How Putin’s War Is Unleashing a Crisis Back Home in Russia

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Months after returning home to Russia from the frontline in Ukraine, he can’t escape the explosions, the violence and the terror. They echo through his head. Private Alexander Teploukhov has seen more carnage and brutality than any man should endure, some he witnessed firsthand, some he caused himself.

In episodes he calls “memory holes,” the 52-year-old is transported back to the Avdiivka combat zone in war-torn Donetsk, Eastern Ukraine. Every emotion rushes through him again as the scene unspools before him: his unit has to run; his partner is shot; they are digging; flames erupt; they run again. He can’t escape.

It’s “torture,” Teploukhov tells The Daily Beast.

Each episode lasts for two or three minutes, twice they struck him when he was on public transport. When he recovered, he found people staring at him. “When the nightmare ended, I had no clue where I really was or what I had done during the flashbacks,” he said.

Whatever you think of the soldiers in President Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine—some conscripted against their will, some brainwashed into believing it was their patriotic duty—the war does not end when they return home.

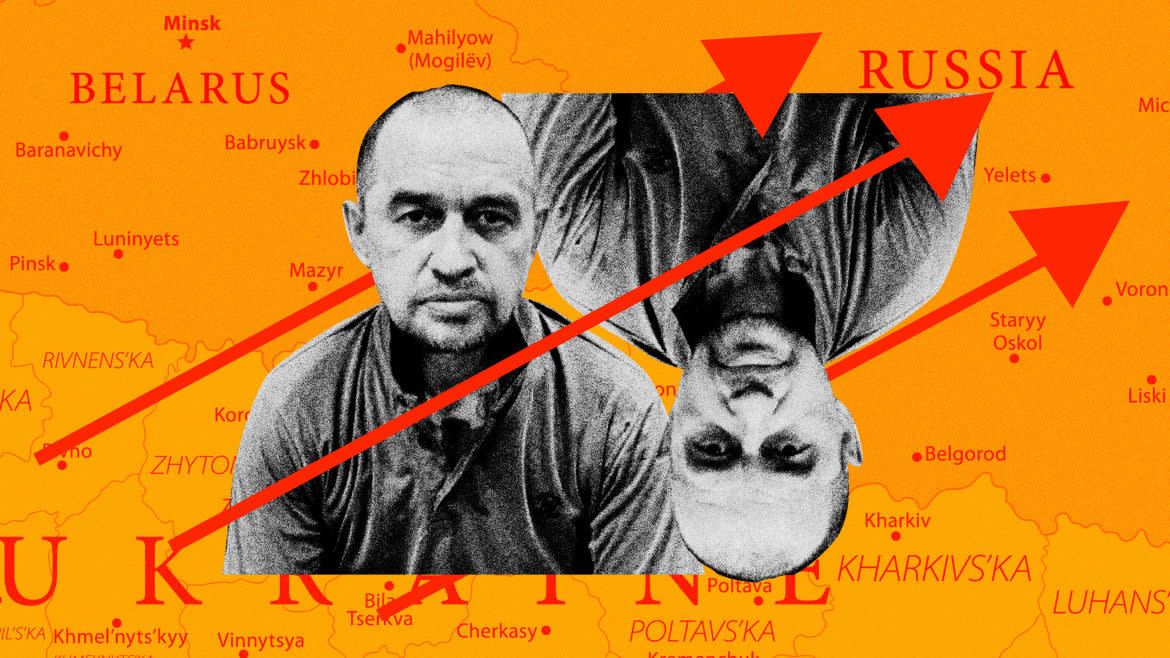

Alexander Teploukhov at home in Kurgan, Russia.

Teploukhov was wounded in February and went back home to his family in Kurgan, a city around 1,300 miles east of Moscow. “I limp but my limbs are more or less working. Psychologically, though, I am still not recovered: my young son witnesses my difficult relationship with his mother,” he said. “No sleeping pills help, my blood pressure goes up to 200, there is severe hypertension, crises happen almost every night. One psychologist told me she could not help me, I think she knew exactly how I felt.”

Teploukhov, who spent many years in prison for robbery and other crimes before the war, identifies with the news of other former soldiers of the Ukraine war, committing what seem to him “crazy crimes.” He feels a connection to these stories of violence being brought from the battlefield to life at home.

According to the Russian health ministry, up to 11 percent of Russian soldiers suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder but independent psychologists have a different opinion. “Absolutely every soldier who comes back from the front has some form of PTSD, that is inevitable but of course not every one of them takes a weapon to shoot people in the mall,” Olga Shelkova, a Moscow-based psychiatrist, told The Daily Beast. “We hear that some veterans seek help but the system of mental health for the military is so closed and so classified, that nobody really understands how the treatment works for soldiers with PTSD.”

One case was particularly striking to Teploukhov: On Aug. 7, Private Ildar Bulatov, 39, whom authorities had condemned as a “a deserter,” armed himself with hand grenades and took hostages at a gas station in the city of Ufa, 800 miles east of Moscow. The veteran was talked down after threatening to blow up the gas station if investigators didn’t shutdown the criminal case against him for deserting his military unit in Ukraine.

Since Putin started the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has investigated more than 500 criminal cases of people refusing to fight or deserting the front.

A photograph of Alexander Teploukhov, left, in Donetsk region of Ukraine.

Just like Teploukhov, who stole his wife’s fur coat to buy a ticket to join the war, Bulatov had volunteered to go to Ukraine.

Sergeant Rinat Kultumanov told a local media outlet that Bulatov “was not ready for a possible death,” so he deserted the front.

Teploukhov said he sympathized with Bulatov: “The guy felt it was unfair, how the authorities treated him plus he did not want to go to their doctor, so they pack him up and lock him up in some mental institution.”

Covered in prison tattoos, Teploukhov knew too well what life was like behind bars in Russia.

In June, just a few days before Putin’s soldier Yevgeny Prigozhin turned against him in a coup attempt, Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu claimed that over 150,000 Russians had signed the latest recruitment contracts.

Olga Romanova, director of the prisoner rights group Russia Behind Bars, says that “so far several thousand ex-prisoners—out of more than 50,000 Prigozhin said he recruited to Wagner’s “meat grinder” battles—have returned home.”

Pulled out of the brutal prison system and thrown straight into frontline battles where ex-convicts are treated as little more than cannon fodder by Russian generals or Wagner commanders, huge numbers have died on the battlefield. Those who survive are horrifically traumatized.

Several of them have already been accused of gruesome crimes on their return to civilian life. Ivan Rossomakhin, 28, was reportedly accused of murder during an eight-day break back home in the Kirov region after joining the Wagner Group from prison where he had been sentenced to 14 years for murder.

Locals said he had been stumbling around the village, with a pitchfork and ax, making wild threats, “I’ll kill everyone! I’ll cut up a whole family!” No one was able to stop him before he allegedly killed a woman.

Another convicted killer who was released to go fight in Ukraine has been arrested in connection with the murder of six civilians after he served his stint in the war. Igor Sofonov, 37, was reportedly released from prison to join Storm Z, which is the defense ministry’s state-backed version of the Wagner ex-prisoner brigades.

His six alleged victims were found in two burning buildings in the village of Derevyannoye.

Romanova and her prisoner rights group have been trying to provide support for Teploukhov, who says he has not received the pay owed to him for his service in Ukraine. “There is no doubt that 100 percent of all these soldiers, ex-prisoners, have bad forms of PTSD, many of them use drugs, drink a lot of alcohol—nobody provides any psychiatric help for them and there is a big chance that many of them will commit more crimes or die upon their return from overdose of drinking,” she said.

One of the founders of the Union of the Committees of Soldiers’ Mothers, Valentina Masliakova, says that most of the military contracts have not yet ended and that the PTSD problems will become “a major issue, a much bigger problem,” when thousands more traumatized soldiers return from the front. “For now, we have not heard of anybody, whose contracts actually expired, only Wagner soldiers are coming back, so far and wounded guys.”

Alexander Teploukhov, nickname "Teply," in Donetsk region of Ukraine.

Teploukhov was wounded in Donetsk in September but stayed on the front until February with torn muscles and a frost-bitten leg. “None of our guys could sleep at night, things we see before our eyes are happening as if they are real—I am looking for mines under my feet, every clap of thunder sounds like artillery fire,” he told The Daily Beast. “I cannot get any compensation for my service, for my wounds, I cannot buy my wife a new fur coat, so I just live on her account,” he said.

He admitted that he was struggling to control his anger and frustration, “I yell at my wife, and sometimes I get violent at home, which I am ashamed of later.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.