Prosecutor seeks to free Missouri prisoner who judge says is innocent of 1990 murder

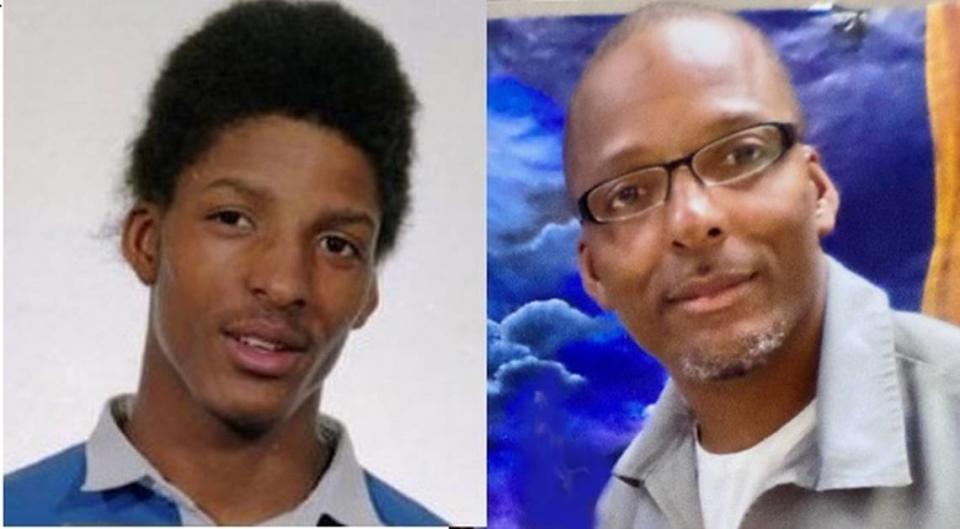

The St. Louis Circuit Attorney’s Office has filed a motion seeking to free Christopher Dunn, who prosecutors say has spent more than three decades behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

Evidence proves Dunn, 51, is innocent and “should not remain in custody a day longer,” a special assistant to Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner wrote in the motion to vacate Dunn’s convictions. They are asking the courts to “end this injustice.”

Arrested at age 18, Dunn was convicted during a two-day trial of first-degree murder and other crimes in the May 18, 1990, fatal shooting of a 15-year-old boy named Ricco Rogers in St. Louis. His conviction was based on the testimony of two boys, 14-year-old DeMorris Stepp and 12-year-old Michael Davis, both of whom have since recanted and admitted they lied at trial.

For months, lawyers and activists have urged Gardner to seek to overturn Dunn’s convictions. His case has drawn national attention for the legal conundrum in which he has been trapped: Dunn remains incarcerated at the South Central Correctional Center in Licking despite the fact that a judge, William Hickle, in 2020 agreed a jury would now likely find him innocent.

With the recantations and evidence of Dunn’s alibi, Hickle wrote, he did not believe “any jury would now convict” him.

Hickle declined to free Dunn, though, because he is not on death row. Legal precedent in Missouri restricts freestanding innocence claims — ones made without constitutional violations — to prisoners who have been sentenced to die. It meant Dunn would have been better off had he been awaiting execution, as opposed to his sentence of life in prison plus 90 years.

In the motion, Gardner’s office called that legal limit inexplicable.

“We have an ethical duty to work to correct this injustice,” Gardner, who is resigning June 1, said in a statement Monday. “We are hopeful his wrongful conviction is set aside for the sake of Mr. Dunn, his family and the people of the City of St. Louis.”

Dunn’s legal team, including attorneys with the Kansas City-based Midwest Innocence Project, thanked the circuit attorney’s office for their efforts. In a statement, they noted Missouri is the “only state” that limits innocence claims based on a prisoner’s sentence.

“Until the legislature changes the law, only a prosecutor can petition a court to free an innocent defendant sentenced to anything less than death,” Dunn’s attorneys said.

The state’s witnesses recant

The shooting that sent Dunn to prison unfolded at night outside 5607 Labadie Ave. in the city’s Wells-Goodfellow neighborhood.

In their motion, prosecutors laid out their evidence of Dunn’s innocence.

For one, no physical evidence tied him to the killing.

The first witness recantation came in 2005, when Stepp signed an affidavit saying he committed perjury when he testified that Dunn was the shooter. He identified Dunn because he did not like him and because the police told him to do so, he said.

A prosecutor also cut Stepp a deal in an unrelated robbery case in exchange for his testimony. He ultimately got probation instead of a potential prison term of 30 years to life.

“I’m willing to come forward after all these years, because my conscious has been eating a way (sic) at me for all these years,” Stepp wrote in an affidavit, adding that he was a scared kid who didn’t know better. “I just want to do what is right now and tell the truth.”

Meanwhile, Davis provided a reason for his lies: He and Stepp were Bloods gang members, and he said it was “rumored” that Dunn was part of the rival Crips in their neighborhood — an accusation that Dunn’s wife has called false. Prosecutors also note that no gang ties were brought up at Dunn’s trial, which was devoid of a motive.

Davis was initially uncertain about his identification, but detectives showed the pre-teen “gruesome photos of Rogers’ corpse,” according to Gardner’s office. They pushed him.

“Are you gonna let them do this to your friend?” he recalled the police telling him.

Adding to the pressure, detectives also had Rogers’ mother call Davis. She cried, asking him to help get this “monster” off the streets.

Judge: Dunn is innocent

When Dunn’s attorneys took his new evidence to court in 2018, Dunn’s wife thought they brought far more to the table than what prosecutors used to convict him.

It was so apparent that after the hearing, she said, a sheriff’s deputy apologized to Dunn’s mother.

Their evidence included testimony from a prisoner who said he overheard Stepp admit he didn’t know who killed his friend, as well as two of Dunn’s friends who said they were on the phone with him around the time of the murder.

One of those friends, Catherine Jackson, who was 16 at the time, said she told a public defender about the call, but that her mother did not want her to testify at a murder trial.

“I remember Chris Dunn was happy and acting normal,” Jackson wrote in a 2016 affidavit, later adding: “It has always bothered me that this boy … was arrested for a murder he supposedly committed on the night I was talking to him for almost an hour on the phone.”

Another witness, Eugene Wilson, has swore that it was so dark, there was no way Stepp or Davis could have seen the shooter.

During Dunn’s prior attempts to overturn his convictions, the Missouri Attorney General’s Office has argued he is guilty. The office called the recanting witnesses “repeat criminal offenders” — Stepp is doing life in Missouri for killing a girlfriend and Davis did not testify at the 2018 hearing because he escaped from a California drug treatment center, making him a “fugitive from justice.”

The AG’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Gardner’s effort to free Dunn.

Dunn’s mother and sister have also testified he was home around the time of the shooting.

In a call from prison, Dunn previously told The Star he was outside with his mother, uncle and siblings when they heard the gunshots three blocks away. His mother said, “these fools out here shooting, let’s go,” and rushed them inside.

After he heard evidence at the 2018 hearing, Judge Hickle was convinced.

“Coupled with the evidence in the record that (Dunn) had an alibi, this Court does not believe that any jury would now convict Christopher Dunn under these facts,” he wrote.

But in denying Dunn’s petition, Hickle cited an appeals court decision in Lincoln v. Cassady, which lawyers say is a significant barrier to freeing innocent prisoners in Missouri. It was in the case of Rodney Lincoln that the appeals court in 2016 said the state supreme court had not recognized actual innocence as a reason to free a prisoner who was not facing death.

The ‘Missouri 3’

Dunn has dubbed himself a member of the “Missouri three” — a group of prisoners who, while they served time in separate cases, had the support of public officials in their fight for exoneration.

The other two, Lamar Johnson and Kevin Strickland, have been exonerated through the legal path Gardner is now taking to free Dunn.

Johnson spent more than 28 years in prison for a murder he did not commit in St. Louis. Strickland, whose case was the focus of a Star investigation, spent more than four decades in prison for a triple murder in Kansas City that he did not commit.

Earlier this month, Gardner announced she will resign June 1.

She agreed to step down after cutting a deal with lawmakers who agreed to no longer pursue legislation that would have allowed Missouri’s governor to strip prosecutors of their ability to handle violent crimes.