Racist housing clauses are still on the books in Bloomington. How to check your own deed

Editor's note: In honor of Black History Month, The Herald-Times is publishing Black stories, both current and historical, throughout the month of February. A new installment will be published each weekday.

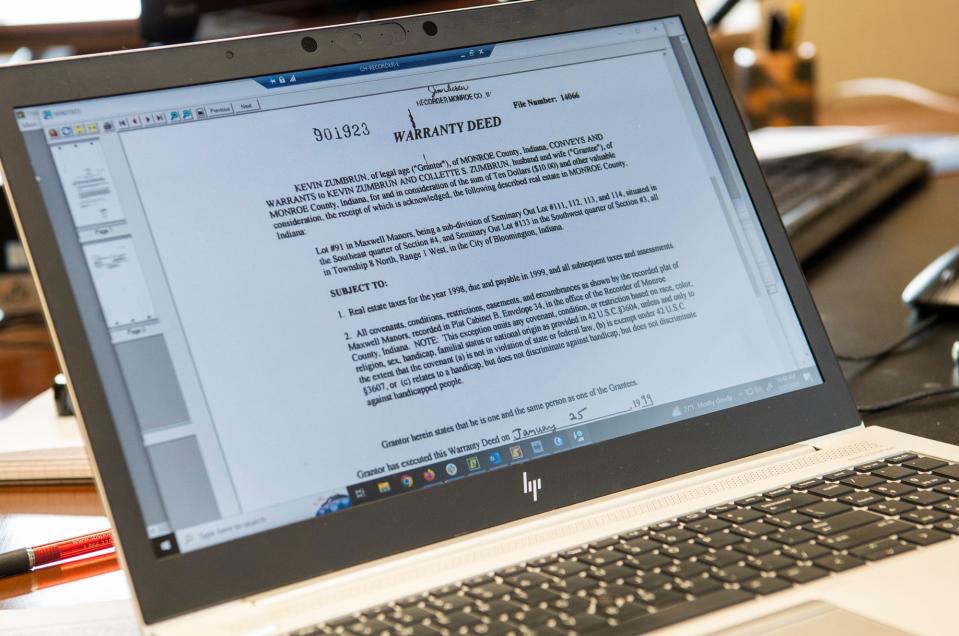

As a homeowner, when's the last time you looked at your deed? It's not a trick question, and there's no shame in admitting the thought has rarely, if ever, crossed your mind. As many employees in the Monroe County recorder's office are quick to point out, there's really no reason for property owners to do so.

In fact, homeowners typically don't even have a copy of their deed on hand; instead, this historic stationery, some of which traces property ownership back 100 years, remains just that — stationary inside a county office on the courthouse square.

But now, as part of an ongoing project, county personnel are asking property owners to take a look at their property's housing documents. They may be surprised, and disturbed, at what they find.

Read the full collection:Black History Month in Bloomington: what to know, where to go and who to follow

In hundreds of property deeds in Monroe County, hidden alongside talk of utility easements and front yard lines, there's another clause, which past and future property owners were tasked with abiding by: "It is agreed between the above parties that none of above tract of land is to be ever sold to Colored People."

That particular covenant is from a property deed from 1912, the earliest record of this sort of racially restrictive language in the county. This sale also is notable for its buyer and seller. Former county commissioner, Jacob W. Miller, sold about 15 acres — from North Kinser Pike and West 17th Street, all the way to College Avenue — to the Showers Brothers Company, famous furniture tycoons.

This deed was not an outlier. It likely isn't even the beginning of this pervasive practice in the county. For several decades, covenants like this were commonplace. Between the early 1900s until the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act, Monroe County was one of countless places in the United States where property titles were heavily restricted on who could buy, or even occupy, land.

Despite this practice being unenforceable for several decades now, these covenants remain on historic housing documents. The process for removing them is a little difficult. It's part of the county recorder office's ongoing project to raise awareness of these covenant so homeowners can repudiate, or legally renounce, this language from each local deed.

"Some of these people don't even know that the language exists in their previous deed. So, one, we want to make sure the language doesn't get carried forward. Also, that (property owners) don't have an unpleasant surprise and get blindsided when they discover any of that language," county recorder Amy Swain said. "Who knows how a buyer might react if they knew that that existed? So, it's a way to address the issue before it becomes a problem."

Deputy county recorder Jason Funk, who has tackled most of the research, agrees.

“Even though it's unenforceable (and) illegal, it can still have a chilling effect on a buyer. The words still have an effect,” Funk said.

County personnel and volunteers from the Monroe County History Center have been collecting all of the historic housing deeds with these covenants. In this year-long process, what they found was startling — nearly a thousand instances of racially restrictive language, and the count is far from finished.

Monroe County traces restrictive housing covenants of the past: Here's where it was most prevalent

The countywide project began at the end of 2021 under the helm of Eric Schmitz, then-county recorder. He first had the idea to dig into the county's records when the topic of discriminatory governance was brought to the table at a national conference with other recorders.

“The simplistic approach is to say, ‘Well, these are offensive. Let's get them out of the public record.’ But unintended consequences can arise. I mean, first of all, you're not doing history any favors by ignoring it," Schmitz said.

There's also logistical concerns. If any element of these housing documents was removed without going through proper legal channels, it could result in a break in the chain of title, which can create a slew of complications for the homeowner. At the conference, a slate of corrective approaches was introduced, prompting Schmitz and other recorders to debate the best approach for their respective communities.

“Indiana has went with a repudiation approach so that, in a new document, they can include a clause that says any existing racially offensive covenants are null and void, so that it’s acknowledged right here in writing and acknowledged by all parties to the transaction,” Schmitz said.

This way, it doesn't erase the history but reaffirms that current recorders and property owners are aware this sort of restriction has no place in their deed.

What does a racially restrictive clause look like? While it all boils down to the same sentiment, these clauses went through several iterations through the early to mid-1900s. Sometimes, it was specified what nationality or heritage was explicitly restricted from ownership. For one area, a subdivision called Smithwood in the eastern part of the city near Third Street, anyone who was Black, of mixed race or of Chinese or Japanese descent was prohibited from owning a house or living there.

Another subdivision, Maxwell Manors, was "forever restricted to members of the pure white race," according to housing deeds. As Jakobi Williams, chair of IU's African American and African Diaspora Studies and expert on 20th Century U.S. history, noted, this kind of specification at the time often excluded people who could now be considered "white," such as those with Jewish, Slavic or Polish heritage.

As Funk estimates, the idea of racially restrictive housing covenants did not crop up in a vacuum in Monroe County. Rather, as some of the earliest instances of this language can be traced back to the East Coast in places such as Baltimore, these covenants were carried with people who moved.

"Everybody’s moving West, establishing new cities. Those rules and ideas from these kinds of people are going to follow that population,” Funk described.

Some of these new residents would use copies of their old deeds from the East, which had this language, as a template when crafting new deeds here. Often, it was also real estate agencies based in Eastern cities that would suggest this clause to Midwest property owners.

In Monroe County's case, it was both property owners and real estate agents who standardized and used this language in their deeds.

"It's a small group of people that had the money to do it. They had the interest to do it," Funk noted. "We're looking at flippers, so we're looking at people that buy up land and then sell it."

These racial covenants were most prevalent directly south of the Indiana University campus, where most subdivisions were being created.

The practice of racial covenants was put to the test in a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court case, Shelley v. Kraemer, when the Shelleys' purchase of a home in St. Louis was disputed by the neighborhood's white residents. The justices sided with the Shelleys, noting that a restrictive covenant couldn’t be legally enforced by the courts because it violated the equal protection provision of the 14th Amendment. However, restrictive covenants would continue to be socially enforced in cities and suburbs across the U.S. until they were directly outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act.

But just because the deed language was no longer legal doesn't mean the practice vanished overnight.

Though covenants now illegal, IU expert notes 'practice is still there'

From both academic study and personal experience, Williams knows housing continues to be rife with discrimination.

“Even though the racial covenants were illegal in 1948, the practice continues today," Williams said. "And that practice is by the residents themselves, by some people who participate in a real estate agency market, and also by lenders — they only give loans to certain places and so forth — and then by homeowner associations.”

Directly after the landmark Supreme Court decision and the 1968 Fair Housing Act, neighborhoods were not automatically integrated across the United States. Rather, they found new ways to keep people of color out, such as using codified language.

"For example, if I want to move into a neighborhood that has a homeowner association — say, in Carmel — they can decide whether or not I can live there. They would not say exclusively, 'You can't live here because you're Black or Japanese or an immigrant' or whatever. They have arbitrary language that says 'You just don't fit the mission of our neighborhood,' without ever telling you what the mission of the neighborhood is. It's really arbitrary language. So they're very discriminatory in that way,” Williams said.

People of color continued to also face redlining, which was when a lender denied credit to individuals based on race, ethnicity or other discriminatory factors.

"Because of those racial covenants, because of the ways in which redlining operated, many of these residents may have not had any personal animosity or even been racist themselves, but were just trying to protect the integrity of their homes, the property value of the home, the asset of their homes," Williams said.

If several people within the housing market keep telling residents their property value would take a dive if a person of color were their neighbor, that resident is less likely to help diversify the neighborhood, Williams noted.

Williams references his own experience buying a house in a planned residential community in California in the early 2000s. As soon as he and his wife began inquiring about the housing models, an employee automatically dismissed them.

"The person looked us in the eye and said, 'You can't afford a home over here.' How do you know what we can afford? Is there an application you want me to fill out, so I can maybe see what I qualify for? Plus, you don't give out mortgages, so how do you know what I qualify for? This person would not give me an application," Williams recalled.

Eventually, the employee said Williams and his wife were too young to think about purchasing a house there. However, when friends of Williams, who were around the same age but were white, entered that same office, they were greeted very differently by the same employee.

"She's like, 'Hi, how are you doing? Wonderful to meet you. Welcome to the neighborhood. This is going to be your new neighborhood,'" Williams described, noting he later sued the company and settled out of court over the incident.

Around 10 years ago, when he and his wife were moving, their former real estate agent did not want to show them places in Carmel. His sputtered reaction when Williams directly asked him why not? "'My daughter lives there,'" Williams recalled the man saying.

Williams later moved to Carmel with his wife, where they became the second Black family on the block. About two years after moving there, Williams noted several people of color began moving into their neighborhood while his white neighbors began moving away. But at his local HOA meetings, where he is often the only Black person, this same sort of conversation takes place even today.

"That's no racial covenant, but the practice is still there. 'We don't want certain people in our community because we don't want our property values to go down. We don't want renters. We want to keep section 8 out of here' and all this coded language about what's taking place," which Williams said targets young people and people of color.

How to check your own property for racial covenants, use new interactive tool

So far, the recorder's office and the Monroe County History Center have found around 900 deeds — totaling around 600 properties since some deeds are tied to one another — with racially restrictive language.

Pouring through a hundred years' worth of housing documents is exhausting work, Funk said. Even with a year's worth of research, it will take a long time to collect and repudiate all of these deeds. Homeowners can be proactive by calling up the recorder's office and checking on their own property records. People can request a copy of their deed at the recorder’s office, with each page costing about $1.

If they find a racial covenant, the recorder's office can begin the repudiation process as well as potentially add the property to their interactive webpage. This webpage, launched just this week, provides a detailed explanation of the historical context behind what racial covenants are and how they were used in Monroe County.

One unique part of this resource is an interactive map feature that provides a way for online users to look around the county and glean information about these covenants, such as where exactly these properties are located and what restrictive language they used. The interactive tool can be accessed at http://indianarecorders.org/go/monroe.

County personnel envision this map as a key educational tool for the community to have a local lens into how discrimination was propagated in the not-so-distant past.

"Sometimes language still carries forward even though it's not enforceable and it's illegal because we're just copying and pasting," Swain described. "So that's why it's so important to educate the public, so that someone who has lived in their home for 50 years – we just had a property transferred the other day, they have lived there for more than 50 years – that language doesn't carry forward.”

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Bloomington, Monroe County housing deeds still contain racist language