As gun violence rips apart Charlotte lives, county builds first prevention blueprint

EDITOR’S NOTE: This reporting is part of ongoing Charlotte Observer coverage about gun violence, its impact on families and communities, and relevant public policy.

The numbers are bleak.

Homicides and gun-related assaults in Mecklenburg County nearly doubled from 2015 to 2020 — jumping from 64 to 126 and 2,279 to 4,405, respectively. About half that violence happened within five zip codes. The people targeted most often were young Black men.

Last year, county commissioners agreed to try something new here and in North Carolina, to treat the toll as a public health issue.

Dubbed The Way Forward, the plan seeks to cut the homicide and gun-related assault rates in Mecklenburg County 10% by 2028. The effort is organized by the Mecklenburg County Office of Violence Prevention, which has only two full-time and one part-time employees.

The numbers can be misleading.

The people really deciding The Way Forward’s priorities are community members. A long list of local groups are helping with implementation.

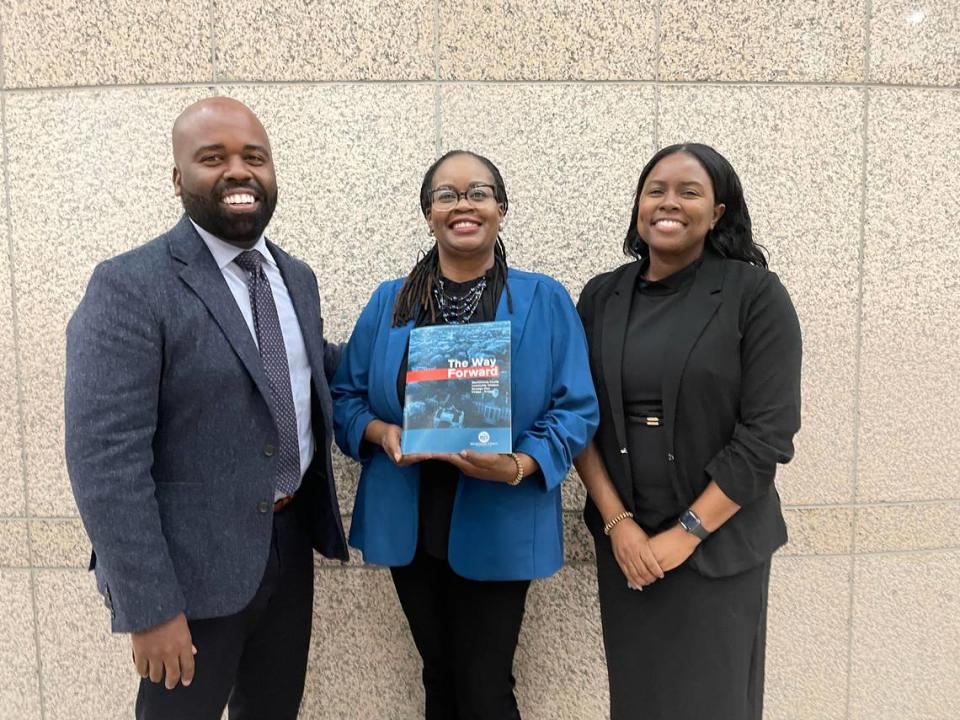

That’s a new approach, says Tracie Campbell, the violence prevention office director.

The Charlotte Observer recently spoke with Campbell about The Way Forward plan, what it means for Mecklenburg County and what it could mean for North Carolina. The conversation was edited for clarity and brevity.

CO: Why was the Office of Violence Prevention created three years ago?

TC: We had a lot of regular citizens that were asking local leaders, “What are you doing about all this violence that’s happening in Mecklenburg County?”

The response from Public Health was to develop this Office of Violence Prevention. At the time, our deputy health director, who is currently the health director, Dr. Raynard Washington, came from Philadelphia, where he was doing some work with their Office of Violence Prevention.

It was the response of public outcry to, “What are we going to do as a government entity?”

CO: Is The Way Forward unique with its community-centered response to violence?

TC: We didn’t want it to be a typical government type of plan, which is usually top-down. Government typically looks and says, “This is what the problem is, and this is how we’re going to address it. We’re going to develop a plan, and then we’ll show it to the people and implement this plan.”

Oftentimes when you do that, it is not addressing the needs of the people that you intend to serve.

We used a bottom-up approach where we went directly to communities to get their perception of violence and what they felt like we were doing well, what they felt like we could improve on are areas that were most salient to them. We engaged more than 400 residents in Mecklenburg County through online survey, focus groups and interviews, and really evaluated what they said, and came up with five areas of focus, which you see in the plan.

CO: You mentioned the solutions might look very different from what’s expected. What surprising things did you learn through that process?

TC: We had an opportunity to partner with the Sheriff’s Office and do some engagement with three pods within the Mecklenburg County Detention Facility. There were many people in those conversations who wanted to share their stories, share some of their pitfalls and talk about their successes and how they turned the leaf over from the life they used to live.

They want to share those experiences with young people. And one of the things that we heard from young folks is that they wanted to hear from people with lived experience.

So, one of the things we’ll look at: existing programs and policies and things that are happening in this space. There’s not a lot of opportunities for those two groups to get together. People with lived experience, if they have prior criminal justice involvement, they might not be able to mentor or volunteer with CMS, which is where we see most of our young people, in school.

We’ll create opportunities for those groups to share and hear and learn from one another. That’s a missed opportunity.

CO: The Way Forward is years long and not expected to be completed until 2028. What’s the work that’s being done right now and what’s next?

TC: Some of the things that we’ve already been doing is launching an awareness campaign about violence prevention. We have worked with the City of Charlotte and some other partners to expand our Alternatives to Violence Program. We’re working to support expansion of our hospital-based violence intervention programs.

Handle With Care is an initiative that will be launched through Pat’s Place (Child Advocacy Center), CMPD, CMS, the county and city. There’s some other partners in there. We’ll be looking at making sure that we are addressing the needs, the mental health and trauma of young people that have been exposed to a traumatic incident, whether it is violence, or it could have been a house fire.

100 Youth Advisory Council is about youth voices. A lot of times we don’t hear directly from youth about what’s happening, how they feel in terms of safety at school and in their neighborhoods. We’re looking to do a branch of middle school students, a branch of high school students and then a branch of 18- to 24-year-olds.

Peacekeepers Academy is an interactive learning series. It’s going to be specifically designed to help build capacity for our community-based organizations that are working in this space to reduce violence. A lot of these community-based organizations started out of personal tragedy. We know a lot of them have been doing great work and are still doing great work, but we want to help them build up the capacity to access funding.

CO: All of these ideas require a lot of collaboration. What it’s been like collaborating with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department, the Sheriff’s Office, the school system and building those connections to make all this happen?

TC: It’s violence prevention, but really it’s relationship building.

We’re helping people understand that we are here to support them, that our office’s role is not to reduce violence ourselves. If we could do it on our own, we wouldn’t need those partnerships. So, letting people know that we are not here to step on toes, that we are here to support and uplift whatever is going on currently in this space and to help them expand so that they can expand their reach.

CO: A lot of this violence happens in only a few zip codes, and it happens to a lot of young Black men. How does that affect intervention and programming?

TC: That goes back to intentionality.

A lot of communities are experiencing the highest rates of violence in Mecklenburg County, but those are also the same communities that are experiencing food deserts, and are experiencing the highest rates of COVID and there might be issues with access to affordable housing.

The disparities that some of these communities face are overwhelming and they’re disproportionate.That’s because there has been a lack of historical investment. When you tie all of these other issues on top of violence, these communities are really struggling.

Our data does say that the majority of people that are disproportionately impacted happen to be young Black males. How do we get to people before they get into a place where they’re struggling or they’re in trouble? So, we’re working very much upstream with younger people, which, again, is why we have decided that we needed to do this 100 Youth Advisory Council.

We spend a lot of money and a lot of time and a lot of resources having to help people who are already in a traumatic situation, or have already been exposed or had some type of life-threatening or life-changing incident as it relates to violence. Well, we could have poured into them much earlier, and perhaps prevented them from getting to the space that they’re currently in.

CO: This line in your North Carolina Medical Journal article that mentioned this is not something to replace law enforcement or “defund the police”. Why is that important?

TC: Not just in Mecklenburg County but across the country, we’re having to do a lot of education to say law enforcement are our partners in this work.

They can’t do it all, and for us to think that we’re putting the onus solely on law enforcement to do all this work, that just doesn’t make sense. Luckily we have law enforcement here in Mecklenburg County that supports the work that we’re doing, that supports this plan.

CO: Do you think a plan like this — because it’s fairly new, at least in North Carolina — is relevant to other cities across the state?

TC: I don’t think it’s unique to Mecklenburg County. It may have to be scaled down.

We think about Mecklenburg County, a large, urban area that has a lot of resources and a lot of things already in place. Some smaller communities don’t have as many resources or access to things as they need, but it is absolutely something that they can achieve.

You have to just, I think, leverage the partnerships that you have, make sure you know what is currently happening. And figure out ways you can support and expand the work that’s already happening, and look for those gaps in services where you can make inroads in other places.

It may not be that they’re doing what they think is specifically violence prevention work. But if they are doing things that are more upstream, and they are increasing the number of mentors that they have for youth, and more opportunities for youth, that will eventually move the needle.

Tracie Campbell’s North Carolina Medical Journal article on gun violence and public health, “Gun Violence is a Public Health Crisis in North Carolina: What Now?” can be found here.