'Pure elation': For East African novelists, this year's Nobel was no head-scratcher

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

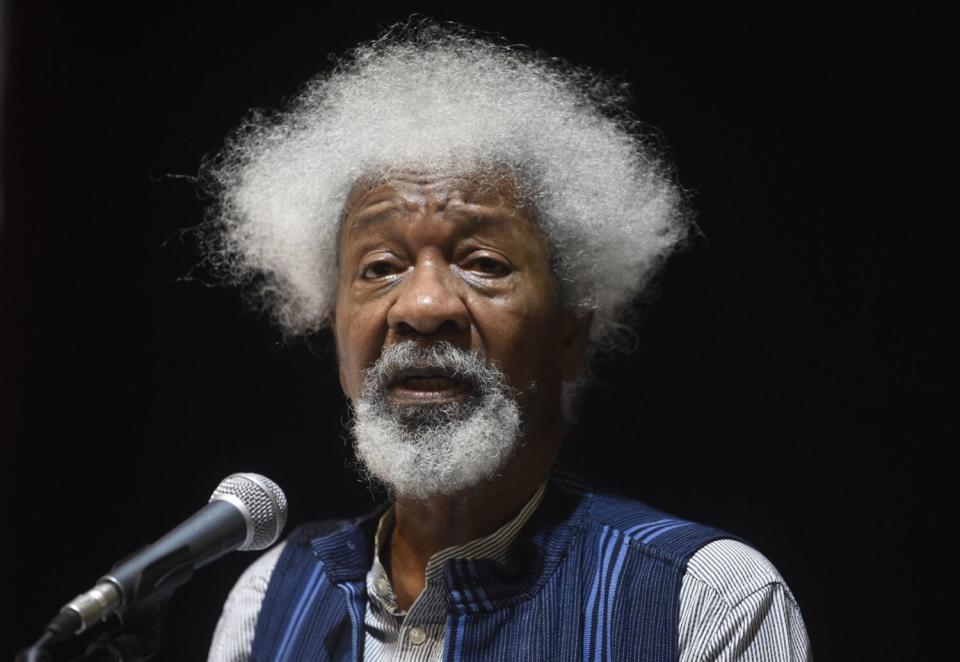

When Abdulrazak Gurnah was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature on Oct. 7 — the first Black African writer since Nigerian Wole Soyinka won it in 1986 — you could almost hear the head-scratching, at least across America: Who was Gurnah and where, exactly, was Zanzibar, the island of his birth? Of course, the Swedish Academy has been known for its unorthodox and sometimes obscure choices in the past, and even those who had followed Gurnah’s career for years woke up to a bit of a shock.

“My immediate reaction was surprise, as his name wasn’t ever mentioned as a contender,” remarked Caryl Phillips, the British-Caribbean author who has known Gurnah since the 1980s. “But, then again, I am surprised every year!” Phillips said, laughing.

Maaza Mengiste, the Ethiopian-born author of last year’s Booker Prize-shortlisted novel, “The Shadow King,” had multiple reactions, culminating in joy. “The news was a surprise, even for an award that seems to like to surprise us,” she explained. “And after my surprise, my next emotion was pure elation. He is a magnificent writer working diligently on telling stories that he wants to tell even if it seemed that not enough people were necessarily listening. His win is a triumph for every writer who wonders if their story matters when the spotlight is not on them.”

Indeed, Gurnah has spent his career plugging away steadily and without fanfare — though certainly not without influence or recognition among African authors of all generations. Gurnah’s 10 novels over the last four decades — including “Memory of Departure,” “Paradise,” “By the Sea,” “Desertion” and “Gravel Heart” — have charted a nuanced, layered cartography of colonialism in East Africa and the waves of revolution, exile and loss that followed in its wake. His novels often feature “ordinary people doing ordinary things in extraordinary times,” according to Mengiste — melancholy characters caught between memories of Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania, and a gray and lonely present in England.

Gurnah may not be as familiar to U.S. readers as other prominent “postcolonial” writers such as Michael Ondaatje, Salman Rushdie and Nuruddin Farah — or Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the Kenyan author many felt was in line for the award this year. But to fellow writers around the world, his body of work and steadfast persistence has had a profound impact.

The most visceral reactions were felt by those who have written from Gurnah’s region and under his influence. “Glee. Thrilled. Vindicated in my affection for both the writer and his works,” is how Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor described her initial response. The Kenyan author of “Dust” and “The Dragonfly Sea,” Owuor met Gurnah when he was on the jury that awarded her the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2003. She considers his Nobel an important acknowledgment of her own literary landscape.

“Gurnah’s work opened a window to the reality of the easy cosmopolitianisms of the East African worlds,” she said. “[He] wrote as if he were bypassing the imposition of the colonial imperative, as if the Swahili worlds were intact, were a continuum. This was always so refreshing. I adopted that attitude, of course.”

Owuor’s novels, like Gurnah’s, involve elaborate journeys and mixing cultures, exploring lesser-known stories of migrations across the Indian Ocean. “I love how he weaves in the African oceanic imaginaries, the long durée of African historical interrelationships with the world, and with itself,” Owuor added.

Mengiste concurred, saying she feels “indebted to Gurnah for his dedication to writing the stories of East Africa, of creating communities in his books that reflect the diversity of the continent.”

Gurnah has served as both model and mentor for Nadifa Mohamed, the British-Somali author of “The Fortune Men,” shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize. When Mohamed was working on her first novel, “Black Mamba Boy,” in 2007, she sought his advice. “I wanted someone who would understand what I was trying to do with my father's wild and woolly story set in East Africa and the Middle East in the ’30s and ’40s, and there was only one writer I could think of and that was Abdulrazak Gurnah,” she recalled. “He was the first person to read ‘Black Mamba Boy’ and I took his feedback to heart … and went home with a desire to write characters as subtle as his own.”

Mohamed aspired to emulate his “effortless, natural” style of interwoven storytelling, which breathed life into what might otherwise be seen as merely abstract or academic examinations of postcolonial displacement. “You can feel the warm air of the Indian Ocean running through his novels as well as the pitter-patter of English rain,” she said.

Not everyone was caught off-guard by the news of Gurnah’s prize. Brittle Paper, an online magazine of African literature, quickly posted a tsumani of praise from 103 African writers, including Soyinka. His contribution, titled “The Nobel Returns Home,” celebrates how “the Arts — and literature in particular — are well and thriving” in Africa, “a sturdy flag waved above depressing actualities by a young, confident generation.” He ends with a buoyant rallying cry: “May the tribe increase!”

In London, Wasafiri, the international magazine with which Gurnah has been closely involved for more than 30 years, gushed over the belated attention. As Susheila Nasta, the magazine’s founder, put it, “The recognition of Abdulrazak’s now undeniable contribution to contemporary international writing, and particularly to the world of African, Caribbean and Asian letters, has deeply moved me, as I have fought since the 1980s to bring such writing to mainstream prominence.” She added that “for Wasifiri readers the announcement … comes as no surprise.”

The first Nobel for an East African author was seen to recognize not only the region’s cultural power (manifested by Ngugi, Farah, Mengiste and many others) but the extraordinary range of the continent’s literature. “Gurnah’s win is a cause for celebration throughout Africa,” said Ben Okri, the Booker Prize-winning Nigerian author of “The Famished Road.” “He’s a writer of quiet, consistent steadiness, a writer of important themes. We are proud to have another literature Nobel to show the literary richness of our people.”

And yet, just as Gurnah’s novels portray characters in all their regional, cultural, familial specificity, the impact of his victory might be most deeply felt among individual writers who, like him, have worked for little more reward than the chance to be read and seen.

“It is an affirmation,” says Owuor, his fellow Swahili Coast author, “of the quiet ones who toil diligently and faithfully in the arena of their art, who do so out of love and who gently cheer on others. I am so, so happy that the world will get to know both this courtly man and his lyrical works and the worlds they inscribe.”

Even more, Owuor has found in Gurnah’s recognition a source of renewed inspiration for her own work. “It is always a boost to the spirit when an author one so admires, who is such a stylist, is also ‘discovered’ by the wider world and in such a dramatic way. I will toil away, toil away with a bigger smile pasted on my face.”

Tepper has written for the New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.