Protests hit U.C. Berkeley over display featuring U.S. colonizers in Philippines

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

University of California, Berkeley, students, faculty and alumni, including those of Filipino descent, are protesting an exhibit that they say depicts Filipino history and scholarship through a racist lens.

Members of the university’s community have been speaking out against the exhibit at the university’s main library, which aims to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the department of South and Southeast Asian studies.

They say a portion of the exhibit — which features the works of several white male Berkeley scholars such as David Barrows and Bernard Moses, who championed U.S. colonization of the Philippines — perpetuates racist beliefs while decentering those of Filipino descent.

Though a 300-word addendum has been added to the exhibit this month, the school’s student government, along with several other campus organizations, hosted a protest Thursday before the conclusion of October’s Filipino Heritage Month. The groups indicated that the addendum is insufficient, demanding an apology from the school.

“What is the right thing to do? To work with communities that are directly impacted, and to work collaboratively to have an exhibit more stakeholders can be proud of,” Alex Mabanta, who spearheaded the rally, told NBC Asian America. “There’s been no forum for direct community input.”

Janet Gilmore, a campus spokesperson, said in a statement that the university will “continue to meet with members of the school community.” In reference to the addendum, she wrote that the library had made modifications to the exhibit, but did not offer an apology from the school.

“While individuals such as David Prescott Barrows have a clear legacy of racism towards Filipinos, Black people and Indigenous peoples, they and their work remain part of Berkeley’s history,” she said in the statement. “And for that reason we must exercise extreme care, caution and sensitivity when presenting their work and discussing their legacies.”

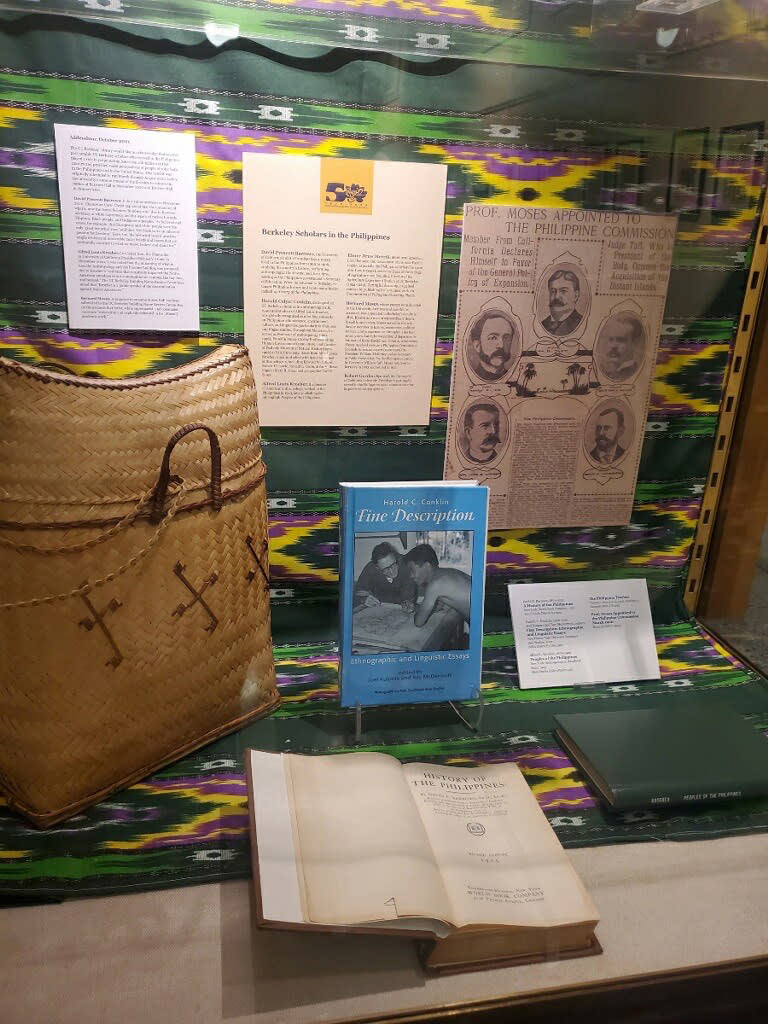

The display case entitled “Berkeley Scholars in the Philippines,” had originally been presented with the details and works of school administrators who supported colonization, including Alfred Louis Kroeber, Robert Gordon Sproul, Moses and Barrows.

Absent from the display was proper criticism of the men’s harmful legacies, particularly as the university had already begun to strip some of their names from buildings last year, several faculty members noted.

Barrows, who was a faculty member at the university for decades in the early 1900s, served as superintendent of schools in Manila while the United States had been occupying the Philippines. While in the role, he instituted the usage of his own textbook, “A History of the Philippines,” as the standard for schools in the country. The textbook is included in the display.

Barrows, who had expressed that Filipinos had “an intrinsic inability for self-governance” and were an “illiterate and ignorant class,” had championed the superiority of English over native Filipino languages, Joi Barrios, a lecturer of Filipino language at the university said. In his reinforcement of feudal, colonial and pro-imperialist values, Barrows left a lasting, damaging legacy in the Philippines, she explained.

“The moment you privilege English as the language of education … You come to accept colonization, and you come to think of your culture as inferior to the culture of the colonizers,” Barrios said. “Then you kind of accept the ‘benevolent assimilation’ myth that you were colonized, because you deserve to be colonized.”

Among other problematic elements in the display is an old newspaper article announcing Moses’ appointment to the Philippine Commission. The commission, which was established by then-U.S. President William McKinley and made up of white men, operated as a legislative and, to a lesser degree, executive power in the Philippines in 1900.

In response to the display, which they say included “almost no discussion or representation of communities from the Philippines, including Berkeley scholars from the Philippines,” the school’s student government passed a resolution last week to condemn the exhibit.

In the resolution, the group demanded that the university not only “acknowledge and apologize for the harms it perpetuates in surfacing the colonial period from the colonizers gaze,” but also advocate for recognition and celebration of October as Filipino American History Month. It is also asking for commemoration of Oct. 25 as Larry Itliong Day, uplifting the work of the legendary Filipino American labor organizer. The student government also called for further commitment to campus resources and academic initiatives, including a Philippine studies program, to create a more inclusive environment for those of Filipino descent.

Catherine Ceniza Choy, a tenured Filipino American professor of ethnic studies who said she was not consulted for the opening of the exhibit, said the display was particularly alarming considering the awareness around Barrows’ and the widely discussed renaming process that had taken place.

“What happened here at this exhibit is yet another example of the persistence of U.S. national amnesia about colonialism in the Philippines and the violence of that colonialism,” she said.

While information on the white scholars is provided in the display, another table, which contains the works of Choy and Karen Llagas, another lecturer at the school who teaches Filipino language, among others, is given no such background and sits in a separate area.

Choy pointed out that the intention of the exhibit is to celebrate scholarship in the past 50 years. Not only were the works displayed largely pro-colonialist, she said their scholarship preceded the 50 years, which further erases the achievements of the many academics of Filipino descent who have come from the university.

“There’s a way in which these representations also perpetuate how white American men specifically are historical agents and actors and that the Philippines’ peoples and Filipino Americans in the diaspora — we are of the past. We are not dynamic. We are not actors who are central in this history,” Choy said, pointing out that Berkeley has no shortage of contemporary scholars of Filipino descent.

Choy, who said she was only contacted about the exhibit after it had been opened to the community, said the addendum felt like an afterthought.

Though the portrayal of the Philippines is offensive and inaccurate, it’s more so a reflection of an American colonial mentality that is embedded into U.S. education, Llagas explained.

“It’s not to put the blame on the people who curated this exhibit. It’s kind of to shine a lens on what it is that they’re operating in. what culture and what academic climate they’re operating in,” she said.