PSD students of color are twice as likely to be disciplined as their white peers

Poudre School District students of color were disciplined, suspended and referred to law enforcement at disproportionately high rates during the 2019-20 school year.

Students of color were 1.7 times more likely to have at least one discipline event than white students, 2.3 times more likely to get an in- or out-of-school suspension and 2.2 times more likely to be referred to law enforcement.

PSD's most recent monitoring report, released annually to evaluate the district’s progress toward its goals, recognized the district had "clear disproportionality in 2019/20 discipline data by ethnicity" and that the patterns were "evident in past years as well."

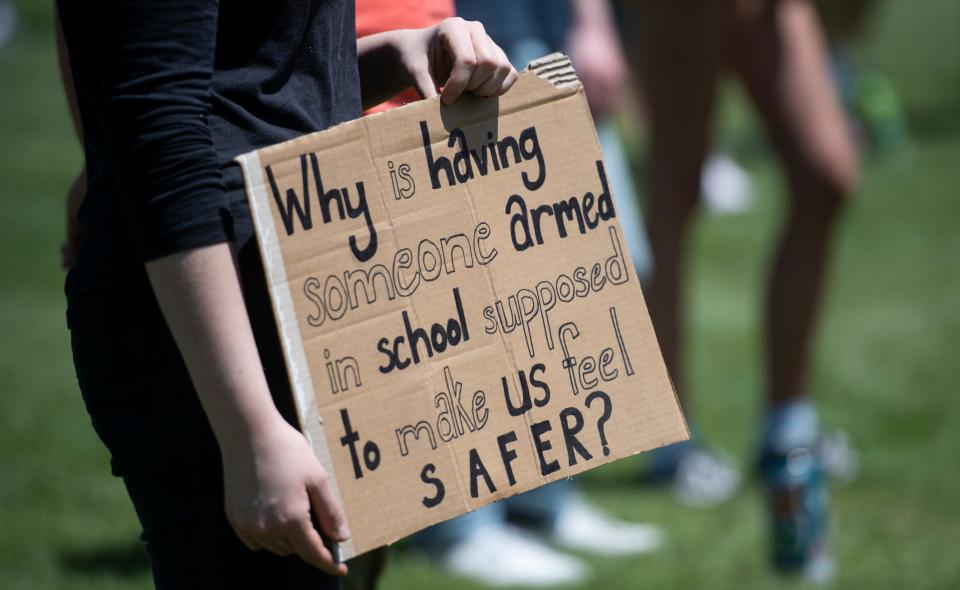

Related: Fort Collins students rally for change to Poudre School District race, policing policies

The numbers are even more disparate when broken down by specific ethnicities.

For example, Hispanic students — who make up 19.3% of PSD's student body — account for 31.5% of discipline cases, 38% of suspensions and 34.1% of students referred to law enforcement.

Black students — just 1.2% of PSD's enrollment — make up 2.3% of students who have had at least one discipline event, 2.8% of suspensions and 5% of students referred to law enforcement.

This was the first year discipline data was included in the district's monitoring report, something that Scott Nielsen, assistant superintendent for secondary schools, said the district has been working toward for years.

Carolyn Reed, a director on the district's board of education, said she had been actively seeking this information for years in order to see if the district mirrored national trends that showed disparities in students who were disciplined.

“Just like every other district, we do have issues in the way discipline is handed out,” Reed said. “And I think a lot of districts are looking inward and trying to understand what their data is saying, what they need to work on.”

Now that the district has made the data public and committed to a goal of reaching racial parity in discipline numbers and academic outcomes, the question looms: What changes will be made?

Last summer following the death of George Floyd and the emergence of Black Lives Matter protests nationwide, some Fort Collins and PSD community members called on the district to commit to an anti-racist curriculum and not renew its contract with Fort Collins Police Services for school resource officers, among a number of other things.

The district made a statement in June 2020 declaring its commitment to create an equity framework, train all staff on how to talk about race and bias, establish an equity cohort, and implement a racism and bias curriculum, among other things, to support students of color and create a welcoming culture.

In terms of discipline, Nielsen said leaders in the district have “begun the process of thinking about what other mechanisms are there for modifying behaviors.”

“All too often in education, we see students that have gaps in English or math, and we teach them the skills they need,” Nielsen said. “And we see students who have gaps of behavior, or think about the emotional side of things, and we (use consequences) as a way to try to modify, as opposed to teach.”

Nielsen said it’s too early to give specific examples of what forms of consequences PSD is shying away from and what restorative practices it hopes to use instead, but they’re working on it.

District spokesperson Madeline Noblett said that PSD is working to educate staff through training courses on restorative practices; at a training earlier in the year, there were representatives from every secondary school. She said restorative practices will help increase social and emotional strengths and a “culture of caring” that can result in fewer interventions or punishment down the road.

PSD and equity: PSD provided an update on its equity work. Here’s what’s being done.

Ray Black, a professor at Colorado State University who researches the long-term effects of discipline disparities in K-12 education, said the disparities in PSD’s data, along with anecdotal evidence and larger conversations that are happening across the country, should be enough for action to happen now.

“Safety in schools is safe for who? The discipline data shows it’s not safe for all students,” Black said.

Dwayne Schmitz, PSD’s director of research, who prepared the data, was clear that while sharing this data was a step toward transparency in the district, it’s the beginning of a process and the data is not yet perfectly collected or analyzed.

“Discipline data is not like achievement data, It's not like attendance, and it's not like graduation rate, those things are very clean and crisp, and their definitions are clear,” Schmitz said. “So PSD continues its journey to clean up and make this data as reliable and robust as possible.”

But Black, who is also the father of a PSD fifth-grader and member of the School Justice PSD movement advocating for the removal of police from schools, said that even though the disparities in data should be obvious and lead to change, it’s oftentimes not enough.

“Seeing how bad the discipline is for a segment of the population is not necessarily convincing some folks because, you know, the prejudices and the other conceptions of what students of color (are) pervades,” Black said.

He added that while the board and the district have put out a number of statements in support of Black lives, transgender people and other marginalized groups, now is the time for action.

Some members of the School Justice PSD group believe that action should manifest in the decision to remove school resource officers, or SROs, from schools.

More: Front Range Community College plans to be 'close to full capacity on campus' next fall

SROs ‘don’t do discipline’ but their role is up for debate

One question that is not answered by the district’s discipline data is whether students of color are disproportionately disciplined by police stationed in schools.

Sgt. Laura Lunsford, who directs the SRO program for Fort Collins Police Services, said this is because SROs are not involved in school discipline — such as suspensions, detentions or expulsions — and only get involved when they’re called upon by staff or students.

“I think there's a perception that we're out looking for the problem,” Lunsford said. “The majority of the time, if we're being called to it, staff are calling us, parents are calling us, or kids are coming in to talk about issues where they've been victimized.”

PSD’s discipline data does contain a category titled “refer to law,” but administrators had different answers on what incidents the category includes and could not confirm if SROs were involved.

Noblett said the category is for situations where "there is an indication to district staff that an incident may have been a violation of the law." But Schmitz, who prepared the report, could not define it or clarify if the category involved SROs.

“The highlighting of discipline data within PSD leads to ongoing insights and system/practice checks,” Schmitz said when asked if the data was representative of student-SRO interactions, adding that he is “currently digging deeper.”

Last June, the PSD Board of Education voted to keep SROs in schools for the 2020-21 school year by a 6-1 vote. A number of board members said they needed additional data on SROs' roles in schools to support removing them.

Fort Collins Police Services does collect data on the calls its officers receive and the students they interact with, and submits it to the state annually. Similar to the district’s discipline data, the most recent SRO outcomes show racial disparities.

PSD Board President Christophe Febvre said he thought the board was “generally aware” of this data from FCPS but said members “are seeking support from staff to accumulate and present data from the various available sources.”

Noblett also said this data had been shared with the board, but some couldn't confirm if they’d seen it or even said they knew they hadn’t.

Board member Nate Donovan said he didn’t know that data existed, despite asking for it in the hope of “collecting information from as many sources as possible on the status of our school security and SRO programs and options for the future of those programs.”

The data showed that in the 2019-20 school year, SROs ticketed PSD's roughly 31,000 students 179 times; an analysis by race of the citations and arrests showed that 38% of these involved students of color. Data for the 2018-19 SRO outcomes had similar disparities, showing that 38.7% of the incidents involved students who were not white.

Data from FCPS on SRO interactions for the 2020-21 year is not available yet, but Lunsford shared numbers from the first semester and noted significant changes in how the department is responding to and tracking calls.

In the fall, FCPS began tracking the number and nature of calls officers responded to; out of 1,464 calls, just 12 students were ticketed.

The majority of calls were considered a “check-in,” “assist” or “no crime,” which Lunsford said could mean anything from an SRO being called from one school to another as a matter of routine to an investigation that found nothing wrong.

She said the change was made to track data more deeply in response to community calls for change and transparency. In the past, FCPS couldn’t say how many of the total calls officers responded to resulted in a ticket.

“We agreed that we've got to do a better job of tracking different data so that we can speak to it better, and so that we can also really take an honest look at it and see, is there a problem? Do we need to be addressing this differently?” she said.

The district and SROs are also taking steps to make sure that SRO objectives are more uniform throughout schools. In October 2020, the district put into place new standard operating policies that Lunsford said she hopes will create consistency in how SROs operate from site to site in the district.

Last spring, the board also approved the creation of the Community Advisory Council, or CAC, a group designed to help the district review the SRO program and “help determine if the program will continue.”

The CAC will present the board with data analysis and recommendations on whether to keep the SRO program on April 27. The board will likely vote on the matter in May.

More: Suspensions, handcuffs, jail – middle school discipline falls heavily on vulnerable kids

PSD is not alone in considering a change

Rena Trujillo, a leader in the Schools for Justice group and member of the district’s CAC, said the group has been actively discussing how to “move past statements of support and actually think about changing — structurally — the institutional and systemic racism that ... exists in the district.”

Trujillo noted that something that has kept the School Justice PSD campaign motivated throughout the year is that the conversations around discipline and law enforcement in schools have been happening at a larger level.

“We're not doing this work in silos,” Trujillo said. “This is actually, it's happening everywhere.”

Until just recently, Colorado was one of a number of states that had a bill in the legislature calling for schools to reevaluate how they discipline students.

Senate Bill 21-182 sought to address “disproportionate disciplinary practices and chronic absenteeism and supporting students at risk of dropping out of school.”

It would have required public and charter schools across the state to report discipline data, disaggregated by race, gender, status as a student with a disability and socioeconomic status, along with a number of other data points, to the state education department.

The bill would have limited the actions of SROs. For example, they would not have been allowed arrest students or issue a summons, ticket or notice that required a student to appear in court for certain offenses and conduct. They also would not have been allowed to handcuff elementary students.

"We have been disappointed by the divisive and inaccurate rhetoric around this (bill), we remain committed to lifting up the voices of students and families who have faced the consequences of harsh discipline tactics," sponsors Sen. Janet Buckner and Rep. Leslie Herod said in a statement.

Naomi Johnson, the one board member who voted to remove SROs last year, reiterated Trujillo’s thoughts that moving from support to action will require “a systemic change.”

“The very first thing that needs to happen is we need to accept that this is the system that we created, for better or worse, on purpose or by accident. It didn't happen by mistake. This is what we created,” Johnson said.

“And I think that right now, everyone in the district is looking at this and saying, ‘Wow, we do not like what we created.’”

PSD school discipline by the numbers

White students:

72.1% of population

60.2% of discipline

50.7% of detention

54.2% of law enforcement referrals

53.5% of in-school suspensions

52.9% of out-of-school suspensions

49.2% of expulsions

Latino students:

19.3% of population

31.5% of discipline

40.1% of detention

34.1% of law enforcement referrals

37.7% of in-school suspensions

38.4% of out-of-school suspensions

36.1% of expulsions

Students of two or more races:

3.8% of population

3.8% of discipline

2.8% of detention

4.5% of law enforcement referrals

3.3% of in-school suspensions

3.7% of out-of-school suspensions

9.8% of expulsions

Asian students:

2.8% of population

1% of discipline

0.7% of detention

0.6% of law enforcement referrals

0.6% of in-school suspensions

0.5% of out-of-school suspensions

3.3% of expulsions

Black students:

1.2% of population

2.3% of discipline

4.6% of detention

5% of law enforcement referrals

3.2% of in-school suspensions

2.6% of out-of-school suspensions

0% of expulsions

Native American students:

0.6% of population

1.1% of discipline

1.1% of detention

1.1% of law enforcement referrals

1.5% of in-school suspensions

1.6% of out-of-school suspensions

1.6% of expulsions

Pacific Islander students:

0.1% of population

0.1% of discipline

0% of detention

0.6% of law enforcement referrals

0.2% of in-school suspensions

0.3% of out-of-school suspensions

0% of expulsions

Molly Bohannon covers education for the Coloradoan. Follow her on Twitter @molboha or contact her at mbohannon@coloradoan.com. Support her work and that of other Coloradoan journalists by purchasing a digital subscription today.

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Poudre School District disciplines students of color at higher rate