The Racist Panic That Thrust Michael Jordan Into the Debate Over “Sneaker Murders”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

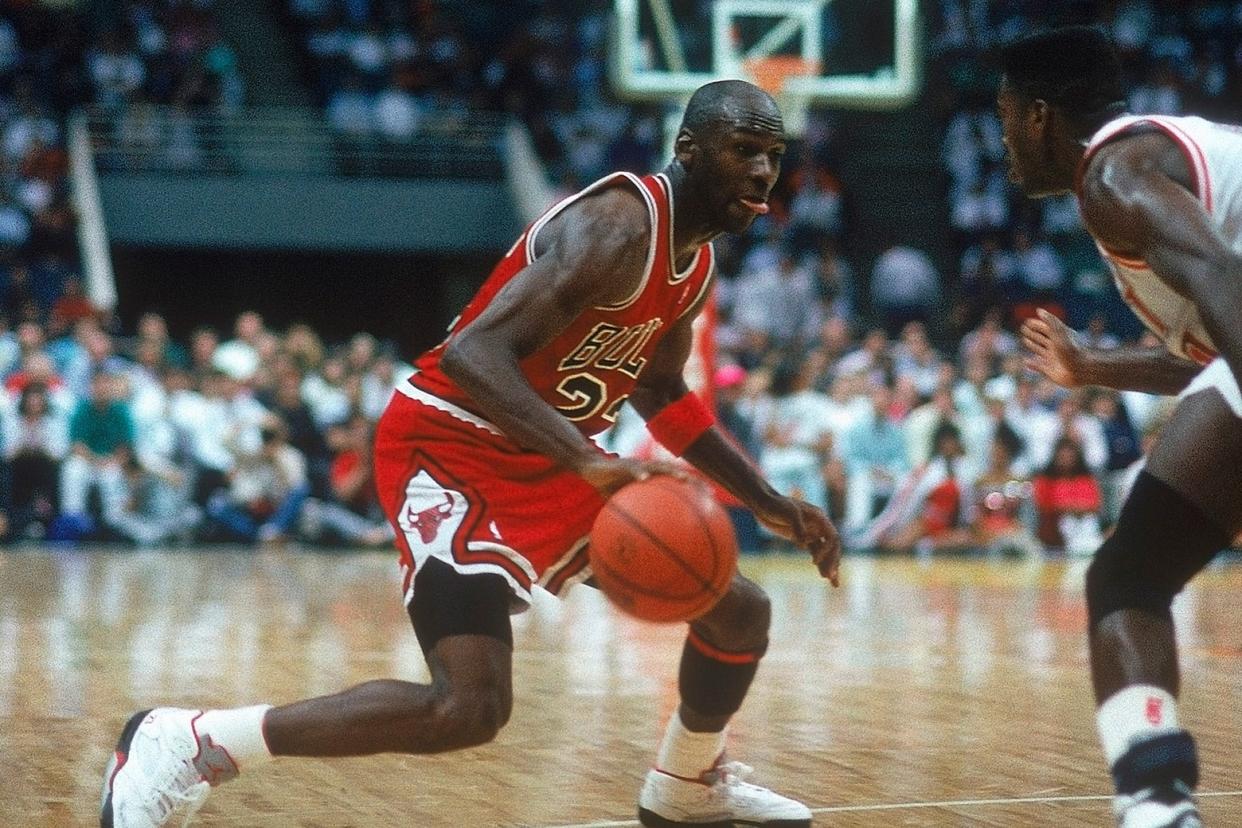

For a moment, Rick Telander thought, Michael Jordan looked like he might cry. In 1990 the senior writer from Sports Illustrated approached Jordan before practice and told him about the murder of a 15-year-old Black boy named Michael Eugene Thomas. About a year earlier, the ninth grader from Anne Arundel, Maryland, had paid $115.50 for a pair of Air Jordans. The young fan worshipped the Chicago Bulls star and the shoes embroidered with his silhouette. Every night, he took his sneakers out of a black shoebox and polished them proudly. But about two weeks after he bought the Air Jordans, schoolchildren found him barefoot in the woods, strangled, face down in a puddle. Shortly thereafter, police charged his 17-year-old “basketball buddy” James David Martin with first-degree murder.

Jordan sighed. He didn’t know what to say. Sitting in a private room at the team’s suburban practice facility in Deerfield, Illinois, he struggled to process an incomprehensible and heinous crime. “I can’t believe it,” he said. “Choked to death. By his friend.” Jordan asked Telander if he knew about similar crimes. Unfortunately, Telander explained, he had read numerous accounts like this one. In his jarring story, he wrote about the “frightening outbreak of crimes among poor black kids” assaulting and sometimes killing one another for sneakers and Starter jackets. After collecting stories from Chicago newspapers and Sports Illustrated’s national news bureau, Telander concluded that the crimes were not new but “the pace of the carnage [had] quickened.”

In April of that year, New York Post columnist Phil Mushnick, a cynical crusader disillusioned with the greed and hypocrisy of sports, blamed Nike spokesmen Jordan and Spike Lee for a wave of inner-city “sneaker killings,” claiming that the crimes had morphed into an epidemic. Shortly thereafter, Sports Illustrated published Telander’s sensational cover story, “Your Sneakers or Your Life,” which created a simple narrative: Black kids killed other Black kids for shoes worn by the great Black basketball hero.

For the first time in his career, people began questioning Jordan’s influence upon Black youth, demanding that he account for the sneaker murders. The public scrutiny would force him to confront his own role in the nation’s racial divide. Despite all the praise he had received for supposedly transcending race, this episode sparked Jordan’s realization that he could never really evade the burden of representing Black America.

In Chicago, where Telander lived, the city papers devoted copious amounts of ink covering two phenomena: the ascendance of Jordan and a rising wave of violent crime. Between 1989 and 1990, Chicago’s murder rate climbed 14.5 percent. City aldermen decried a “murder epidemic” that afflicted Chicago’s youth. One survey found that 74 percent of Chicago school students had witnessed a murder, shooting, stabbing, or robbery, and nearly half of them had been victims themselves. For middle-class Americans far removed from the country’s urban centers, cities resembled lawless war zones. “Violent crime,” Newsweek reported, “much of it drug-related, is on the rise in virtually every city in America. Inner city neighborhoods are disintegrating in an escalating cycle of mayhem.”

Increasingly in the 1980s, in Chicago and other cities, white reporters treated violent transgressions like spectacles, embellishing an image of a Black underclass that produced roving hordes of violent juvenile delinquents. “When the sun sets on Chicago’s West Side, the armies of the night come out to play,” Paul Weingarten wrote for the Tribune. “People in the neighborhoods retreat into their homes—or if they’re brave to their porches—and wait. Out in the night, a new order takes shape. It is an alien world, strange and incomprehensible. A world where junior-high kids carry shotguns, and no one ventures out unarmed.”

The alarm over sneaker crimes reflected a growing anxiety over “juvenile superpredators—radically impulsive, brutally remorseless youngsters, including ever more pre-teenage boys, who murder, assault, rape, rob, burglarize, deal deadly drugs, join gun-toting gangs, and create serious communal disorders.” Columnists accused apparel companies of encouraging “violent lifestyles by directing advertising campaigns toward black urban teens.” Without any evidence, they suggested that such marketing was an effective strategy because basketball was “the sport of choice among urban drug dealers.” Like Mushnick, John Leo, a conservative writer for U.S. News & World Report, argued that Nike exploited impoverished inner-city Black youth who could not afford Air Jordans. Some of them legitimately worked and saved for the shoes, Leo wrote, but others acquired them illegally or paid for them using drug money. Using coded language, Leo suggested that Black people were more susceptible than white people to advertising that emboldened them to commit crimes. “The line ‘Just Do It’ means one thing to the middle-class, and something else to people in the ghetto,” he said. “To the middle-class, it means get in shape, whereas in the ghetto it means, ‘Don’t have any moral compunction—just go out and do whatever you have to do in your predicament.’ There’s an immoral message imbedded in there.”

Liz Dolan, Nike’s director of public relations, combated charges of exploitation by arguing that sneaker crimes were not a result of advertising. Rather, the root of the problem stemmed from income inequality and a growing sense of “hopelessness” in the inner cities. Furthermore, she told Telander, Nike’s endorsers were excellent role models. Who was a better example for children than Michael Jordan? “What’s baffling to us,” she said, “is how easily people accept the assumption that black youth is an unruly mob that will do anything to get its hands on what it wants. They’ll say, ‘Show a black kid something he wants, and he’ll kill for it.’ I think it’s racist hysteria.”

In response to Mushnick, Spike Lee wrote an op-ed in the National, a short-lived daily sports paper. Lee suspected that the New York Post writer who started the furor against him and Jordan had “a hidden agenda” couched in “thinly veiled racism.” He wanted to know why Mushnick, who had never given so much attention to poor Black kids before, suddenly became interested in their plight now. Further, Lee maintained that his commercials with Jordan were not exclusively directed toward Black youth. Car theft was a major urban crime too—millions of cars were stolen or looted annually—but no one called for Jordan to stop doing Chevy commercials.

Unlike Lee, Jordan never publicly said that the attacks on him stemmed from racism, but he clearly felt that he was targeted in a way that white athletes were not. “It’s kind of ironic that the press builds people like me up to be a role model and then blames us for the unfortunate crimes kids are committing,” he said. “Kids commit crimes to get NFL jackets, cars, jewelry, and many other things. But nobody is criticizing people who promote those products. I also don’t hear anybody knocking other sports stars like Larry Bird and Joe Montana, who also endorse their brand of shoes and other sporting goods.”

Implicitly, Jordan suggested that blaming him for sneaker crimes was unfair because reporters failed to provide precise numbers when writing of murders involving products bearing his name. How many teenagers were killed for wearing expensive sneakers? And how many of them wore Air Jordans? Did anybody know? In interviews with police officers, Telander tried to answer those questions and received varying answers. The Atlanta police estimated that over a period of four months, they encountered more than 50 mugging cases involving sportswear. A Chicago police sergeant estimated there were 50 incidents involving jackets and about a dozen shoe crimes each month. But Richard Lapchick, director for the Center for the Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern University, argued that reports about sneaker murders were grossly exaggerated. A month after Telander published his story, Lapchick told an Associated Press writer that since 1983, there had been only nine documented murders involving sneakers.

Yet Telander’s 4,000-word cover story, bolstered by television news reports, gave the impression that “an unconscionable number of killings have actually occurred over status-symbol sneakers, pro or college team jackets, and major league baseball caps.” In the second week of May 1990, when Sports Illustrated’s subscribers opened their mailboxes, they found the most provocative cover of the year: an illustration of an armed Black man pointing a revolver into the back of another man wearing a satin Starter jacket as the gunman snatched the victim’s Air Jordans.

Telander’s story did pose an important question: What could explain the violence over expensive shoes and jackets? Elijah Anderson, a distinguished sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, suggested that the crimes were linked to larger forces of racial inequality. “The uneducated, inner-city kids don’t have a sense of opportunity,” he said. “They feel the system is closed off to them. And yet they’re bombarded with the same cultural apparatus that the white middle class is. They don’t have the means to attain the things offered, and yet they have the same desires. So, they value those ‘emblems,’ these symbols of supposed success. The gold, the shoes, the drug dealer’s outfit—those things all belie the real situation, but it’s a symbolic display that seems to say that things are all right.”

The narratives produced about sneaker killings perpetuated the myth of Black-on-Black crime, a trope rooted in the racist idea that Black Americans were or are inherently more violent than white people. Studies have shown that most violent crimes occur between people who live near one another, which in a residentially segregated country meant that most violent acts were intraracial. And yet no one ever used the phrase white-on-white crime. Instead, news reports about sneaker murders pathologized Black youth as criminals who valued “pieces of rubber and plastic held together by shoelaces … more than human life.” Mushnick insisted, “The only kids dying for the kind of outrageously expensive junk these influential Afro-American role models are pushing are black kids.” But was that true? Did Mushnick or other writers ever investigate whether sneaker crimes occurred in the suburbs? Or did they just assume that sneaker crimes took place only in urban neighborhoods? According to Mushnick’s logic, Spike Lee wrote, “poor whites won’t kill for a pair of Jordans, but poor blacks will.”

In response to Sports Illustrated’s cover story, Chicago journalists and fans defended Jordan. Chicago Sun-Times columnist Raymond Coffey wrote, “What is really senseless here is any suggestion that Michael Jordan has blood on his hands for selling shoes on TV. The people responsible for killing people are the people who kill people.” Joseph H. Brown, a Black man who grew up on the South Side of Chicago during the ’60s, agreed. In a letter to Sports Illustrated, Brown wrote, “None of this is Jordan’s fault. He is not responsible for the moral decay in our inner cities. … The moral revival that is needed to stop this madness must be carried out by families, churches, schools, and community organizations, not by a slam-dunking hoopster.”

Telander did not blame Jordan for the sneaker crimes, even if the magazine cover implicated the Nike pitchman. In fact, in the story, Telander portrayed Jordan as a sympathetic figure suffering from a devastating loss, saddened that Black boys he had never met were killed simply because they wore his shoes. In a sense, then, Jordan grieved with the nation; America’s tragedy was his tragedy, and he mourned as deeply as the real victims’ families. If previously he had believed that being an example of self-help and self-empowerment would help inner-city kids, Jordan now recognized that he could not rescue them. “I thought I’d be helping out others and everything would be positive,” he told Telander. “I thought people would try to emulate the good things I do. They’d try to achieve to be better. Nothing bad.”

In so many instances, observed Chicago Tribune columnist Bob Greene, Jordan appeared completely confident answering questions about various matters outside of basketball. Yet these crimes perplexed and distressed him. What could he do about it? “I don’t have the answer,” he said. “If a parent in a high-crime neighborhood sees his son or daughter going out the door with your brand of shoes on, and the parent is scared,” Greene asked, “what can you possibly say, knowing that?”

“I would tell the parents to tell their kids: ‘Please give it up.’ ”

“Give up the clothing? If the child is being robbed?”

“Yes, give it up. The jacket, the shoes—give it up.” Then, Jordan said something without thinking through the implications. “They should tell the kids I will buy them a replacement.” Not Nike, he insisted, but Jordan himself. He would replace the stolen shoes.

It seemed unrealistic that Jordan could provide insurance to every kid who bought his shoes, but he conceived of his own power in financial terms. He could not imagine joining community activists in the fight against inner-city crime or urban poverty. The only movement he belonged to was the one that hyped the products with his name on them.

And yet the crime stories attached to his name weighed on Jordan, exposing his vulnerability in a way that little else did. He simply couldn’t make sense of the awful violence in America’s cities. “It just makes me so sad,” he said. “The whole thing. Everything is changing.”

Jordan didn’t have the answers to the sneaker murders. And he quickly realized that nothing good came from talking about it. Burying his feelings helped bury the story.

Excerpt adapted from Jumpman: The Making and Meaning of Michael Jordan by Johnny Smith. Copyright 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.