Putin’s cyber shock troops turn their sights on Nato

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Vladimir Putin has often complained of the West waging a “proxy” war in Ukraine by supplying Kyiv with training and technology to fight back against Russian troops.

Yet even as Russia's leader convinces himself that he is the injured party, the Kremlin has been waging its own shadow fight against Europe and its allies.

Cyber attacks on Nato nations and their allies that originating in Russia have been ramping up in recent months, forcing the public and private sectors alike to beef up their defences.

“Europe was dragged into a high-intensity hybrid cyber-war at a turning point in the conflict,” says Pierre-Yves Jolivet, a senior cyber security executive at French defence giant Thales, who noted a significant increase in attacks at the end of last year.

Last summer there were 85 cyber conflict-related incidents in EU countries, according to Thales. Over the same time period its experts saw 86 cyber incidents take place in Ukraine itself.

Nicolas Quintin, a cyber security researcher with Thales, says: “Starting in May 2022, we've seen attacks in all of Europe.

“As soon as a country is, for instance, providing Ukraine with weapons or as soon as the country is blaming Russia’s actions, they react immediately in a very organised manner.

“The Russians’ goal was to send a message: ‘You can support Ukraine, you can blame Russia for the invasion, but it won't be without consequences’.”

The Baltic states on Nato’s northern flank have become the front line of Russia’s new digital offensive.

Margus Noormaa, director general of Estonia’s national cyber security agency, has said his country has “practically been in a cyber war” with Russia since its invasion of Ukraine. Attacks against Estonia’s digital infrastructure are “taking place almost every day or week”.

Märt Hiietamm, head of the agency’s analysis and prevention department, says attacks have become more sophisticated over time.

“This is from the people with the more professional stuff,” Hiietamm says, describing the split between Russia’s military hacking units and what he calls “the students for hire”. (These are young people, typically technically skilled civilians, who want to make easy money infiltrating Western companies for espionage purposes.)

Denmark’s Centre for Cyber Security (CFCS) raised the country’s cyber threat level from medium to high in mid-March, warning that “pro-Russian groups” have been stepping up cyber attacks “in Denmark and the West”.

“In the context of continued increased tensions between Russia and the West, pro-Russian cyber activists carry out numerous attacks against varying targets that they select from a broad selection of NATO members,” said CFCS in a statement.

Industry sources say there has been a marked increase in the number of stealthy Russian attempts to infiltrate computer networks for espionage purposes as well.

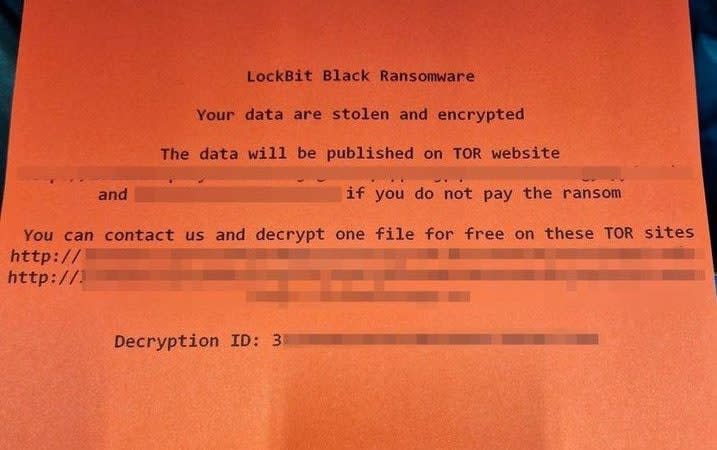

In Britain, major institutions have suffered several high-profile cyber attacks in recent months. Royal Mail’s international deliveries were notably brought to a halt by Lockbit, a Russia-linked ransomware gang.

Tony Adams, a senior researcher with cyber security company Secureworks, says: “We have seen indiscriminate pro-Russia hacktivism intended to cause a nuisance for organisations in Western countries that have openly supported Ukraine, but we don't consider those to be directed by the Russian state in any meaningful sense.

“Russian state-directed cyber operations have remained focused on two areas – disrupting critical services in Ukraine and spying on entities of interest to the state.”

However, dividing what is and isn’t a state-sponsored attack is notoriously difficult in Russia.

It was revealed last month that a civilian Russian cyber security consultancy, NTC Vulkan, had been training Russia’s elite cyber troops.

A cache of leaked documents revealed how the company had set up training ranges where members of Unit 74455 of the GRU spy agency, codenamed Sandworm in some Western circles, could practice hacking simulated power grids and even railways, with the aim of causing trains to crash or derail.

The incident demonstrates how porous the line between public, private and criminal is in Putin's Russia.

Moscow is stepping up cyber attacks as Putin gambles that these sort of digital offensives will not provoke the same kind of reaction as military force might.

Earlier this month the head of Britain’s National Cyber Force, James Babbage, told the Economist: “So far, our experience has tended to be that… cyberspace is more escalation tolerant than people tend to assume.”

Russia, it appears, has reached the same conclusion and is exploiting that increased tolerance for its own ends.

However, the spate of attacks has provoked senior Western military leaders to call for more digital arms to defend the West.

Nato secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg said in March that while conventional military force is needed, “they are not enough”.

“Strong societies and robust economies are our first line of defence. So we must secure our cyberspace, supply chains, and critical infrastructure,” said Stoltenberg.

Russia’s relative success at launching cyber attacks has attracted imitators.

Estonia’s Hiietamm says: “I would say it's mostly driven by the Russians but I think there is more awareness now – and some attacks have their origins from other states.”

Nonetheless, the Russian threat remains at the forefront of Western minds. Russia’s cyber troops are becoming bolder and less inhibited about targeting Nato members. Reinforcing the digital ramparts is now a top priority.