Racist humor empowers white supremacy, Raúl Pérez argues in book, "The Souls of White Jokes"

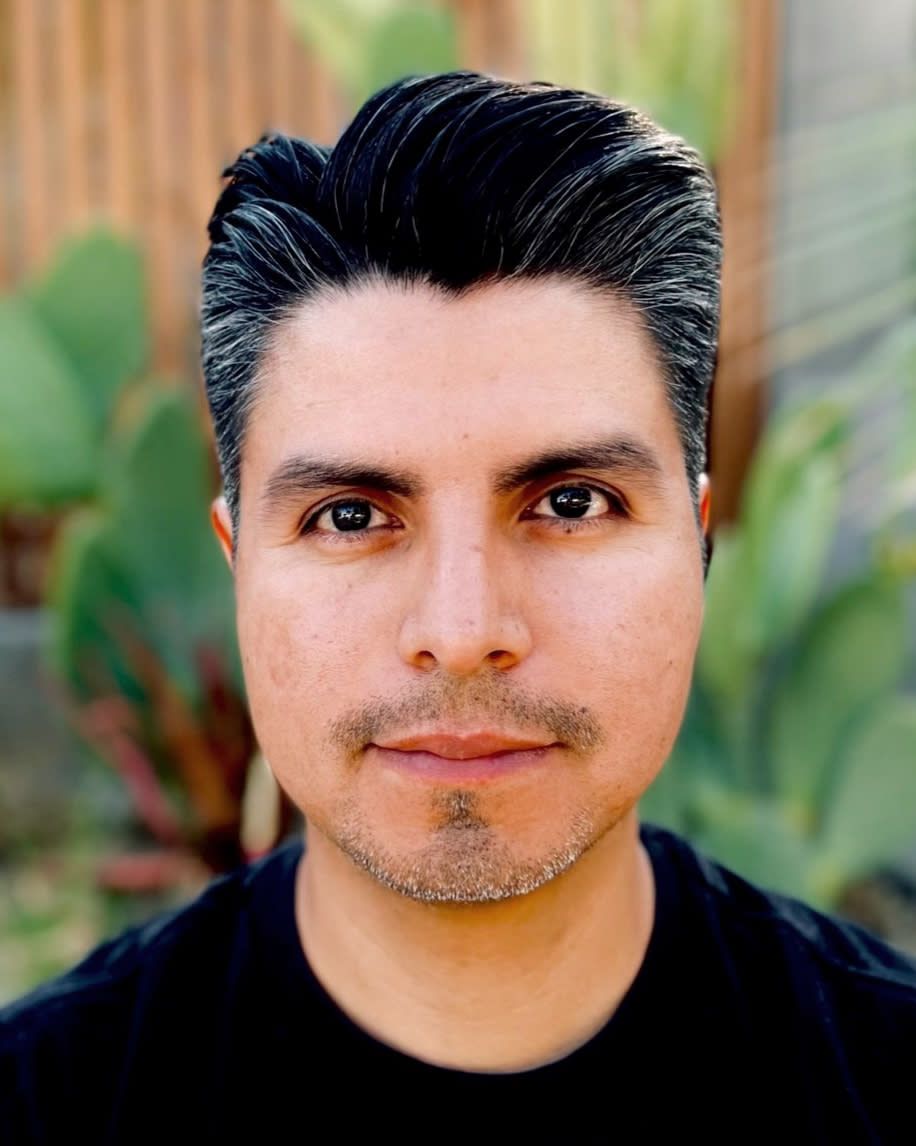

Author and sociologist Raúl Pérez attended a diverse university in California that promoted mutual respect among students, "yet after hours, in the dorms, I saw many boundaries tested with racial humor."

“We were sociology majors, we were taking ethnic studies courses," Pérez said, "and here we were in an environment where people were free to make racist and offensive jokes."

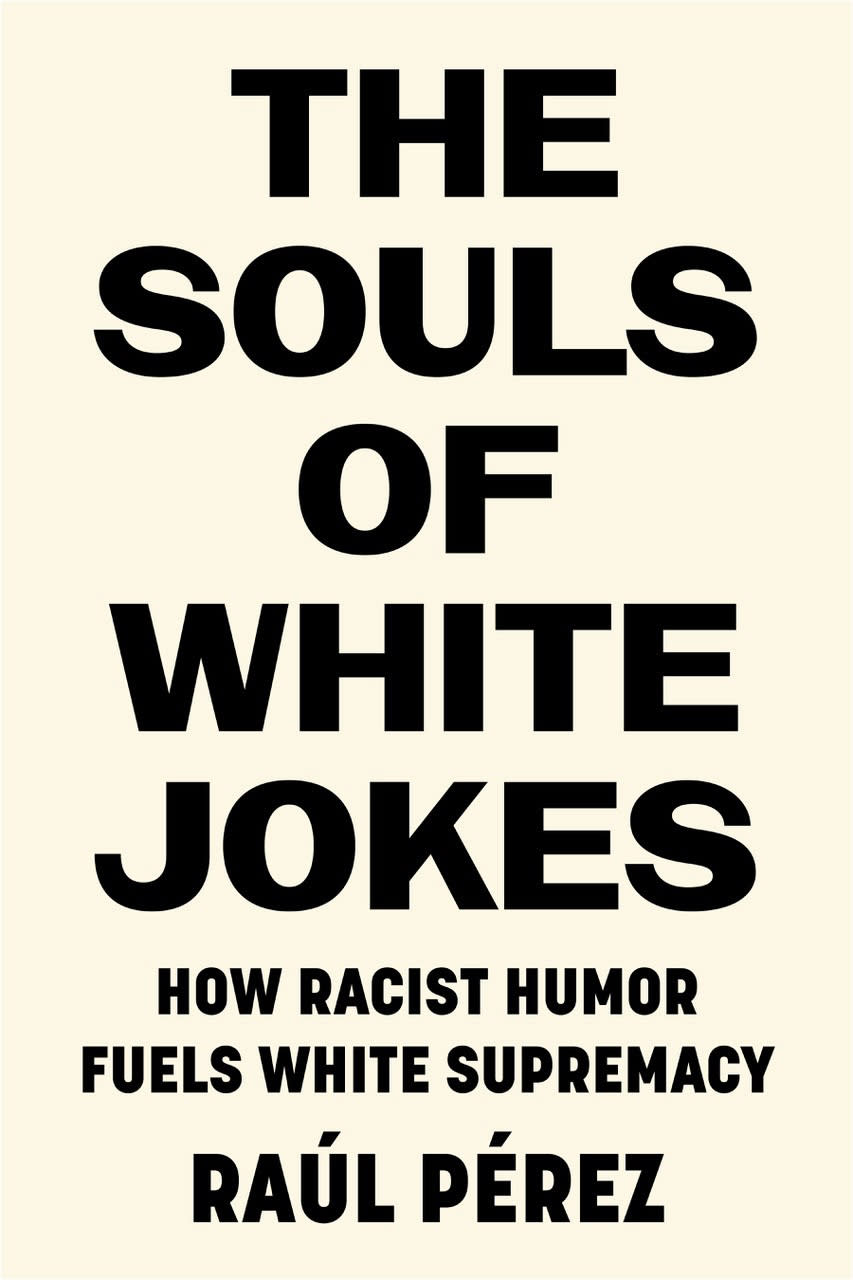

Convinced that there was more behind such experiences than “just jokes,” Pérez embarked on academic research on the intersection between humor, race, power and inequality. Now he has released his first book, “The Souls of White Jokes,” which aims to show how racist humor fuels white supremacy.

He also shows how pervasive its use is — from media figures and politicians to law enforcement and far-right groups.

Pérez, assistant professor of sociology at the University of La Verne, in California, knows that humor is often a form of release from everyday pressures. What he examines in his book, whose title recalls W.E.B. Du Bois’ seminal essay, “The Souls of White Folk” (1920) is how the stakes around humor change when the jokes are racist.

Pérez argues that racist humor goes well beyond the entertainment world, and that it is actually dangerous in certain segments of society. There are significant patterns, for example, of law enforcement agencies across the country circulating racist jokes among themselves.

“Whether it is the LAPD or the Border Patrol, we see racist jokes correlating to how people are being treated by these officers,” Pérez said. “These are not just jokes, these are rituals that allow for mistreatment and violence against people the police view with ‘amused racial contempt’ … If police culture allows for the dehumanization of certain groups, then what do we expect when the police interact with the people they view as subhuman?”

In his book, Pérez details how alt-right groups use humor to promote their ideologies and recruit new members. “Memes like Pepe the Frog have been used to attract audiences; the alt-right has been weaponizing racial humor in a socially destructive way for years.” The suspect who carried out the mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, Pérez pointed out, urged white supremacists to use memes to get attention to their cause.

Pérez also writes about how racist humor has been used in the political arena, particularly during the Obama era, when pejorative racial depictions of the president were common.

Humor can be much more than making people laugh and feel good, Pérez writes. It can be used to reinforce boundaries around inclusion and exclusion, empower ideologies and harm marginalized people.

“In racial jokes, there is this theory of ‘amused racial contempt,’” Pérez said, “which I define as feeling pleasure in regarding others as inferior, with pity, or with contempt. It’s basically the idea of finding joy in treating others as worthless.”

This concept has deep roots in American history. Minstrel shows mocking African Americans were our country’s original pop culture, Perez writes, and the most popular form of entertainment during the 19th century. This style of open racial ridicule lasted for over 100 years. “After the civil rights movement, racism was finally seen as bad,” Pérez said. “Then racial humor became officially taboo, and unofficially a forbidden pleasure. Yet it has never gone away.”

Racialized humor has taken many forms over the years, from comedian Bill Dana’s stereotypical “José Jiménez” character in the 1960s, to Howard Stern mocking the death of Selena (1995), to George Lopez satirizing the biases of Mexican American families (2017).

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, professor of sociology at Duke University, said that “Racist humor is a reflection of our culture,” and that the country is living through a backlash against what critics call “woke” or “cancel culture.” “Those at the top of our hierarchy are saying that they want to be able to make jokes about women, the LGBTQ community and people of color... it’s similar to what the country went through in the 1980s, only then it was a backlash to so-called “political correctness.”

In Bonilla-Silva’s view, racial jokes against people of color will not necessarily go away.

“Irish jokes, Polish jokes, they have faded from the culture because the social standing of these groups has changed," Bonilla-Silva said. "For Blacks and Latinos, it will be harder to escape such racism, because we cannot assimilate away our skin color or distinct heritage.”

Like other Americans, Latinos are not strangers to racialized humor. According to the Pew Research Center, about half of Latinos report hearing racially insensitive jokes or comments from Latino friends or family, whether about other Latinos or about non-Latinos.

Indeed, the current social climate has impacted how Latino comedians perform and interact with audiences.

For comedian and actress Aida Rodriguez, comedy comes with a sense of personal responsibility. Her routines often draw on her family and heritage, and there can be a fine line, she observed, between mentioning her Dominican father in her act, and appearing to mock Dominican or other Latin men in the process. “I often run jokes through my rinse cycle a few times, I want to be sure I check in with my humanity when I am being funny,” said the star of the comedy special “Fighting Words” on HBOMax. “For so long, it was normalized to punch down at people who are historically a punchline.”

Rodriguez has not shied from tackling racism, including colorism within the Latino community in her humor. “There is a lot of anti-Blackness in our (Latino) culture,” she said. “I think it is important to hold a mirror up so we can be better.”

“To me, it comes down to self-esteem,” Rodriguez said about racial and ethnic humor. “We have to learn to talk about ourselves and others, because the truth is that people who feel good about themselves don’t go around sh---ing on other people.”

Comedian Carlos Mencia believes that the debates over whether certain topics are off-limits has been good for comedians. “You can make a joke, if you can defend it. If you make a provocative statement, you have to be prepared for the response,” he said. “I personally don’t censor myself.”

Mencia sees limited value in comedians making fun of ethnic groups or mocking different cultures. “I want to make every single person who comes to see me laugh. I want to make them happier than before we encountered each other. Comedy should be a unifying factor; the jokes that make everyone laugh are the best ones.”

For his part, “The Souls of White Jokes” author Pérez believe that things would have to significantly change in the U.S. before people can joke across racial lines without hurting or offending one another. “Without a massive effort toward real structural equality,” he said, “racial jokes will continue to sting, because they reflect that materially, economically, some groups are less valued in society.”

“A superficial or theoretical sense of racial equality does not make it ok to trade jokes across color lines,” Pérez said. “Until we have true racial equality, we are not there yet.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.