Is that purple? Glasses reveal the world of vivid hues for people with color blindness

Ray St. Clair first learned he saw things differently when he was about nine years old and walking down Congress Street in downtown Tucson with his mother.

"Look at the gray car," he said to her.

"Wait," his mom replied. "What color is it?"

The car was green.

That's how St. Clair, now 79, discovered he is color-blind.

It's never been a problem for him. His parents never made a big deal out of it. It never stopped him from doing anything. He joined the Army. He can discern traffic lights. He's not a bold dresser. And he worked as an audio recording engineer, where his ears, not eyes, were what mattered.

"I'm not quite sure," he said, "what I've missed."

He was about to find out.

On a recent Tuesday afternoon, St. Clair and three other color-blind people — all of them men, who are significantly more likely to be color-blind than women — arrived at the Arizona State Museum in Tucson.

They were there to try out glasses that promised to throw the exhibits around them and the world outside into hues they had never seen before.

There was John Turner, who had been plagued throughout his life with an inability to pick out matching clothes. Garrett Hoskinson, an archeology student who struggled to discern pieces of pottery embedded in the earth. And David Eerkes, a hobbyist woodcarver who relied on his wife to paint his finished creations.

Like most people with color blindness, all four can see some color, just not the full spectrum.

"Like that rug," St. Clair said, nodding toward a vibrant Navajo transitional blanket hanging nearby, its pattern bold and geometric. "I can see the colors in it. Distinguishing a couple of them is an issue."

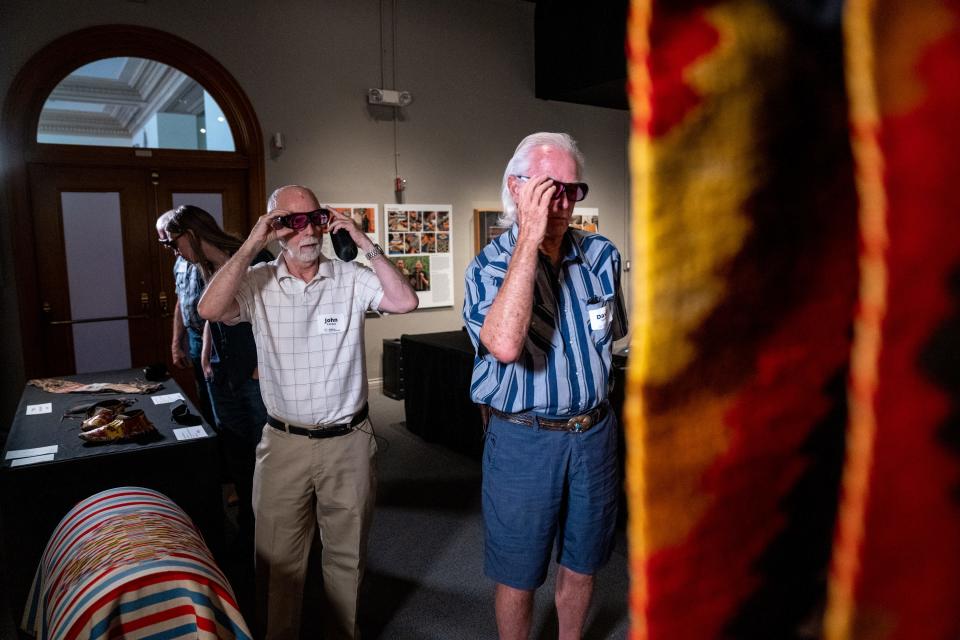

The four men looked a little uncertain as they stood before the blanket and other Native American art, each clutching a pair of dark glasses.

They were waiting for a signal from Lisa Falk, the museum's head of community engagement, who had chosen a bright purple shirt with vivid embroidery for the occasion.

"Okay," she said, "go ahead."

They put the glasses on and peered at the art in front of them. Hoskinson broke into a smile as he surveyed a blue beaded sheath.

Except for the occasional murmur, the room was silent until St. Clair spoke.

"Oh dear," he said. "That's way different."

He gestured toward the Navajo blanket.

"Well, the colors that looked pretty much the same to me before the glasses are now absolutely not the same."

He picked out two sets of stripes in the pattern, the first pair tan and beige, and the second red and orange.

Without the glasses, he said, each pair had looked the same to him in terms of brightness, intensity, saturation and color.

"Now they're way different."

'I do see some colors'

The glasses, which resemble ordinary sunglasses, were made by EnChroma.

The California company specializes in eyewear to address red-green color blindness, which is the most common form. This inherited type of color blindness is caused by deficiencies of the color receptors in the retina that take in red and green light. The EnChroma glasses filter light to increase contrast between red and green lightwaves, allowing the wearer to better distinguish between colors.

The EnChroma glasses are available for color-blind people to borrow at certain museums, national parks and other institutions across the world. In Arizona, they are available at the Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum, the i.d.e.a. Museum in Mesa, the Tempe Center for the Arts and now the Arizona State Museum. They are also available to buy, with prices for adult glasses starting at $229 and running up to $599.

Most color blindness is inherited, though it can also be caused by disease or injury. Three of the four men at the museum had relatives who were also color-blind. Only St. Clair, who has no brothers or sisters, said he wasn't aware of anyone in his family with the same condition. Eerkes had one young relative with monochromatism, meaning he only sees in shades of gray.

As he looked at the art in front of him, Turner periodically lifted the glasses up off his face and back again as he looked at the art in front of him. The change was immediate, he said, every color suddenly brighter, more vivid.

Turner said he has often encountered the misconception that color-blind people see no color at all. But while color blindness is relatively common, affecting one in 12 men and one in 200 women, monochromatism is rare, occurring in an estimated one in 30,000 people.

"I do see some colors and I love them," Turner said. The sunset, he added, is still beautiful.

"I imagine it is to everyone, because the colors we do see are amazing. It's just that we don't see the full spectrum."

As Turner inspected baskets, noting new shades that jumped out at him from the beading and weaving, St. Clair stood nearby, staring thoughtfully at a necklace.

Each large bead featured an intricate mosaic, bright turquoise on one side and a rich patchwork of the blue stone and coral shades of a spiny oyster shell on the other.

"I know the technique," St. Clair said, as he studied the distinctive jewelry. "And I know all of the zillions of colors in that thing. But I take these off" — he touched his glasses — "it's not nearly as distinctive nor as saturated."

St. Clair paused. Then he laughed.

"You know, it's much better to view with the glasses on."

As the four men moved through the museum, their focus was not just on art, but on anything colorful, including Falk's bright purple shirt, which she admitted she had worn on purpose.

"I'm not sure what purple is," Turner confessed. "Is your blouse purple?"

It was a common theme as the four men looked at things anew, often asking each other, or someone who wasn't color-blind, to confirm what color they were looking at. It was a habit formed from a lifetime of hopeful guesses.

"I'm usually right about what color something is," Hoskinson said. "But I'm never confident about it, I'm always second-guessing what it could be."

As the group moved outside, three trees proved a revelation.

When St. Clair walked past them on his way into the museum, they all looked about the same to him. Now he could see the leaves were different shades of green.

What about the stout barrel cactuses, popping up from a garden bed?

"All the greens are brighter to me. Just… deeper."

He moved his eyes up, to where the stars and stripes fluttered atop a tall white pole. "The flag is brighter too," he said. "The red and blue on the flag."

And up further.

"And the sky is different!"

The sky is different?

"It's bluer," St. Clair said, a hint of incredulity in his voice. "It's absolutely bluer."

'I don't need them'

St. Clair doesn't regret going through life seeing the world the way he has.

"It just never really mattered to me," he said. "It was never debilitating."

But given the option, he'll take the glasses. "Heck, yeah, why wouldn't I do that?" he said.

"But I don't need them," St. Clair added. "I could go around this museum and be pretty happy without these. I've done it a lot."

He can't recall a situation where he felt like he was missing out on a colorful scene, unable to appreciate the magnificence of a million hues.

"You know, a sunset, it's really pretty to me," St. Clair said. "And it's just differently pretty to the person without the color blindness looking at it. We both appreciate it."

He just doesn't know what they're seeing, and they don't know what he's seeing.

"So it's like we're equal."

Lane Sainty writes about people, places and events across Arizona. Reach her at lane.sainty@arizonarepublic.com.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Color-blind glasses help give wearers a chance to see more colors