Queen City Crime: Ohio's first assassinated president and his killer's link to a sex cult

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Cincinnati region has been connected to monumental crimes and criminals in years past. In this column, we’ll look at cases with local ties that were huge news when they happened.

The hook: If you’re ever grasping for some trivia to impress a friend, try this: The first Ohio-born president to be honored with a statue in Cincinnati was not only assassinated, but his death came at the hands of a deranged man with ties to an infamous sex cult, the name of which might be branded on plates and flatware in your kitchen.

If it sounds a bit complicated, that’s because it is. Here’s the overview:

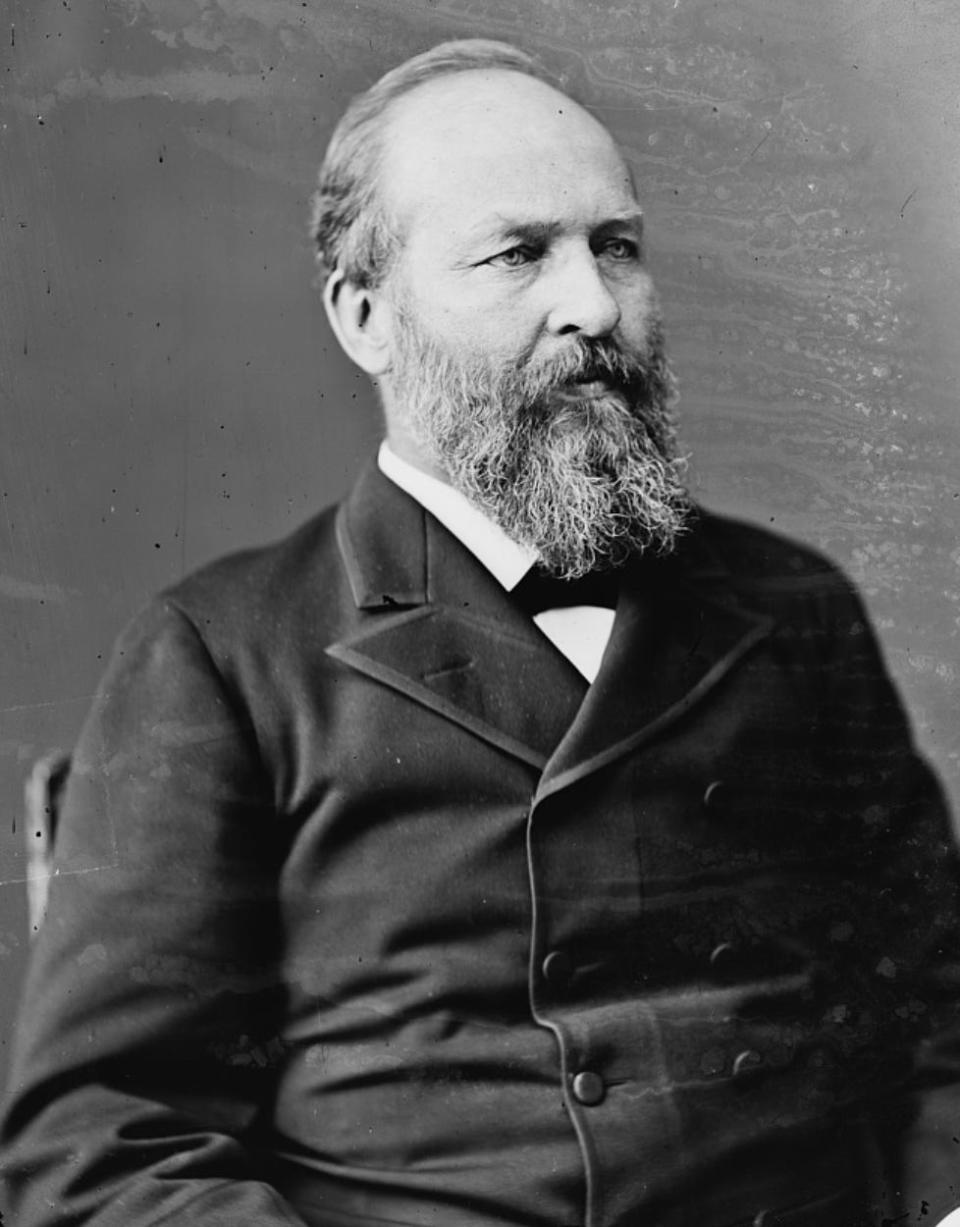

James A. Garfield was the final of four children born to Eliza and Abram – a farmer by trade and wrestler by hobby – on Nov. 19, 1831. The couple moved to Orange, Ohio, about 15 miles from Mentor, where Abram was mortally injured in a fire when James was only 18 months old.

“For a day or two, he suffered intensely,” reported an 1881 story in the Intelligencer-Journal newspaper. A “quack doctor” arrived to treat him by putting canthardidin, a secretion from male Spanish flies, also known as blister beetles. The poison was applied to patients’ throats in the 19th century, causing chemical burns that led to blistering around the throat. The thinking was that inducing a blister would draw out inflammation from the body, but Abram Garfield choked to death at age 33.

While Eliza was left to raise her four children in poverty, she worked hard to emphasize their educations, and James proved to be a stellar student. Like his dad, he was brawny, too, so briefly in his early years he ditched his academic pursuits to pursue a life of adventure working on the Erie Canal – a poor fit for a man who didn’t know how to swim. Garfield fell into the dingy water, contracted malaria, was sent home to recover and returned to his scholastic interests, which led him to teach at one of his alma maters, the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, which later became Hiram College.

He taught Latin and Greek and, at just 26, was appointed to be the school’s principal. An abolitionist, Garfield not only joined the Union Army once the Civil War began but he gave a rousing speech said to have prompted dozens of boys to enlist alongside him. He proved to be a shrewd and effective leader, with his success in the Battle of Middle Creek, Kentucky, later dubbed “the battle that made a presidency” because it resulted in the collapse of Confederate control in eastern Kentucky. His national profile rose, landing him in Congress, and, ultimately, the presidency. In 1881, Garfield succeeded President Rutherford B. Hayes, a Cincinnatian for whom Garfield supported in Republican rallies four years earlier.

Garfield had no way of knowing it, but his arrival at the White House would put him in the crosshairs of a partisan madman in a way that battle during the Civil War never did.

The assassin

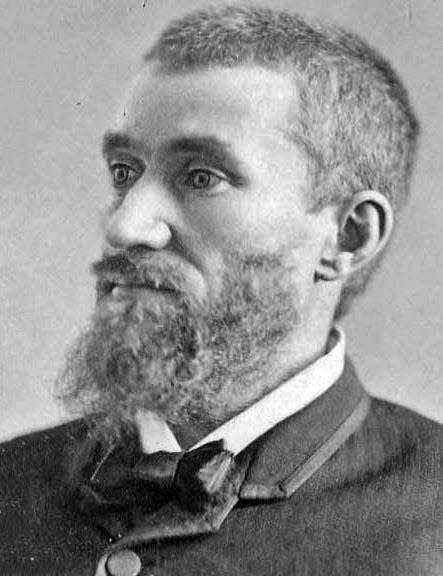

Charles Guiteau had been born in 1841 to unstable parents in Freeport, Illinois. His mother, Jane Guiteau, died when he was 7, leaving Guiteau to be raised by his father, who was a less than patient man. Guiteau sometimes spoke with a stutter, which his father, Luther, decided might be cured with whippings. (It didn’t work.) There’s less documentation on the efficacy of the beatings Luther administered to ensure his son’s piety.

As a young adult, Guiteau set off for the University of Michigan but didn’t last long. He left the school in 1860 and decided to join a religious commune called Oneida, named after the county in New York in which it was founded by a man named John Humphrey Noyes. Noyes eventually became convinced that while many Christians were awaiting the second coming of Christ, it had actually already happened, and that humanity was beyond needing to worry about sinning and had in fact progressed so far that the goal should be reaching perfection.

To become a self-sustaining utopia, Oneida made and sold things to tourists, which is the origin story behind the Oneida flatware company.

Its creator's view of perfection included “complex marriages,” aka polygamy, as well as incest. Noyes took on multiple wives, including adolescent blood relatives, some of whom bore his children. The commune was rather progressive on a couple of fronts, though: Women were encouraged to dress in the same manner as the men, with comfort and convenience prioritized over femininity and trendiness. Also, women were allowed to reject the advances of fellow commune members. This did not please Guiteau, who was disappointed that he was involuntarily celibate while a member of a commune preaching free love. Frustrated, Guiteau eventually left Oneida, bounced around New York for a bit and then moved to Illinois to become a bill collector. He stayed abreast of New York politics, however, and was a fan of a man named Roscoe Conkling, a former Oneida County district attorney who was elected to Congress at age 29.

A member of the liberal Republican party, Conkling belonged to the “Old Guard” faction known as the Stalwarts, which was at odds with the Half-Breeds. Both advocated for civil rights but diverged when it came to efforts to overhaul the patronage system. The Stalwarts were in favor of rewarding political supporters by assigning them consulships and other appointments. Garfield, also a Republican, was a member of the Half-Breeds, which worked to enact civil service reform. (The term Half-Breeds began as a racist insult coined by the Stalwarts as a way to say their opponents were, to tap today’s parlance, Republicans In Name Only.)

Garfield wasn’t keen on the spoils system, which ticked off two people: Conkling, who reluctantly had supported Garfield because Chester A. Arthur – a Conkling ally and fellow Stalwart – was his running mate; and Charles Guiteau, a political gadfly who’d given a few speeches supporting the ticket and considered himself a Stalwart. Both wanted their “spoils,” and both were rebuffed by Garfield. Conkling threw a fit and resigned his Senate seat. Guiteau felt something had to be done to unite the Republican Party – and he decided he knew just what to do.

The day

On July 2, 1881, Guiteau arose after a restless night in a Washington, D.C., hotel, ate a big breakfast and got dressed for his day’s big plans. He’d learned through newspaper reports that President Garfield planned to embark on a month-long vacation, for which he was set to board a train.

Garfield awoke in better spirits than usual – he found the presidency draining, especially with all the relentless office-seekers like Conkling and Guiteau – and also his wife, Lucretia, had been battling an illness for weeks. Lucretia and Garfield’s five children had started the family vacation a few days earlier; they didn’t know that when they boarded the train that day, Guiteau had been watching them, armed, but stopped short of shooting at Garfield that day to spare his frail wife the shock of watching her husband’s assassination.

This day, Garfield arrived at the train station with James Blaine, his secretary of state. The two entered the station by way of a ladies’ waiting room. Guiteau was already there. Once Guiteau spotted the president, he brandished his revolver and fired two bullets. One hit Garfield’s elbow, while the other lodged in his back. Guiteau quickly surrendered to a nearby officer, saying, “I did it, and I want to be arrested. I’m a Stalwart and (Chester) Arthur is now president.”

While newspapers quickly reported the shooting, the initial stories largely conveyed that Garfield would survive – which he did. For nearly three agonizing months.

The death

President Garfield’s condition vacillated wildly after his shooting. One day he’d be upright and eating, while the next he’d be given “nutrient enemas” meant to feed him through his anus because he couldn’t hold down food on his own. Just as was the case with Garfield’s father nearly 50 years prior, Garfield’s condition was worsened by the medical treatment he received. Contemporary notes from his attending physician, Dr. Willard Bliss, as well as family, friends and other witnesses, describe Bliss as repeatedly inserting his ungloved, unwashed fingers into the bullet wound in Garfield’s back in a vain attempt to locate the projectile and remove it. Ultimately, Garfield died Sept. 19, 1881, of starvation and sepsis. The Cincinnati Enquirer blared the news with an all-caps headline: “DEAD!” Among the subheads: “At 10:35 Last Night He Passed Peacefully Away, and Today Fifty Millions of People Are in Tears, After Nearly Eighty Days of Unparalleled Suffering, the Second Martyr President Finds Rest in the Grave.”

The aftermath

Guiteau seemed flummoxed that his slaying of the nation’s 20th president wasn’t applauded by fellow Stalwarts, including President Chester Arthur, who refused to pardon his predecessor’s assassin. Guiteau went on trial in November 1881. Part of his defense was his assertion that he hadn’t killed the president, but rather his doctors did.

Still, jurors found him guilty on Jan. 5, 1882, and sentenced him to hang 25 days later. On the gallows, Guiteau read a bizarre and rambling poem that included the lines, “I saved my party and my land, glory hallelujah, but they have murdered me for it, and that is the reason I am going to the Lordy, glory hallelujah.”

Four years after Garfield’s death, Cincinnati erected a statue in his honor – one of four nationwide that remain standing today. Commissioned in 1883, the bronze statue shows Garfield wearing a suit and overcoat with a stack of papers in his right hand as he gestures with his left. The sculpture was erected on a pedestal at Eighth and Race streets. Today it stands at Vine Street end of Piatt Park.

Enquirer journalist Amber Hunt is also host of the podcast "Crimes of the Centuries" on the Obsessed Network.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Ohio's first assassinated president and his killer's link to a sex cult