With quarter of landfall risk behind us, odds still high of a U.S. hurricane landfall

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The French painter and philosopher Paul Gauguin once asked, “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” As a humble scientist, I leave the middle question for humanities majors to ponder, but will point out that where hurricanes are likely to develop and then move is an under-discussed aspect of seasonal prediction. As Gauguin’s South Pacific home base of Tahiti is almost never impacted by tropical cyclones, maybe the guy was on to something.

Where hurricanes come from and go is important, as seasons with similar overall activity can have divergent human impacts. In 2004, nine Atlantic hurricanes caused six U.S. hurricane landfalls and $60 billion in damage. In 2010, twelve Atlantic hurricanes caused zero direct hits and pocket change losses.

Busier seasons, on average, do yield more U.S. landfall activity, but the relationship is weaker than you’d think. Even if you knew with metaphysical certitude how much Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) was going to occur in the Atlantic before the season started, you could only predict about one-third of the year-to-year differences in how much ACE happens over the continental United States. The rest of the variability stems from where storms develop, where they move, and, to be honest, a lot of dumb luck.

Last week, I discussed why WeatherTiger’s August hurricane season outlook has shifted more active since spring, with an uncertain forecast for net Atlantic activity about 50% higher than average. The primary culprit for this is across-the-board, Quiznos-level toastiness in Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs), with a pepper bar of especially picante oceanic warmth in the Gulf of Mexico. We’re not alone in noting this trend, with the consensus of seasonal forecasters rising from roughly 130 to 160 ACE between early June and today.

This week, I’ll dig into the thornier question of when and where that activity may pop up. Like grappling with Gauguin’s ontological quandaries or locating a Quiznos in 2023, that’s a tough task. But we do these things not because they are easy, but because they are toasty.

Where do they come from?

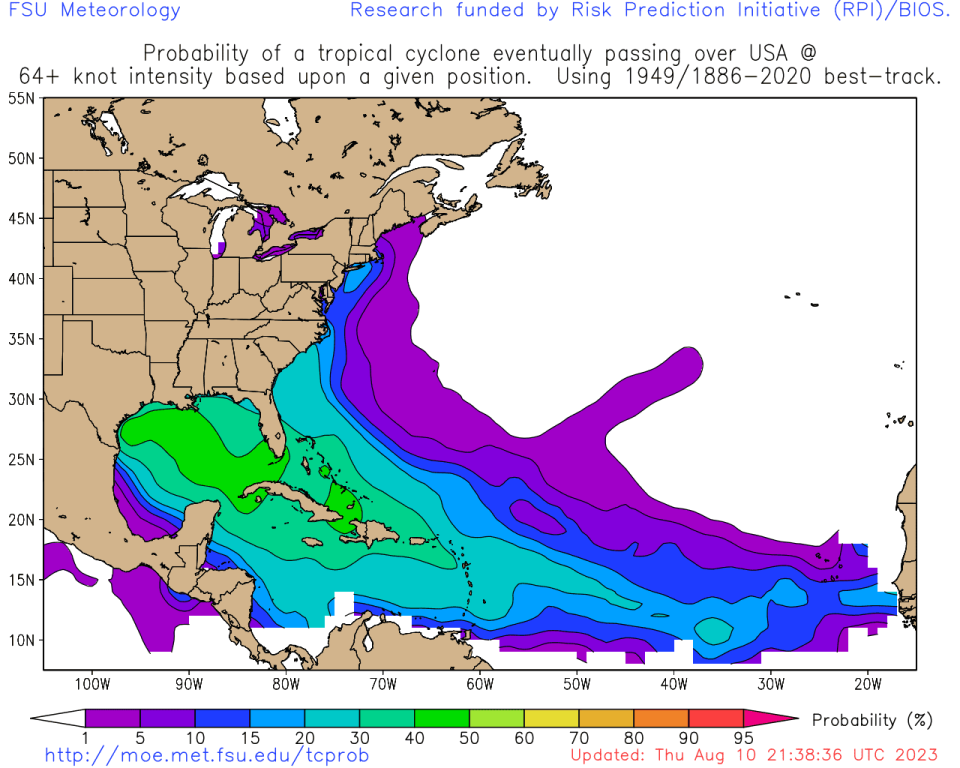

If seasonal hurricane forecasting is already a hard problem, predicting U.S. landfall risks is tougher than leather. A first step in that direction is to understand how U.S. impact risks vary with storm location; as shown, a random storm in the eastern Tropical Atlantic has about a 10% chance of reaching the U.S. as a hurricane, while one in the Gulf or Caribbean has a 30 to 40% chance of eventual U.S. hurricane landfall. Storms in central or eastern subtropical Atlantic are of no concern.

That historical analysis has the logical conclusion that a tropical system developing closer to the U.S. coastline has a better chance of making landfall. There simply is a much wider range of tracks that will cause a problem for a storm in the Gulf versus one near west Africa. However, storms usually develop in the eastern Atlantic only in August and September; early in the season and again in October, the environment in the Cape Verde region is unfavorable, and tropical development clusters in the higher risk regions closer to the U.S. coast. For this reason, June, July, and October account for around one-quarter of total ACE, but punch well above weight at over 40% of historical U.S. ACE.

This year, however, the shoulder season is a little less of a worry. Grimace’s Birthday and Shark Week have passed without incident, and a strengthening El Niño reduces odds of late season landfalls.

Per WeatherTiger’s analytics, the years that are the best historical matches to current El Niño conditions (and other key global dimensions of compatibility) are 1939, 1951, 1965, 1972, and 1997. In these five seasons, lower-level winds between August and October blew more strongly than normal out of the east, and more strongly out of the west at upper levels. This sharp change in the direction and strength of winds with height meant more wind shear (unfavorable for hurricane development) over the Caribbean, southern Gulf, and Lesser Antilles. As such, little tropical activity was noted there, and no U.S. hurricane landfalls occurred in October in any of those years. Interestingly, shear is already above normal in the Caribbean in 2023, and expected to stay that way into late August.

On the other hand, average upper- and lower-level winds in 1939, 1951, 1965, 1972, and 1997 were normal in the eastern Tropical Atlantic and southwestern subtropical Atlantic. With extreme ocean warmth in these areas and no historical signal for more inclement upper-level winds, areas east of 50°W or north of 20°N may be the preferred zones for storm formation this season. While these development regions are historically less risky for U.S. landfalls, the risk is, of course, not zero.

Where are they going?

The historical probability of U.S. hurricane landfall is not only dependent on where storms form, but the pattern of steering winds that move them about once they develop. With August and September accounting for two-thirds of Florida’s major hurricane landfalls and October likely hobbled to some extent by El Niño’s wind shear, it is the potential steering regime over the next six to eight weeks that is of the greatest interest in 2023.

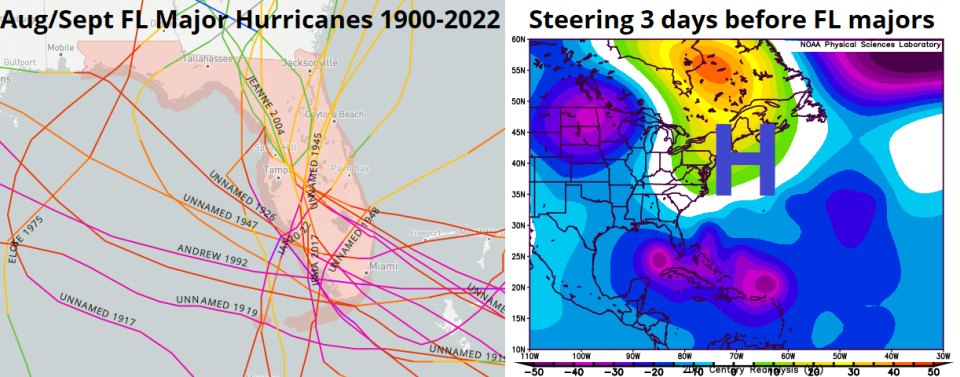

All of Florida’s 20 major hurricane landfalls in August and September since 1900 approached from the south or east and initially struck the Keys or southern half of the peninsula. Three days prior to these landfalls, there were strong, amplified high-pressure systems aloft over the western Atlantic and Eastern Seaboard. The clockwise windflow around these “blocking” ridges steered the storms west or northwest and prevented a turn into the open Atlantic. Furthermore, strong troughing over the U.S. Plains and central North Atlantic were also present to keep the ridge from sliding out of position.

The top analog years to 2023 do not show a close match to that inauspicious steering pattern. In August of 1939, 1951, 1965, 1972, and 1997, protective troughing was generally located over the U.S. East Coast, a pattern that so far has been repeated in 2023. However, in September, the analog steering pattern is more mixed, with indications of intermittent Southeastern or mid-South ridging. This signal is weaker and further southwest than the nightmare highs preceding catastrophic Florida landfalls, but it does hint that the door could be open for potential hurricane threats to the U.S. coast at intervals.

However, since development may focus on the eastern half of the Atlantic, many storms would also have to negotiate a potential trough in the central Atlantic plus wind shear obstacles before threatening the U.S. coast, which history shows is a tall order. Some analog and long-range modeling projects occasional high-latitude blocking in September, but overall the indications for the steering regime in the peak season are not particularly alarming.

What are we?

So, we’re looking at a 2023 hurricane season with more overall activity than normal, predominantly developing at an atypical spot. Steering wind risks are a push, and the final quarter of the season will likely be calmer than average. Unlike most other seasonal outlooks, WeatherTiger has developed a predictive algorithm that integrates the various components of landfall frequency into a specific projection of how many units of ACE will occur over the continental U.S. A normal year would have about 4 more units of U.S. ACE after mid-August.

However, our U.S. landfall risk model is coming in below this, at around 2.5 to 3 U.S. ACE units.

This is interesting, not only because it diverges from our above-average overall activity forecast, but because WeatherTiger’s U.S. landfall projection declined in July and early August.

Much of this decline simply reflects that about a quarter of U.S. landfall risks are now behind us, but it may also indicate that steering winds and preferred development locations aren’t particularly conducive to threats in 2023. Even so, our forecast translates to a 70% chance of at least one and a 40% chance of two or more U.S. hurricane landfalls this season. As a final note, our landfall model projected above normal landfall risks in 2022, which unfortunately was accurate. Here’s hoping for above-average forecast accuracy for below-normal landfalls in 2023.

In closing, the Tropics remain quiet, and are likely to stay that way for another week. Still, we know well that hurricane seasons can be nowhere to be found, then suddenly everywhere, like pickleball. While there is hope that the potentially active peak months ahead may not translate into destruction, it only takes one to moot that whole thesis so keep watching the skies.

Dr. Ryan Truchelut is chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger, a Tallahassee start-up providing forensic meteorology and expert witness consulting services, and agricultural and hurricane forecasting subscriptions. Get in touch at ryan@weathertiger.com, and visit weathertiger.com for an enhanced, real-time version of our seasonal outlook.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Hurricane season forecast: 70% chance of one U.S. landfall, 40% of two