How Punk Rock Helped Get Obama Elected and Other Miracles

For an excerpt from More Fun in the New World, go here.

John Doe, the singer, bassist, and songwriter in X for more than four decades, is as responsible as anyone for putting West Coast punk on the map.

In his brown yoked shirt and shotgun button detail, pointed-toe cowboy boots, and spit-greased dark hair with a silver streak pushed off his face (please let it be spit), he looks like a much more noir and much handsomer Buck Owens.

But let's not get romantic. By his account, he was kicked out of so many East Coast bands for being weird that he had to go west. He has dodged bottles, been spat upon, and ripped off enough to have finally become that someone who can talk about punk rock with the most authority and the least amount of bullshit.

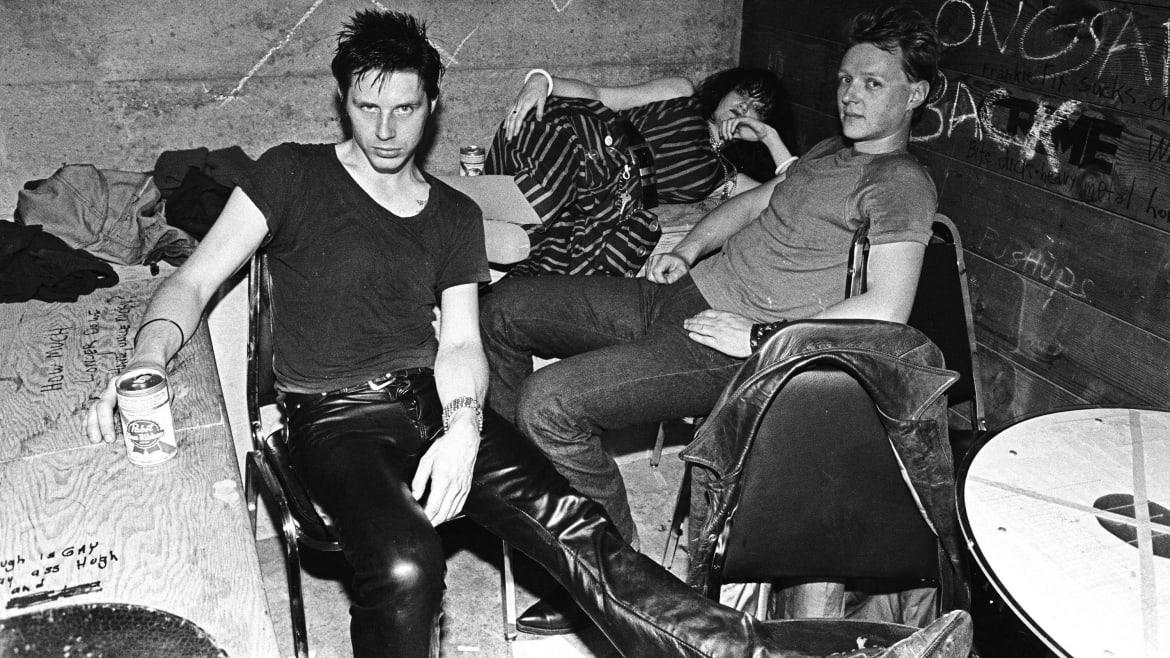

The juxtaposition of this lifelong punk apostle and the rear-to-front beige lobby of a midtown Manhattan hotel where we sit talking is disconcerting. These days Doe looks too debonaire for a van, and yet that's where I always imagine him. This hotel’s big, windowless room is for delicate people who dig taupe. Whereas the early X years took place in offensive spaces—cheap Los Angeles apartments (when L.A. still had them), sticky clubs without green rooms, and the Chevy delivery van that X customized to travel the United States.

Next to him, sporting a thick beard and an easy smile under a baseball cap, Tom DeSavia resembles an affable lumberjack. Together they are the co-editors of Under the Big Black Sun and, mostly recently, More Fun in the New World, a double-barreled history of L.A. punk as told by the people who created the scene and by those who simply felt its influence.

LA's Punk Rock Royalty Turns 40

Their More Fun in the New World book tour has them barnstorming across the country, doing the bookstore and public radio circuit, and New York is the latest stop.

Neither man acknowledges the song playing in the background: “Everything I Own” by Ken Booth. The ’70s hit predates X’s debut by two years and is pretty much what radio was still spinning when Doe, Exene Cervenka, DJ Bonebrake, and Billy Zoom started bringing the roots of American music to life with a little more speed and raw urgency than folks were accustomed to.

We get down to business. “Here’s the part where you said it in the book and now you get to say it again,” I joke.

Doe has a better plan. “We just shoot the shit and write about it.”

More Fun in the New World covers the next wave of punk—roughly 1982-1987. Jane Weidlin returns with a piece about quitting the Go Gos, her fights over publishing royalties (super not punk, but expected), and more drugs than anybody should do. Weidlin’s bandmate, Charlotte Caffey, describes her heroin addiction in a chapter that ends with the most heartfelt moment of surrender. And that’s just the Go Gos. There are echoes of that bleakness in other entries as well (Jack Grisham, Maria McKee).

But while the tone of the new book is darker than the first one, some of the bright spots are brighter, too. New writers join the party and bring something fresh, especially those writers who weren’t themselves punk rockers but were heavily influenced by their love of punk’s ethos. Actor Tim Robbins chronicles the earliest flash mobs. Tony Hawk was almost on the Circle Jerks’ Group Sex album cover when the band interrupted his skatepark session to be photographed in the bowl. Film director Alison Anders finally landed a star, a rock star, for her film—John Doe!

More Fun in the New World focuses on those who dropped the needle in the first book but also on the people who moved it forward from there. Moving forward often meant tapping the roots of American music and culture. Members of Los Lobos, Fishbone, Lone Justice, and the Blasters remind us that L.A.'s regional brand of punk was and is evolutionarily its own art movement.

“It’s funny what was defined as punk,” DeSavia says. And he’s right. Too many people still erroneously conflate punk with hardcore. X is punk, although their music is infused with “Little Richard or Jerry Lee Lewis, all the people who did that stuff,” Doe has said. “We reference Woody Guthrie, and we’re fans of that stuff, too.”

Already social media is full of criticism of the book’s contributors list, DeSavia says, all it of generated by that reductive idea of what a punk band sounds like: “The Go Gos weren’t punk. Los Lobos weren’t punk. The Blasters weren’t punk. And obviously they were. But I kind of understand where it’s coming from if you have this cartoonish impression of punk, which a lot of people have—not as an art movement.”

That kind of close-minded thinking came later. When the scene was happening, DeSavia recalls, the sense of anything goes was much more prevalent.

“The first time I saw X,” DeSavia remembers, “I was in the break-things phase of my youth. I had never seen anybody play like that. That was sort of the gateway drug. I had never seen anything like the Minutemen or the Plugz. It was like a sampler platter of punk rock. It really did all come from different places.”

DeSavia says that generally the reaction to the book has been surprisingly positive, and that readers embrace the “sampler platter” esthetic. “Seeing the response has been really great. Going through Twitter and Instagram, I saw something that said, ‘I never heard Blood on the Saddle and now I’m obsessed.’ And posting videos. I was like, Yes!”

“That’s the reward,” Doe adds. “There’s a lot of variety within a genre. But I think in L.A., it was the influence of Latino culture and the horizon being 150 miles away rather than 150 feet. And, you know, beer and black beauties. I mean, that’s where maybe the elements or the roots of rock and roll start showing up later.”

“The transition from ’76 to ’80, it was just us guys,” Doe says, describing the scene in the years covered by Under the Big Black Sun. “And then, ’81 to ’82, hardcore from the beach was really coming in and changing things. At the time, we were just pissed, like ‘You fucked up our scene.’ Really. It felt that way. Exene and I couldn’t go see like, the Circle Jerks or FEAR, because, even though we played with them a dozen times, we couldn’t go to their shows. These 17-year-old and 18-year-old kids would see us and say, ‘Oh, you guys are fuckin’ rock stars’ and give us all this grief. It was a pain in the ass. We wanted to see our friends’ bands. So, we just ended up not going to them.”

When DaCapo, the publisher, exercised their option for a second book after the success of Under the Big Black Sun, Doe’s reaction was, “Oh shit.” Because to him the ensuing years didn’t seem worth writing about. "Hardcore became dominant," he says. "A bunch of other people got signed to major labels and, therefore, lied to. They went on tour. You can’t keep a community together if the people are gone. People got on drugs big time. People got dead big time. You know, all this negative shit. And then four years, five years later, here come Motley Crue and Poison. And they win. That’s a fucking terrible book.”

Doe’s partner, Krissy Teegerstrom, came up with the question the book answers: “What about the seeds you sowed at the time?” What about the people you inspired, and not just musicians?

“We started thinking about it and we realized, ‘Oh, Alison Anders would be part of that result. Oh, we know Tony Hawk, right? Yeah, Tony Hawk is kinda there. Oh, and Tim Robbins is kinda that too. And they took all that ethos, that idea, and applied it to their art.” John Doe smiles. “So, we did good.”

They sure did. For some, that five years was the beginning. The energy had spread and artists kept pace. The clique of a hundred or so Hollywood punks had passed the baton without even knowing it.

Turns out the mosh pit those early punks found exceedingly vile was beneficial. In his essay, Shepard Fairey writes, “Contrary to the common belief that punk amplifies angry feelings and leads to aggressive and antisocial behavior, it actually diffused those feelings in me, or at least channeled them in more constructive ways.”

That sentiment gets echoed in the conversation between John Doe and members of Fishbone, when Norwood talks about the positive release in the mosh pit versus the negativity in the gang activity surrounding them on LA’s south side: “You’re friends with these guys before they were gangsters, and all I could think is, ‘Damn, all of that excess teenage testosterone that’s being used in gangster activities—this is a positive way to release it!’ That’s my first thought in the mosh pit!”

“When you saw Lobos,” Doe says. “They meant it. And they played loud. And they played a little faster. And the same thing with the Blasters. Yeah, they sounded like Sun Records—legit. Because they listened to all that stuff. And they learned their lessons through them. It was louder and it was faster and it was good songs. Same with Fishbone. They knew how to play, but that wasn’t the thing. The thing was, Let’s fuck some shit up. They could have stayed on the South Side and just fit into some more pleasant R&B world.”

Not that everyone in L.A. punk liked everything or everyone else. Louis Perez describes “a thousand middle fingers shooting up at the same time” the night Los Lobos opened for Public Image Limited. “Any other East Los Angeles Chicano band with the tiniest bit of dignity or any common sense would have retreated back to their safe bubble and resumed their routine of weekend gigs playing weddings and backyard pachangas,” he writes.

More Fun in the New World provides a broader perspective on the genuinely inclusive world of West Coast punk than anything we’ve seen before. “It feels good to have been part of something that developed into a network,” Doe says.

Sure, as hardcore headliner Henry Rollins points out, it was hardcore bands like Black Flag and D.O.A. that built the where-to-play (and get paid), where-to-crash roadmap of America that would be used by subsequent bands for at least a decade. “It was with the SST bands and D.O.A and all of us going out and doing the missionary work,” says Doe. “And then the Jane’s Addictions and the Pixies and the indie bands took advantage of that, because college radio came along. So now there was this whole network to take advantage of by the time of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Mudhoney. It was like, Boom! It was just waiting for them.”

Favorite chapters? Not surprisingly, Fairey’s is first. “We had an idea that this kind of ethos translated to somebody else,” says Doe. “It was as if I had mentally said, ‘This is what I want.’ And he gave us exactly what that was. It was eerie.”

Punk found a teenaged Fairey in Charleston, S.C. by way of hardcore compilations and skateboard videos. The coolest thing about Fairey’s story is that he didn’t just think about punk as a fan. He also thought about it as an artist and a graphic designer, as when he noticed that "several of my other favorite L.A. punk albums used red, white, and black as their color schemes, including X’s Los Angeles, FEAR’s The Record, and Youth Brigade’s Sound and Fury. Those were all albums I picked up fairly early on and, noticing the prevalence of the black-and-red color combo, started considering not only the visual power of those colors, but also the likely economic benefit of printing with only two spot colors.”

Years later, the “economic benefit” of printing with two spot colors blew the doors off the Obama campaign with Fairey’s "Hope" posters. That, and the unsanctioned street level promotion he learned from punk poster artists like Raymond Pettibone who papered walls and lamp posts across America, helped get Barack Obama elected.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.