Queen City Crime: How serial killer Anna Hahn rocked Cincinnati, made Ohio history

The Cincinnati region has been connected to monumental crimes and criminals in years past. In this column, we’ll look at cases with local ties that were huge news when they happened.

When the first elderly man in Anna Marie Hahn’s orbit died, Cincinnati police didn’t suspect anything nefarious. Ernest Kohler was 62 years old and, Hahn told them, died May 6, 1933, of the esophageal cancer he’d been battling for years. When the coroner’s office received a few calls suggesting that Kohler had been poisoned, the doctor checked Kohler for poison and found no evidence, so his remains were sent to the crematorium.

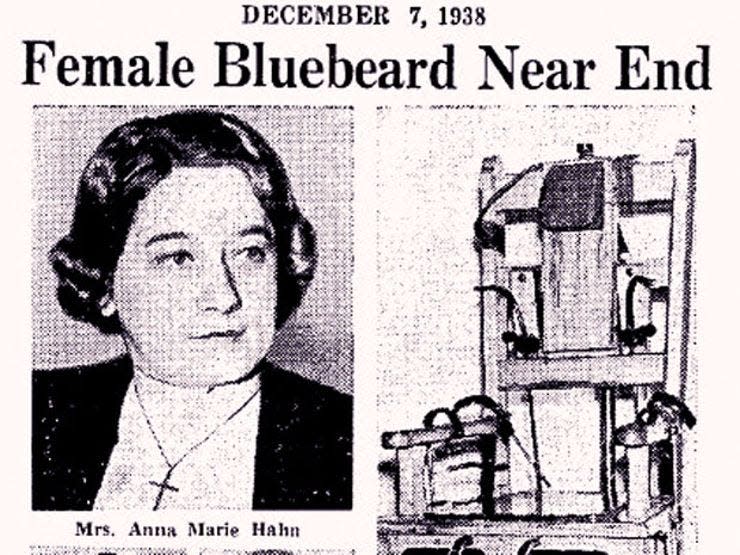

But then another of Hahn’s elderly male friends died. And another. Soon, all three of the then-existing Cincinnati newspapers were publishing thousands of words a day on what became one of the most historically significant criminal cases in the city’s history. Not only was Anna Hahn accused of multiple murders, making her a serial killer in today’s parlance, but she faced possible execution if convicted, which would make her the first woman in Ohio to die in the state’s electric chair.

About Anna

Anna had been born in Germany in 1906 to parents Katie and George Filser as the last of 12 children. (Five of her older siblings had died before Anna was born.) George, a furniture maker, provided a comfortable life for his family in a bucolic Bavarian town on the edge of the Alps.

Anna would later say that when she was a teenager, she fell in love with a physician from Vienna who she thought wanted to marry her. It turned out he was already married and broke off his relationship with Anna when she revealed she was pregnant.

Anna gave birth to a boy she named Oskar, whom she left in her parents’ care so she could travel to America and put down roots. When she returned in 1930 for her 5-year-old son, she was engaged to Philip Hahn, who adopted Oskar as his own. The new family tried to open a few businesses, but the Great Depression ensured those endeavors failed. Philip, by trade a telegrapher, couldn’t afford the lavish lifestyle Anna envisioned, so she began a new enterprise of her own.

The men

Kohler – the Hahns’ landlord – had taken a liking to Anna straight away. So did other men she befriended, who all had similar backgrounds: They were on the elderly aside – at least 30 years older than Anna’s late 20s – and they typically spoke German. They loved talking with Anna about the things they missed overseas while she would cook for them traditional German dishes.

To outsiders, these friendships seemed sweet, so when Kohler died and left Anna his house, a car, $1,000 in savings and fancy furniture – worth about $300,000 total in today’s money – they chalked it up to good karma.

But Kohler wasn’t the only man in Anna’s life. Next came George Heis, a 63-year-old coal dealer who wanted Anna to marry him, and who began lending her money when she said that she planned to divorce Philip. Heis quickly ran out of personal funds to loan so he started tapping the business account at his employer, Consolidated Coal Co. Once the tab reached $2,000, a company accountant asked Heis for an explanation.

Heis came clean: He’d been skimming for his girlfriend, who he swore was good for it. The accountant wasn’t so sure. He reached out to Anna for repayment.

This prompted Anna to establish a sort of Ponzi scheme of sorts, meeting new men from whom she’d borrow money, with which she’d pay back Heis, and then when those new men started asking for their loans back, one of two things would happen: Either Anna would find a new mark, or one of her existing marks would turn up dead.

More deaths

Albert Palmer died March 26, 1937, of what authorities at first believed was a heart attack. Within months, a gardener named Jacob Wagner joined him. Wagner’s death was the first to draw public scrutiny, in part because Anna had claimed to be his niece to other people living in his apartment building, yet Wagner bragged to friends that the two were readying to marry.

Wagner also had started complaining to friends that he often got sick after eating food Anna made him. One meal landed him in the hospital retching in pain, and Wagner died within days.

“I had known Mr. Wagner for a long time. He had never been sick before,” Fritz Grafemeyer told the now-defunct Cincinnati Post for an Aug. 14, 1937, story. “I thought there was something funny when he went so quick. People in the neighborhood were talking about a woman who claimed to be his niece, visiting him. She told me she was not his niece.”

Grafemeyer’s outcry led the prosecutor’s office to exhume Wagner’s body for posthumous poison testing. Suspicions grew more after police found the body of George Gsellman, a 67-year-old German-speaking Hungarian immigrant who bragged to his friends he’d found himself a German schoolteacher to marry. Gsellman – whom The Enquirer described in a story as a “pathetic, lonely old man who lived in almost abject poverty” – was discovered dead with a half-eaten meal still on the stove. In the pot were 18 grains of arsenic, which author Tori Tefler wrote “was far more than was necessary to kill a man.”

The final death

With authorities closing in on her, Anna left Cincinnati, taking son Oskar and yet another older German man with her. This time, her “friend” was 67-year-old George Obendoerfer, a retired cobbler. As the trio took a train to Colorado, Obendoerfer fell ill. By the time he reached the Oxford Hotel in Denver, he was writhing in agony, covered in his own vomit and feces. Hotel staff insisted that the woman and child accompanying him get him to a hospital.

They didn’t. Instead, Anna moved Obendoerfer to another hotel called the Midland, where staff members reported seeing her bring the deathly ill man watermelon that appeared seasoned with salt granules. Within days, Obendoerfer died.

The whole scene seemed peculiar, but what caught law enforcement’s attention was a report that Anna had stolen a couple of diamond rings from one of the hotels. Colorado police followed Anna to Cincinnati, where she was arrested for grand larceny. Local police who’d been investigating her on suspicion of murder were intrigued to learn her companion on her trip west had suddenly died.

The trial

Newspapers soon gave Anna sensational nicknames, including “the Blonde Borgia” and “Cincinnati’s Angel of Death.” Her trial began in October 1937. While she was charged only with Jacob Wagner’s death, prosecutors got the judge to agree to hear evidence about the similar deaths of several of the other men introduced into evidence.

Anna's husband Philip at first stood by her side, saying he couldn't believe the allegations. As the trial began to unfold, however, he stopped attending. He never officially divorced his wife, but he quickly disappeared from her and Oskar's lives, as well as the public view.

Prosecutors paraded 113 witnesses to build up their case in a trial that lasted nearly a month. The most damning testimony came courtesy of George Heis, whom prosecutors called the “living witness.” The Enquirer reported that he was “wheeled into the courtroom to point a quavering finger at the stony-faced blonde and say, ‘You did this to me.’”

In contrast, the defense called just three witnesses: Anna, her son Oskar (now aged 12) and a Chicago chemist whose testimony was virtually ignored by reporters. Oskar swore under oath that his mother hadn't hurt a soul and even claimed that poison found in their home and in her purse had come from one of his "chemistry sets."

A guilty verdict seemed inevitable to court onlookers. What wasn’t certain was how they’d sentence Anna. They could recommend life in prison or the death penalty. They went for the electric chair.

Anna held out hope that the judge overseeing the case would override the jury’s recommendation, but he didn’t. On Dec. 7, 1938, Anna spent hours crying with Oskar before jail officials nearly carried her to the death chambers. She pleaded with the witnesses to intervene, saying, “Please don’t. Think of my boy.”

After Anna went down in history as the first woman ever killed by the electric chair in Ohio, her lawyer stepped forward with a letter she’d written confessing to the crimes.

Try our Cincinnati history quiz

Enquirer historian Jeff Suess contributed to this story. Amber Hunt is host of the podcast Crimes of the Centuries and co-founder of theGrab Bag Collabpodcast network.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Killer Anna Hahn was the first Ohio woman killed in electric chair