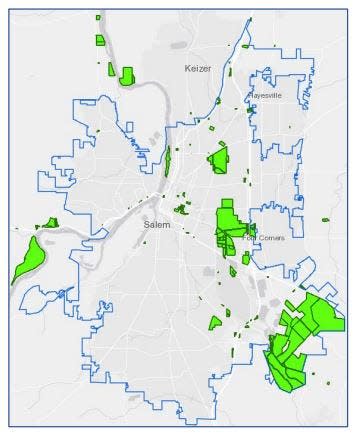

The biggest non-city-exempt property presence in Salem is the state of Oregon, with about $1.65 billion in real market value.

"As the state capital of Oregon, the concentration of state-owned properties requires services be provided, these services are effectively subsidized by other taxpayers," city staff said in a September report on property taxes.

In some capital cities, including Olympia, Washington, state government provides payment in lieu of taxes to help cover some of the services that would have been paid with property taxes.

Salem has no such agreement, although the idea has been discussed in the past.

Staff estimated state-owned property accounted for 8% of land within Salem's city limits. If taxed, those properties would generate $7.25 million a year.

Oregon voters placed limits on property taxes

Blame also has been put on changes voters approved that made Oregon's property tax system less flexible for cities.

City leaders, including City Manager Keith Stahley, have long-talked about property tax measures passed in Oregon in the 1990s that led to many cities' budget troubles.

Before 1990, local governments had more leeway to charge the amount needed for the next year's operations. But that year, Oregon voters passed Measure 5 to limit taxes local governments could charge.

Measure 50 in 1997 further limited this taxing power. The measure created a permanent rate that local governments could assess, essentially freezing them in time. Salem's rate is set at $5.83 per $1,000. Eugene, which has a similar population, is set at $7.01.

"The measure also limited growth in a property’s assessed value to 3% annually," city staff said in the report. "When a jurisdiction’s expenses grow at a faster rate, property tax revenue can not keep up with these expenses."

The measures "fundamentally changed Oregon's property tax and public school funding systems," Mark Henkels, Western Oregon University professor for politics, policy and administration, wrote in the Oregon Encylopedia.

"According to the October 2006 issue of Oregon Business, the first sixteen years of Measure 5 and Measure 50 reduced local revenues by $41 billion," Henkels wrote.

After Salem City Council voted 5-4 in July to implement an employee-paid payroll tax, Oregon Business & Industry, a statewide chamber of commerce and trade association, launched the effort to refer the tax to voters.

The group gathered enough signatures to send the issue to the November ballot.

Preston Mann, a Salem resident and political affairs director for OBI, said the group recognizes the budget constraints that cities across Oregon face.

"We are particularly sympathetic to the unique challenges Salem faces due to the significant amount of state property in the city," Mann said.

"However, that does not excuse the Salem City Council's decision to pursue a costly, complicated and convoluted payroll tax that will cost hardworking residents over $500 annually," he said.

Property taxes are not on the ballot — the payroll tax is, Mann added.

Several Oregon cities face similar budget shortfalls

Salem leaders asked consulting firm Moss Adams to conduct a review of other Oregon cities' financial conditions. to provide additional context to the city's budget discussions.

The review of Eugene, Gresham, Hillsboro, Bend, Springfield and Corvallis found budget challenges in all six cities.

"As expected, the review of peer cities’ financial conditions indicates that the state’s structural problems with property tax funding, created by Measures 5 and 50 in the 1990s, have reached a point of critical concern for municipalities," Moss Adams staff wrote in the review.

"Cities throughout the state are figuring out how to afford additional services demanded by growing communities while revenues are constrained by state law," Moss Adams said.

All cities studied faced current and projected structural deficits, and some would have faced bigger shortfalls were it not for one-time American Rescue Plan Act funds and land sales.

According to the report, an $8.3 million general fund deficit looms in Eugene in Fiscal Year 2025. Reductions in Eugene's 2023-2025 budget included $18.6 million in ongoing service reductions and $4.3 million in one-time reductions. At a department level, these cuts entailed $3.7 million from police and $6.6 million from the library and cultural services.

If Eugene does not adopt new revenue strategies in the coming months, the city will soon have to implement "even sharper service reductions and continued layoffs," according to the report.

Gresham also faces a growing deficit, especially in light of a failed safety-focus levy that residents voted against in May. Their fiscal year 2024 deficit is $8.2 million. In fiscal year 2026, it's expected to be $15.2 million. The city cut 31 positions in the past year and is considering trying again with a public safety levy and increasing operations fees.

For questions, comments and news tips, email reporter Whitney Woodworth at wmwoodworth@statesmanjournal.com, call 503-910-6616 or follow on Twitter at @wmwoodworth

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Salem budget deficit: Property tax limits, state-owned land to blame?