The Publishing Industry Has a New Nightmare

Consolidation has long been the publishing industry’s buzziest, and probably spookiest, existential threat. Always a business in which a few huge companies could throw their weight around, it once had a “Big Six” that controlled the vast majority of the American book market. The Big Six became the Big Five when Penguin and Random House merged in 2013. The consolidation issue has not just come up in publishing, but also in distribution: Barnes & Noble tried to buy a huge book wholesaler in 1999 before giving up on the deal as it came under antitrust scrutiny. Any attempts to stop, say, Amazon from amassing enormous market power in a digital era of reading have been less successful.

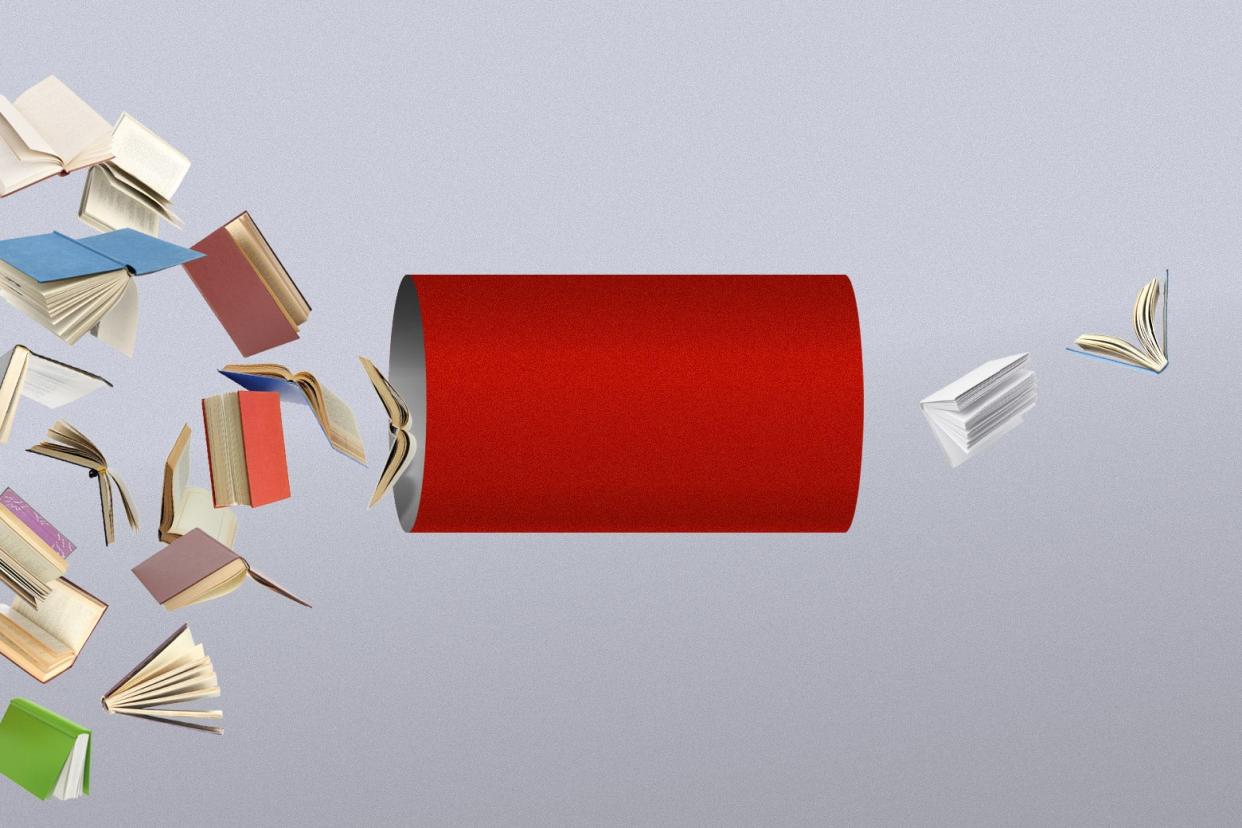

Simply put, there are not a lot of big publishing competitors out there, and there are not a lot of different ways for them or their authors to get those books in front of people who might like to buy them. That harms writers, who have fewer suitors to take chances on them and pay them, especially for ideas that are not proven commercial winners. And it harms readers, who have less variety to choose from as publishers tap predictable wells that they think will yield bestsellers. The problem is well understood and has generated a lot of consternation and press.

So it was a welcome counterpunch when, in November 2022, a federal judge blocked an attempt to shrink the Big Five once again, this time into a Big Four. Penguin Random House, itself a product of consolidation, tried to consolidate further by buying one of its chief remaining rivals, Simon & Schuster, the publisher of authors ranging from Stephen King to Bob Woodward to Hunter S. Thompson to Mary Higgins Clark. (Simon & Schuster, of course, is also a product of consolidation, having bought a bunch of publishers in its own day.) The judicial kibosh on that buyout cut against the grain and prompted much celebration from people who care about the health of books as a collective enterprise. People like, for example, King, who testified against the deal as the Justice Department sued to stop it: “The proposed merger was never about readers and writers; it was about preserving (and growing) PRH’s market share. In other words: $$$,” tweeted King.

So another Big Five publisher didn’t wind up gobbling up Simon & Schuster’s market share. But a different kind of institution just did: private equity firm KKR, which filled the vacuum left by Penguin Random House and bought Simon & Schuster for $1.62 billion this week. Book lovers avoided one of the remaining publishing giants falling into the hands of a different publishing giant, but they didn’t exactly get a homey acquisition by a company known for safeguarding books. A private equity firm taking over an enormous legacy publisher is different from another publisher doing it. But it remains to be seen if it will be any better, particularly if your interest in this story is as a writer or reader of books.

The best thing that can be said about KKR’s deal, to date, is that most of the other stakeholders in book publishing have not reacted with unmitigated horror. Book authors, agents, and sellers wanted to avoid an outcome in which Simon & Schuster ceased to exist as a bidder for books. A Simon & Schuster under the ownership of a private equity firm will still be a Simon & Schuster that exists to compete for authors in order to publish books. A version of the company owned by another big publisher would not, and the number of competitors for books would have shrunk by one. The Authors Guild, which advocates for authors, has taken a hopeful but maybe-a-little-skeptical tack. The guild “hopes that KKR as a private equity firm will defer to the editorial leadership at Simon & Schuster, recognizing that publishing is a unique business model that requires vision and creativity in ways that don’t always justify themselves on P&L sheets.” I also hope that, and you probably also hope that, but private equity firms are not known for ignoring profit-and-loss sheets in the name of preserving beloved traits of the businesses they take over.

Private equity is complicated in ways that its defenders insist media runts like me can’t possibly understand with nuance, but the basic business model is simple enough: Buy a company, generally with a lot of borrowed money, and try to get it humming before flipping it for a higher price. If the “get it humming” part succeeds, that is in theory best for everyone. The company does well, and employees keep their jobs and get raises, and authors get hefty advances for books that sell lots of copies, and it’s fantastic.

In fact, Simon & Schuster is already humming. It just reported a record sales year and seems to have been on the market in the first place mainly because its parent company, Paramount Global, saw it as “not core” and liked the chance to pay down some debt with the proceeds. A private equity firm’s specific designs for Simon & Schuster would be clearer if the book publisher were a disaster site, an iconic brand in need of better management so that it could return to its place as a literary pillar. But Simon & Schuster never lost that status in the first place, so KKR’s buyout lacks the patina of a rescue operation.

And the bad private equity stories are very bad. Private equity came for newspapers, and local news coverage in America is decimated. That sector is a particular cautionary tale because newspapers, not unlike books, are both businesses and something of a public utility. The world is dumber and poorer when newspapers are hollowed out—something that might have happened even if PE firms never arrived, to be clear—and it is similarly worse off when good books are less readily available. Private equity sometimes gets businesses working well, and other times it loads them up with so much debt that they drown. (This specific private equity firm is famous in part for one of the most disastrous leveraged buyouts ever.) KKR is borrowing $1 billion in its attempt to supercharge Simon & Schuster, where things already seem pretty good. What will happen, it’s reasonable to ask, if the publisher’s returns are not rapidly eye-watering? Could the ensuing situation be worse than if Simon & Schuster had fallen into the hands of another publisher that wanted to eliminate competition but at least had books in its DNA?

KKR would like everyone to focus on the more optimistic vision, the one where publishing workers are rewarded instead of laid off, where the company’s offerings get wider and better, and where Simon & Schuster can “become an even stronger partner to literary talent.” The firm says it is planning “a broad-based equity ownership program to provide all of the company’s more than 1,600 employees the opportunity to participate in the benefits of ownership after the transaction closes.” That sounds nice, much as KKR following the guidance of the Authors Guild and not running an ordinary private equity playbook with an iconic publisher of books sounds nice. It also cries out to a more skeptical ear that there is a catch somewhere, and a fair question would be: How many Simon & Schuster employees will no longer be Simon & Schuster employees by the time they could start owning stock?

Nick Fuller Googins publishes his first book, a climate utopian novel called The Great Transition, with Simon & Schuster subsidiary Atria Books this month. KKR’s nod to (extremely partial) employee ownership recalls an essay that Fuller Googins published at Literary Hub last fall in which he argued that an employee-owned and -operated Simon & Schuster represented the best possible outcome for the literary industry. I asked Fuller Googins what he made of his publisher’s new private equity parent as compared to the previous prospect of another publisher taking the reins. At least this wasn’t more consolidation, like the Penguin Random House deal for Simon & Schuster would’ve been if the feds hadn’t gotten it blocked.

But that premise, Fuller Googins pointed out, was shaky. “Ironically, that deal prevented some consolidation within the book industry, but private equity is probably responsible for more consolidation in the economy right now than any other force,” he said. “And they’re doing this from industry to industry.” He mentioned veterinary clinics, child care, and nursing homes. And while acquiring a Big Five publisher marks private equity’s splashiest foray yet into publishing, KKR’s deal is far from that industry’s first in publishing. Private equity investors have swung dozens of publishing deals already, with one firm snatching up as many as 10 publishing properties, according to Pitchbook.

“I do wonder if this is the beginning, if they’re now moving into a new industry,” Fuller Googins told me. “ ‘All right, let’s now start consolidating publishing.’ I don’t think it does prevent consolidation. It just kind of moves it over to a new sector.” Nobody seems to doubt that consolidation is a fire that could engulf the publishing industry if it hasn’t already. What if private equity is on the scene not with water, but kerosene?