Puerto Rico has some of the best COVID-19 vaccination rates in the US. Here's how the island did it

Jose Melendez Colón, 21, got vaccinated after his uncle died of COVID-19, gasping for breath on a ventilator.

Juan Felipe Santos, 43, survived a COVID-19 infection and decided he never wanted to get that sick again, so he got vaccinated.

Zelma Diaz Camacho, 32, delayed getting the shot. Then her childhood friend Angie died from COVID-19 complications. Diaz Camacho got vaccinated the next day.

“I was so mad at myself for not pushing us both to get vaccinated," Diaz Camacho said. "I let myself ignore science and what was right."

The three are among the 79% of eligible Puerto Ricans who have gotten at least one vaccine shot protecting them against the COVID-19 infection, giving this low-income, Democratic-leaning U.S. territory in the Caribbean one of the best vaccination rates in the country. Nationally, the rate for partial vaccination is about 70%.

As of Thursday, Puerto Rico hit 68.5% for full vaccination of eligible people, dramatically higher than the approximately 51% national rate. Island officials attribute their success to a combination of clear public health messaging and a near-absence of conspiracy theorists and the political divide that has marked the pandemic elsewhere within the United States.

And while Puerto Rican officials worry the delta variant is gaining strength, they are confident their high vaccination levels will protect the island's large elderly population.

"Every morning, I arise and say 'this is another opportunity to save another life,'" said Dr. Iris Cardona-Gerena, 60, chief medical officer for the Puerto Rico Department of Public Health. Cardona-Gerena, a pediatric infectious disease specialist, has spearheaded the island's vaccination efforts since the pandemic began.

'It hasn't always been smooth'

Battered by twin 2017 hurricanes Maria and Ira, beset by political scandals that saw its governor forced to resign in 2019 following a corruption scandal, and dragged down by debt, Puerto Rico's vaccination effort has outshone almost every other state. And the states it lags, which include Vermont, Massachusetts and Hawaii, are far wealthier.

Interviews with experts and residents across Puerto Rico reveal officials across the island didn't do anything special to achieve their nation-leading vaccination rates. Instead, they put together a textbook step-by-step plan with help from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – and then they followed it.

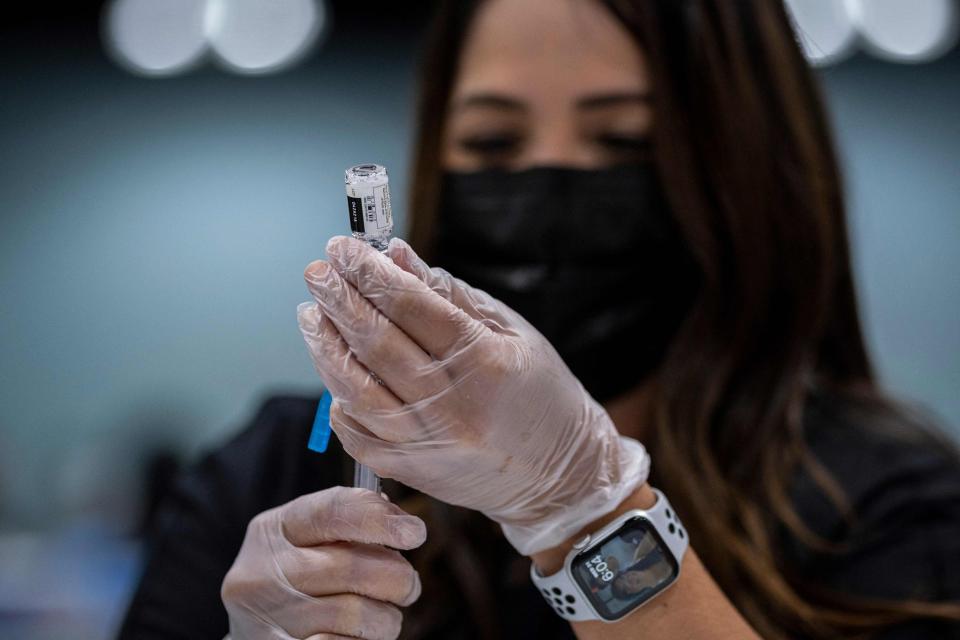

From publicity campaigns featuring doctors, nurses and politicians, to a highly organized National Guard distribution system, Puerto Rico's leaders offered clear, consistent messaging from the start, and are maintaining it as they try to reach the 20% of the population that hasn't been vaccinated.

Experts said official efforts were aided by Puerto Rico's history of good government-run health care, along with a vulnerable older population that remembers the plagues of polio and measles, which have been beaten back via vaccines.

Today, new government vaccination mandates for college students, concert-goers and anyone who wants to eat out or work in a restaurant are prodding younger people to get vaccinated. Further smoothing the way is mandatory sick leave and a near-complete absence of the vaccine opposition displayed in conservative-leaning states such as Florida and Texas, experts said.

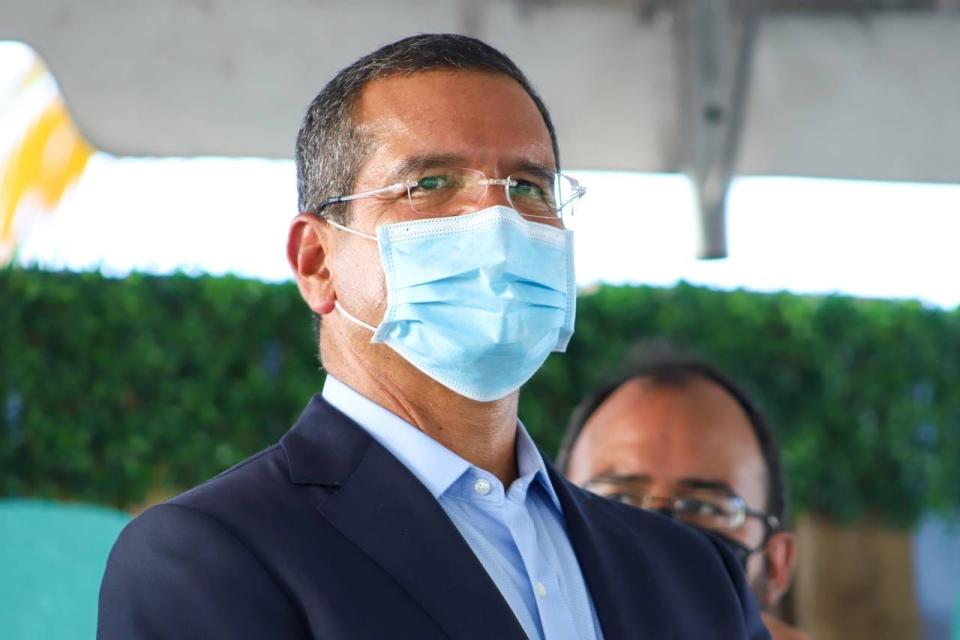

Gov. Pedro R. Pierluisi, 62, said his fellow Puerto Ricans' understanding and compassion has helped contain the pandemic, not just through vaccines, but with social distancing and masks. Unlike the reaction in many states, Puerto Ricans have overwhelmingly accepted his vaccine mandates.

"We went through Zika. We've been through Dengue fever. While we have never seen anything to this level before, our people, they are responsive and they are responsible in facing this pandemic," said Pierluisi, who took office in January. "This is a citizen's responsibility."

Pierluisi said the Biden administration has treated Puerto Rico like a state, rather than an unwanted colony, providing invaluable CDC guidance, along with funding that he is now using to pay $2,000 bonuses to newly hired hospital workers. While the delta variant is driving up hospitalizations, nine in 10 of them are among the unvaccinated, he said.

He said churches also played an important role by declaring that clergy would be vaccinated.

"We've been as creative as you can be, as flexible as you should be in facing this pandemic," Pierluisi said. "Every time we make decisions, we say we will be always willing to revisit them depending the stats."

Pierluisi said only a few Puerto Ricans have opposed his containment measures, which he characterized as "very sensible."

Instead of battles over wearing masks and skepticism over the vaccine's proven efficacy, a small group of protesters tried to shut down the island's main airport in July over fears that tourists and returning Puerto Ricans might flout mask mandates.

"It hasn't always been smooth. We've had some roadblocks, but we've tried to go through them using information," said José F. Rodríguez-Orengo, executive director of the Puerto Rico Public Health Trust. "We're very proud but there's still some work to be done."

Efforts based 'in science and data'

The island has long struggled to raise its economic and government institutions to the same level as U.S. states and many residents see strong public health as a key indicator of progress, said Carlos Suárez Carrasquillo, a Puerto Rico native and a University of Florida political science professor.

Suárez said many older residents remember when government-run health care was affordable and accessible, and are frustrated that a newer model of private clinics and hospitals, funded via government insurance, is less effective. Those older residents who remember the devastation of polio and measles before widespread vaccination campaigns eradicated them from the island were thus primed to be both receptive of the COVID-19 vaccine and government efforts to distribute it, he said.

"People historically expected more out of the state, and the idea of the individual pulling themselves up by the bootstraps is not as strong there as it is in the United States," he said. "The libertarian streaks that we have in the U.S. are not as strong in Puerto Rico."

There's also another, simple reason for some: The island's current health care system is widely considered poor because so many of its brightest young practitioners move to the mainland upon graduation. That means that even though Puerto Rico has four medical schools, many residents wait for hours for urgent care.

Jose A. Melendez, 53, a corporate attorney, said he got vaccinated against COVID-19 because the alternative was too much of a risk. "I didn’t want to face the possibility of getting sick and dealing with the emergency room," he said.

Suárez said Puerto Rico's government, media and medical establishments worked cooperatively to share the consistent message that COVID-19 was a serious threat and that vaccinations protect people.

Rodríguez-Orengo, of the Puerto Rico Public Health Trust, said there was a deliberate effort to ensure everyone was hearing the same thing, regardless of their political affiliation.

"When you have the commitment of the public health institutions in conjunction with other players who are eager to participate, we do much better than the states," he said. "We are based in science and in data."

Across the island, from doctor's offices to college campuses, medical experts and college students alike have been sitting down with those hesitant to get the vaccine, showing them the statistics of who has been getting sick, who is dying and how effective the vaccines have been.

Israel Melendez, 37, who helped found the nonprofit COVID-19 data tracker Task Force Ciudadano Puerto Rico, said double-checking the government's numbers and sharing that data publicly has helped reassure people.

“We still get calls from people saying the vaccine is a hoax or unhealthy or a plot from the government. But overall people are looking to live healthily and listen to science," he said. "What has also helped is in Puerto Rico, unlike in the states, there wasn’t a political agenda or discord regarding the vaccines. It was just understood that this was the right thing to do."

Melendez Colón, 21, a pre-med student junior at the University of Puerto Rico, has been spending his weekends distributing informational pamphlets to his fellow college students, hoping to reach a younger population that has been lagging in getting vaccinated. Melendez Colón saw his uncle struggling to breathe on a ventilator before dying from the infection.

"My background in medicine with my classes, mentors and internships help me tell people, 'OK, look at how many Puerto Ricans are vaccinated, here’s why and here’s where you can go,'" he said. "The success in Puerto Rico is a direct tie to the people’s hearts and wants; we want things to get better and we know what needs to be done. It’s not political and it’s not very hard, even for a lot of young people like me, we’re willing to do what is needed to end the pandemic."

Battling past medical mistreatment

While many white Americans during the pandemic have criticized the government's COVID-19 response over perceived threats to their liberty or individuality, leaders in many communities of color have battled vaccine distrust based on specific examples throughout the nation's history of medical professionals experimenting on the most vulnerable Americans. In Puerto Rico, this ugly history also exists, but experts said they have largely been able to sidestep these concerns because residents still consider health care important.

In 1956, U.S. doctors conducted in a poor neighborhood of Puerto Rico a yearlong trial of what was then a new drug: birth control pills. Few of the women participating in the trial knew it was a study as they consumed far higher doses of hormones than are used today, and the subsequent deaths of three women in the trial were never investigated.

The casually cruel way the poor women were treated remains fresh in the minds of some Puerto Ricans, including Diaz-Camacho, whose parents are historians. Diaz-Camacho said she worried the COIVD-19 vaccines were an extension of that treatment – ill-understood and experimental – until her best friend died.

“I was raised fully knowing and hurting from the trials women were put through and the fear of not knowing what I’m putting into my body. But when my friend Angie died, that fear was replaced with the fear of dying," she said. “Everyone I spoke to on the island told me to get vaccinated, the majority of Puerto Ricans are more scared of not getting their lives back and helping others than worried about a vaccine.”

While Diaz-Camacho got vaccinated, others who remember that past mistreatment worry Cardona-Gerena, the medical officer. She understands their hesitancy, but said she believes getting them accurate information will help change their minds.

Felipe Santos, an attorney, said he was impressed at how consistent the information has been. He said the government communicated effectively with private employers, setting up at-work vaccination clinics that reached many working people.

Many pharmaceutical companies have factories in Puerto Rico, and several experts said workers' familiarity with the drugmaking process in general likely helped reduce vaccine concerns. Felipe Santos said one pharmaceutical company he works with on the island has a 95% vaccination rate among its workers. He said the simple fact the government's COVID-19 statistics website works consistently helped persuade him of its competency.

"It's really easy to get vaccinated, it's everywhere right now. And the government has a lot of locations. You walk there without any appointment and they're there and ready," he said.

Cardona-Gerena said Puerto Rico finalized its vaccine distribution plan in October, well before receiving any shipments. Today, while she's still frustrated that people at first had to wait in line, she's also thankful the messaging had been so effective.

Simple steps like assessing how many patients clinics and mass vaccination sites could handle laid the groundwork for effective distribution, she said, along with freezer space donated by research universities. The National Guard then began delivering supplies daily, usually at the same time, allowing clinicians to use their time most efficiently, she said. Cardona-Gerena, who remains a practicing physician, appeared on newspaper front pages as she got her first shot on Dec. 16.

"We had a plan, we followed that plan, we followed the CDC playbook. And we had growing pains but were able to do it. And now we have to reach the 20% of the population that has not yet been vaccinated," she said. "I have hope, but I also am concerned that the delta variant and the effect that anti-vaccine people are having in the population remaining to be vaccinated. I am concerned about those messages, but I believe we are on the right track. I have hope that eventually we will win."

Rodríguez-Orengo, of the public health trust, said he and his colleagues have worked to spread a simple message: People who get vaccinated are heroes.

"We want people to know that we have accomplished something that countries that are more developed than us have not been able to do. If you're vaccinated, you're a hero. You're not thinking just of yourself, but of your family and your community. And that's what we are asking for," he said.

Diaz-Camacho, whose childhood friend died, said she wishes she had acted sooner.

“I would just urge people not to wait and sit on your own excuses. Do it before someone you love dies, or you do," she said. "I’m proud that Puerto Rico has had such high vaccination rates. It speaks to how willing our hearts are to help others.”

Contributing: Andrea Melendez, Ricardo Rolon, USA TODAY Network

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID-19 vaccination rates in US: Puerto Rico is a leader in pandemic