Queen City Crime: A boat built in Cincinnati carrying Civil War prisoners exploded in 1865

The Cincinnati region has been connected to monumental crimes and criminals in years past. Here is a look at one of them.

The hook: A Cincinnati-built steamboat exploded in April 1865, killing some 2,000 people in what remains to this day the worst maritime disaster in the history of the United States.

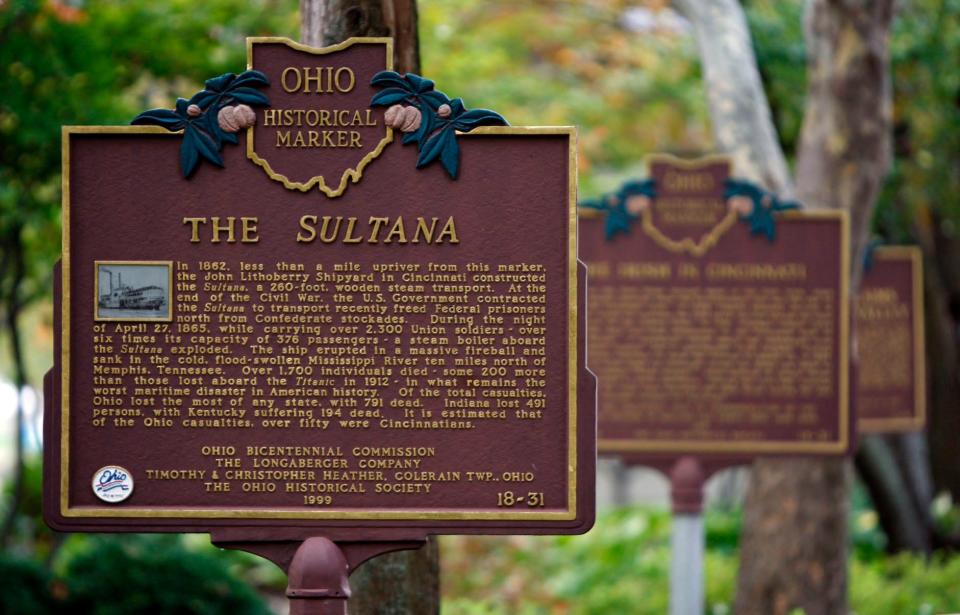

The SS Sultana was a 260-foot wooden-sided steam transport built in 1862 at the John Litherbury Shipyard on Front Street in Cincinnati. The factory is long gone, but a plaque about a mile from where it once stood commemorates the disaster and the role Cincinnati played in it.

“In the mid-19th century, Cincinnati was a major (riverboat) construction site,” Barbara Dawson, then a librarian at the Cincinnati Historical Society, told The Enquirer in 1999 when the plaque was proposed by history buff Chris Heather.

“Cincinnati’s role in the (Civil) War has always been downplayed,” Heather said. “The city had a number of factories that cast cannons, Cincinnati supplied many soldiers, including my own great-great-grandfather.”

While exploding steamboats weren’t unheard of at the time, the Sultana disaster immediately stood out: Not only was the boat filled well beyond legal capacity with Union prisoners of war eager to return home, but the decision to pack so many aboard one steamboat was made by military men promised financial kickbacks for doing so.

The steamboat: Sultana was a “mammoth looking craft for these times,” according to an 1862 Cleveland Daily Leader story announcing that the steamboat was “fitted out and ready for sea” and about to embark on its first trip.

A few months later, the newspaper noted the boat had hauled “the largest cargo ever taken from the Saginow (sic) valley” when it passed by with 750,000 feet of lumber.

Steamers were novel enough in the mid-19th century that local newspapers announced their arrivals and departures so people could line the river to watch. While the first steamboat was built by a Scotsman toward the end of the 1700s, the first successful U.S.-built steamboat came from Robert Fulton in 1807. As the decades passed, the boats got bigger, requiring more and larger boilers, which always posed an explosion risk.

“The biggest danger facing steamboats was boiler explosion,” according to “A History of Steamboats,” published by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “If boilers were not carefully watched and maintained, pressure could build up in the boiler and cause a spectacular and deadly explosion.”

The victims: The Sultana, initially intended to haul cotton along a regular route between St. Louis and New Orleans, was only approved to carry a regular crew of 85 and 376 passengers. And yet, when disaster struck, the boat had nearly 2,500 people aboard, plus dozens of horses, mules and hogs.

The reason for the overcrowding came down to money and opportunity. As the Civil War ended in April 1865, thousands of federal prisoners who were held at Confederate prisoner of war camps in Alabama and Georgia were paroled and brought to Vicksburg, and they hoped to head home. The U.S. government paid between $5 and $10 per prisoner to riverboat companies willing to take on the passengers. That government money trickled down to riverboat captains who were given a per-soldier bonus payment to jam as many prisoners aboard their boats as possible.

That’s how the Sultana came to be so overfilled. Its captain, James Cass Mason, stood to pocket at least $700 – or more than $13,000 in today’s money.

The blast: Capt. Mason not only erred when he agreed to take on far more passengers than the Sultana was allowed to carry, but he did so knowing that two of his four boilers had been giving him trouble. He had them repaired twice in recent voyages, and before the boat reached Vicksburg, where the prisoners of war were set to board, they gave out again. A local boilermaker found a bulge in the middle larboard boiler that was bad enough that he was amazed the thing had made the trip from its prior stop, New Orleans. Capt. Mason refused the boilermaker’s plea to dock a few days to give him time for a proper repair. Instead, the boilermaker slapped on a patch and watched as Mason refused to divert his stream of passengers to other steamers able and willing to take on some of the prisoners, too.

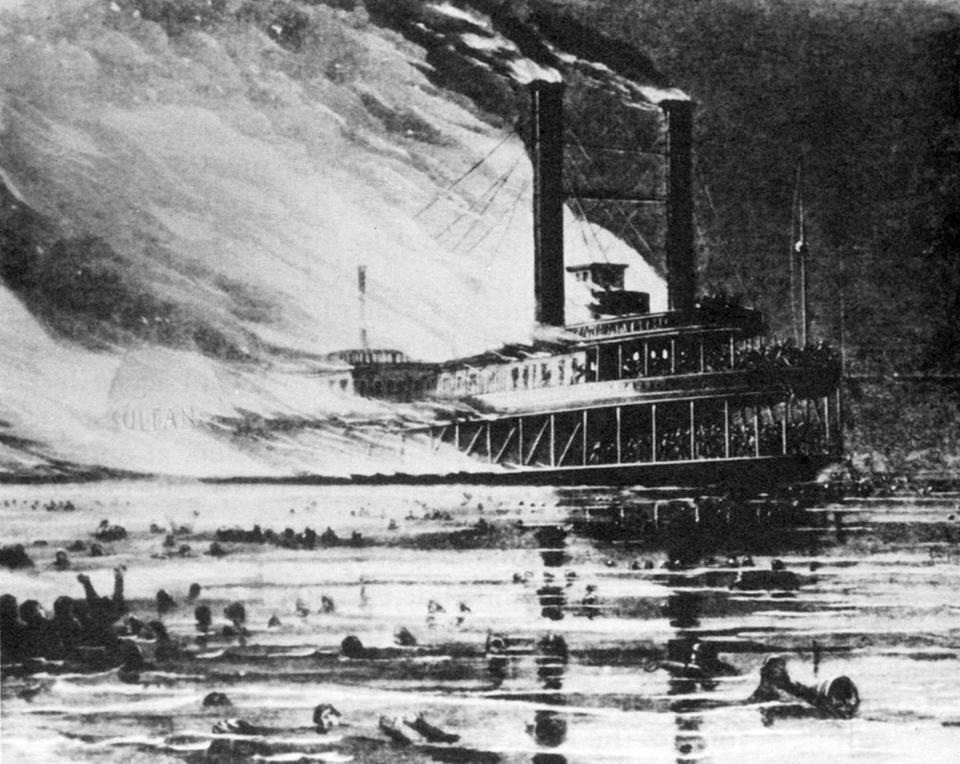

At 2 a.m. April 27, 1865, a few miles north of Memphis, Tennessee, as the thousands of passengers huddled awkwardly in hopes of getting some sleep, the patch affixed to the larboard boiler blew, causing two more boilers to explode simultaneously. Hundreds of people were instantly killed, while others awoke in the water disoriented. Most didn’t know how to swim and were in poor health from years as prisoners, making surviving the Mississippi River’s frigid water nearly impossible.

The alligator: This part of the story sounds made up, but it’s true: Aboard the Sultana was a pet alligator named Sal that the crew kept in a sturdy crate. A private named William Lugenbeal remembered that crate, sought it out, and killed Sal with a bayonet. (He apparently decided that tossing a live alligator into the river with drowning men would be ill advised.) Then he threw the crate into the water and rode it to safety. There’s a Sultana-devoted museum in Marion, Arkansas, outside Memphis, that still sells Sal the Alligator toys to this day.

The aftermath: Capt. Mason wasn’t injured in the initial explosion but apparently knew that he was at least in part to blame for the blast. Survivors reported seeing him tearing off pieces of wood from the wreckage and throwing them into the water for survivors to cling to. He was never seen leaving the wreck, apparently going down with his ship at 34 years old.

One of Mason’s superiors, Lt. Col. Reuben Hatch, was spared legal charges (or court-martialing, in military terms) largely thanks to his brother, Ozias Mather Hatch, who served as Abraham Lincoln’s Illinois Secretary of State. Lincoln had previously written letters of support when Reuben Hatch had been repeatedly accused of scheming to steal tons of money from the government. Although Lincoln had been assassinated two weeks prior to the Sultana’s explosion, Ozias Hatch still had considerable pull with the powers that be.

Another of Mason’s superiors – Capt. Frederick Speed – was the only one who couldn’t avoid a court martial. Speed was in charge of properly documenting which prisoners of war were boarding the Sultana but he decided to cut corners. Instead of carefully preregistering each prisoner, he opted to let them check in as they boarded, which led to hundreds more being allowed aboard than expected. Speed’s sloppiness initially got him convicted, but that was later overturned. No one else was ever tried for the disaster.

The tally of dead has never been confirmed – The Enquirer in 2011 put the count at around 1,800 – but most estimates put the count above 2,000. Only about 900 people survived, and that figure isn’t definite either because some 200 of the soldiers initially marked as survivors ended up dying from their injuries before ever making it home to their loved ones.

Enquirer journalist Amber Hunt is host of the podcast "Crimes of the Centuries" and co-founder of the Grab Bag Collab podcast network.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: The worst maritime disaster in US history involved a Cincinnati boat