Puerto Rico statehood movement could be a sea change for voters

EDITOR'S NOTE: This page is part of a comprehensive guide to voting rights across the U.S. and in Puerto Rico.

Whether Puerto Rico should become a state, an issue that has historically affected voting rights, is back in the spotlight.

The nation’s oldest Latino civil rights group, the League of United Latin American Citizens, is calling on Congress to approve statehood for Puerto Rico. LULAC CEO Sindy Benavides said in a July 27 news release that “piecemeal” legislation is not enough.

“Statehood would provide the necessary stability for long-term planning, recovery, and sustainable development,” Benavides said in a news release. “Especially in the case of Puerto Ricans on the island who continue to fight for equality and basic civil rights as the Americans they are.”

Democratic Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Arizona introduced a bill on July 15 that, if passed, would allow Puerto Ricans to vote on three options: statehood, “sovereignty in free association” with the United States, or independence. If any option fails to garner more than 50% of votes, Puerto Ricans would vote in a runoff.

Benavides called for statehood at LULAC’s annual conference which took place in Puerto Rico from July 25 to July 30, where the group planned to hold internal elections. But members alleged in a lawsuit that statehood supporters held an unfair advantage, and LULAC President Domingo Garcia called it a “campaign to seize” the group. A Texas judge has since blocked the elections from taking place.

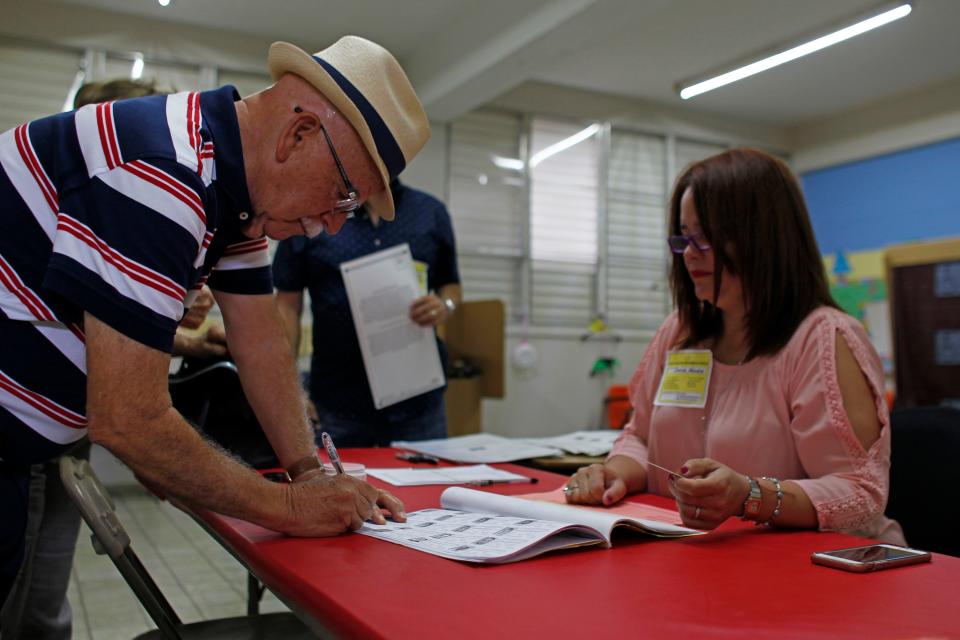

Puerto Rico experienced a nearly 10% increase in voter turnout from 2016 to 2020. If statehood advances, voters could weigh in on federal elections and gain representation in Congress.

Puerto Rico voting rights: a history of getting territorial

The issue of statehood has historically determined Puerto Rican voting rights.

When Spain ruled Puerto Rico, residents often lived under dictatorial rule, but sometimes gained political freedom. Puerto Ricans experienced brief periods of representation through the 19th century, at some points electing representatives to the Spanish parliament.

In the late 1800s, Puerto Rican political parties formed, some favoring an alliance with the United States and some favoring complete independence.

After the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States gained territories including the Philippines, Guam, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. After a brief military rule and temporary government, Commissioner Luis Muñoz Rivera demanded independence from Congress in 1916.

“Give us our independence,” Rivera said. “You will stand before humanity as a great creator of new nationalities and a great liberator of oppressed people.”

Rivera died the same year. In 1917, the Jones-Shafroth Act established a new Puerto Rican government, mirroring that of America and establishing citizenship for residents. In 1952, the United States allowed the territory its own constitution.

Puerto Rican citizens, however, cannot currently vote in federal elections and are not represented by voting members of Congress. Political parties can choose to include territories in the primary process, so Puerto Ricans help select each party’s nominee for president, and the territory conducts its own elections.

In 2012, Puerto Ricans voted on the territory’s political status with a two-part ballot measure. More than 50% of voters said they were unsatisfied with the status quo, and more than 60% of voters agreed upon statehood. Many left the question blank, however, so U.S. lawmakers questioned the results’ validity. Neither President Barack Obama nor Congress changed the territory’s official status.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Puerto Rico's statehood, federal voting rights gain uncertain momentum