A queer youth choir in Nashville gives teens a place to feel safe and change the world

For Bee Crowell of Murfreesboro, middle school was horrible. “Every single kid was awful to me every single day,” they said.

Name-calling, physical threats. Crowell hadn’t come out as queer, but “it was assumed. And they weren’t wrong,” they said. Their parents talked to school staff, to no avail.

However, once a week, Crowell had a respite, a creative refuge where they were greeted with hugs: Major Minors, the youth division of Nashville in Harmony, a choir for LGBTQ+ people and allies. It’s one of a handful of youth queer choirs in the country that combine artistic expression with creating community and change — letting LGBTQ+ teenagers literally raise their voices and be heard.

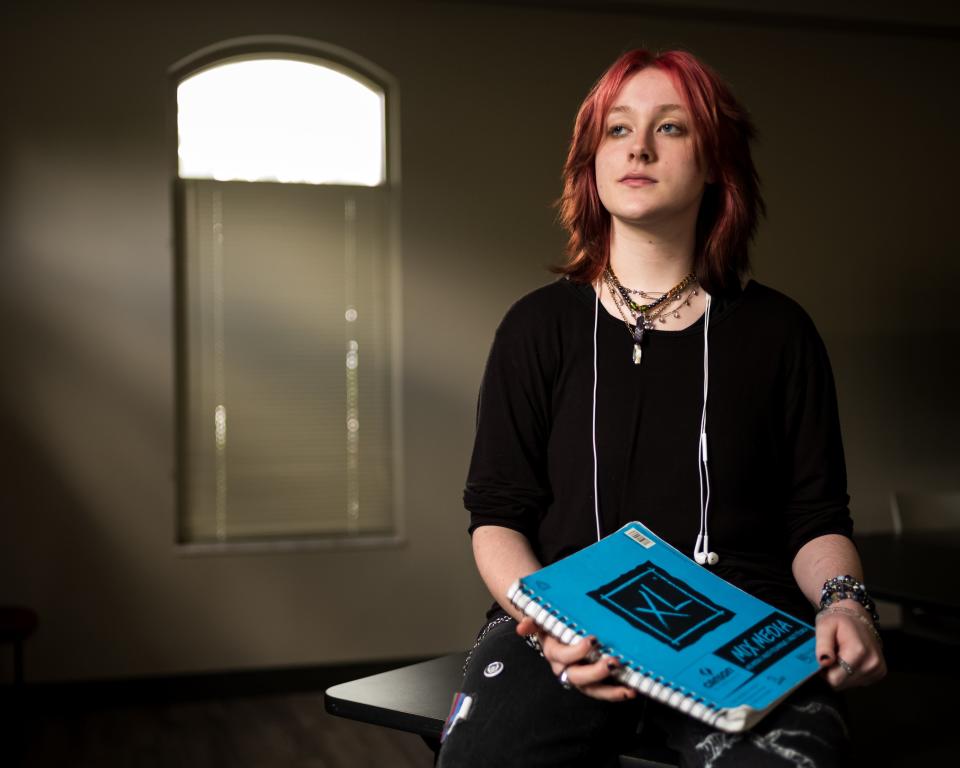

Crowell, now 17 and a rising senior, sat in a Murfreesboro café with their dad in early August. They wore all black, including a T-shirt of ‘80s goth band Siouxsie and the Banshees and jeans they hand-painted; their Manic Panic red hair brought out their pale blue eyes.

When Major Minors performs, they often glitter in sequined jackets like disco balls. But the glow the choir casts starts well before the concert.

“I would go to this practice with kids who were also struggling at school, and who also felt put down, and they would just be there for each other,” Crowell said.

That support is a big part of why Major Minors exists.

“Our mission is to build community and create social change, and I like to go even further and say create safe spaces where the kids are not afraid to express themselves and be themselves,” said artistic director Joe Lee. “Music is just a way to accomplish that.”

In fact, Major Minors doesn’t have auditions: Anyone 12-18 is welcome to participate.

LGBTQ+ choirs have always had this larger social mission. The first choirs started in the mid-‘70s as part of the gay and women’s liberation movements. Today, about 185 LGBTQ+ choirs in North America belong to GALA Choruses, an umbrella group, director Robin Godfrey said.

But only about half a dozen serve youth.

The suburbs, exurbs and country can be especially hard places to be queer, trans or questioning. Some Major Minors members drive almost an hour each way to participate, Lee said.

In Crowell’s hometown, the city denied future event permits to the Pride festival after a 2022 drag performance went viral. In late July, the festival finally announced a new location at the local university’s coliseum.

At one point, Crowell’s dad Garrett drove seven kids from Murfreesboro to Nashville. “Some of my favorite memories actually are of them all singing in the car on the way back from practice,” he said.

You don’t have to be a man to sing tenor

As choirs go, Major Minors does things a little differently. A good chunk of each two-hour rehearsal is devoted to exercises in gratitude, self-reflection and community-building. In one exercise, the choir wrote systems of oppression on a flowerpot, then smashed the pot.

Lee chooses pop and musical theater repertoire that lets the members express fear, loneliness and hope, such as “You Will Be Found” from the musical “Dear Evan Hansen.” At summer camp, Major Minors and two other queer youth choirs wrote a song with a coach, about needing to leave a place that has both “held and hurt” them.

“Those are poignant songs for any kids, but especially queer kids,” Lee said.

Then there’s the singing itself. Voice parts have traditionally been gendered — we call grown men with high voices “countertenors,” not altos or sopranos. But they don’t have to be, and there’s a growing movement in choirs to stop assuming that gender equals vocal part.

Before Lee, when Crowell encountered a new conductor they’d be put in the alto section, because they were assigned female at birth. But “I actually sing tenor,” they said, as does their mom. They have loved the low notes ever since their geeky family sang They Might Be Giants in the car.

Lee leaves voice part choice up to the singer. “I allow the kids to sit with the voice part they identify with. If a kid tells me they’re a tenor, I never say they’re not,” he said. Maybe they’ll sing the same musical line an octave up or down.

It’s important because how you sound can connect deeply to who you are. Some trans people feel like their singing voices don’t reflect their gender. If a singer wants, Lee will work with them on vocal exercises to explore and expand their range in the direction they want.

Conducting Major Minors has changed how Lee sees his musical work of more than two decades and connected it with his master of divinity studies.

With all the groups he’s led, in churches and cities, “While we do want our work to serve the music, what’s really important is building community, creating social change and making people feel safe,” he said. “Those are the important things to me now.”

Singing through fear

It’s a difficult and disempowering time to be a LGBTQ+ teenager in the South. Most Southern states have passed laws curtailing gender-affirming care and discussion of queer and trans issues in schools. Lee chose not to share the group’s rehearsal location, for safety.

“Kids’ rights are in jeopardy, and they can’t even vote for their own rights. It feels pretty hopeless,” Crowell said. “I feel a lot of the time like there’s nothing I can really do to make a change.”

Major Minors occasionally sings unannounced in public places, like Nashville’s Parthenon. “It’s scary,” Crowell said. “But we do it anyway. Because we want people to see us.”

When Crowell expressed optimism, it was in negatives. Their life will eventually get better “because it has to.” The applause Major Minors gets reminds them “that there are people who aren’t terrible and hateful and aren’t there to shame us,” they said.

But it’s more than that. At one concert, a woman in the front row started crying. Afterwards, she told each singer how much she wished she could have had a queer choir when she was young.

That’s what makes Major Minors so important, Crowell said.

“To be able to get on stage and do something that is yours and that you’re doing together with other kids who are like you, and making that impact on somebody — it feels great to be able to do anything,” they said.

Danielle Dreilinger is an American South storytelling reporter and the author of the book “The Secret History of Home Economics.” You can reach her at ddreilinger@gannett.com or 919/236-3141.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Nashville queer teen choir champions community, safety, social change