Racist planning decisions led Milwaukee's freeway system along a path of least resistance, with great damage to communities of color

Decades after they were built, America’s freeways are facing a new round of criticism. Some historians believe the urban segments of those super-roads are inherently racist. Transportation decisions made after World War II, they say, inflicted disproportionate harm on people of color in our inner cities. With callous disregard for long-established social networks, planners rammed their concrete slabs through countless minority enclaves, decimating and dividing communities too poor to resist.

That critique has support in high places. In a 2021 interview, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said flatly, “There is racism physically built into some of our highways.”

And now, as planning for the I-94 East-West corridor project continues, some of those same concerns are being expressed.

As someone who grew up during the freeway era and worked summer construction jobs on several of those gargantuan roads, I have vivid memories of solid old houses in the central city first emptied and then demolished. I can still see the day-and-night convoy of dump trucks literally relocating the north side to Milwaukee’s lakefront for the creation of Veterans Park, one load of dirt at a time. The deep ditch they left behind — today’s Interstate 43 — was a gaping wound that disfigured that area of Milwaukee for miles. Even today, the streets bordering I-43 feel like the margins of an amputation.

The inner city had always been in harm’s way, and its situation reflected a double dose of racism. The size and shape of the Milwaukee's inner core were determined in fundamental ways by redlining, restrictive housing covenants, job discrimination, and other practices that combined to keep people of color impoverished and in place.

African Americans were largely confined to the center of town, where all roads meet, including the freeways of the brave new postwar world. When planning for the system began, the damage was compounded. Black neighborhoods were literally the paths of least resistance; low property values and weak political opposition made them easy targets for the transportation engineers.

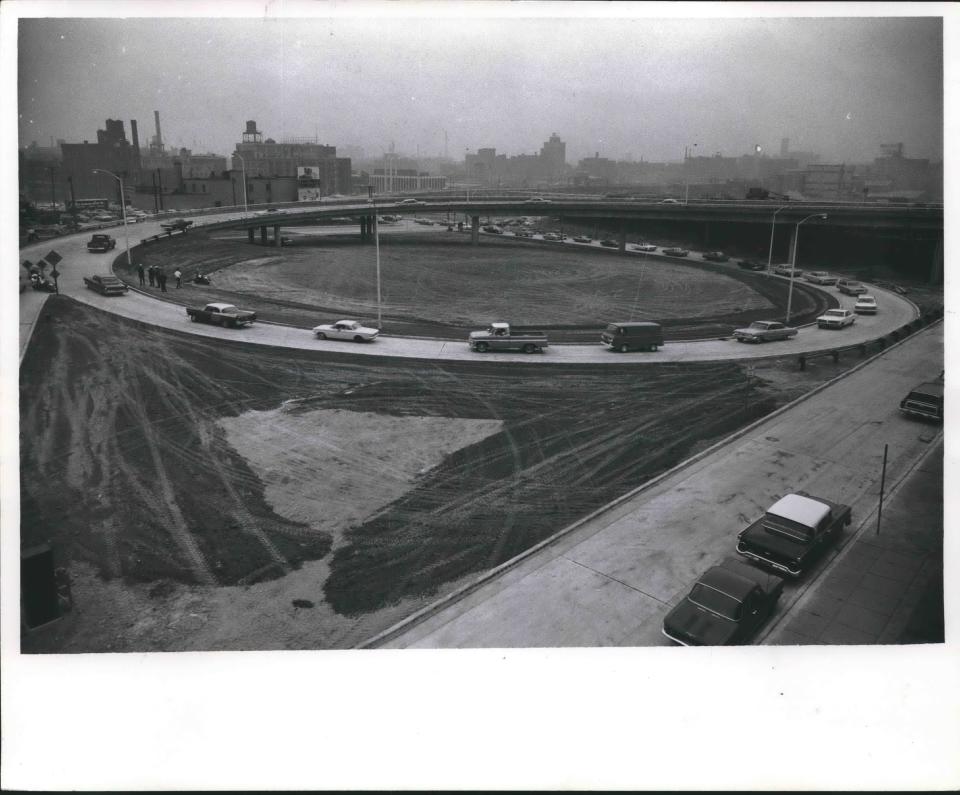

Not that those engineers were openly racist. A year-by-year look at the Milwaukee County Expressway Commission’s annual reports, which began in 1954, turned up no smoking guns. There is, however, at least a whiff of gunpowder in the 1956 report. The original version of the Marquette Interchange, that gigantic knot in the pretzel of Milwaukee’s freeways, was centered on the intersection of 16th St. and Clybourn Ave. In 1956 its north-south axis was shifted ten blocks east to 6th St., a decision, wrote the commissioners, “largely based on land use considerations.” Those considerations were not specified, but it’s obvious that the 16th St. route would have done major damage to the Marquette University campus and the 6th St. alternative led through the heart of the north side —again the path of least resistance.

White engineers working for white commissioners appointed by white politicians saw no reason to consider, much less consult, the Black families they were displacing. Their reflexive racism, however, was imbedded in an even broader attitude. Simply put, freeway planners valued concrete over community. Just as newly hatched suburbanites embraced the novelty of ranch houses on quarter-acre lots and turned their backs on the high densities and concentrated commerce of their old neighborhoods, the planners saw nothing of importance to save along their chosen routes.

In the 1950s, freeways were seen as 'pillars of progress'

It’s hard to believe today, but freeways were once viewed as a panacea. In the 1950s, Milwaukee, like most major American cities, was choking to death on the glut of automobile traffic that materialized after World War II. Convinced that freeways were as vital to the area’s future as water mains and sewer pipes, transportation planners pursued their task with missionary zeal.

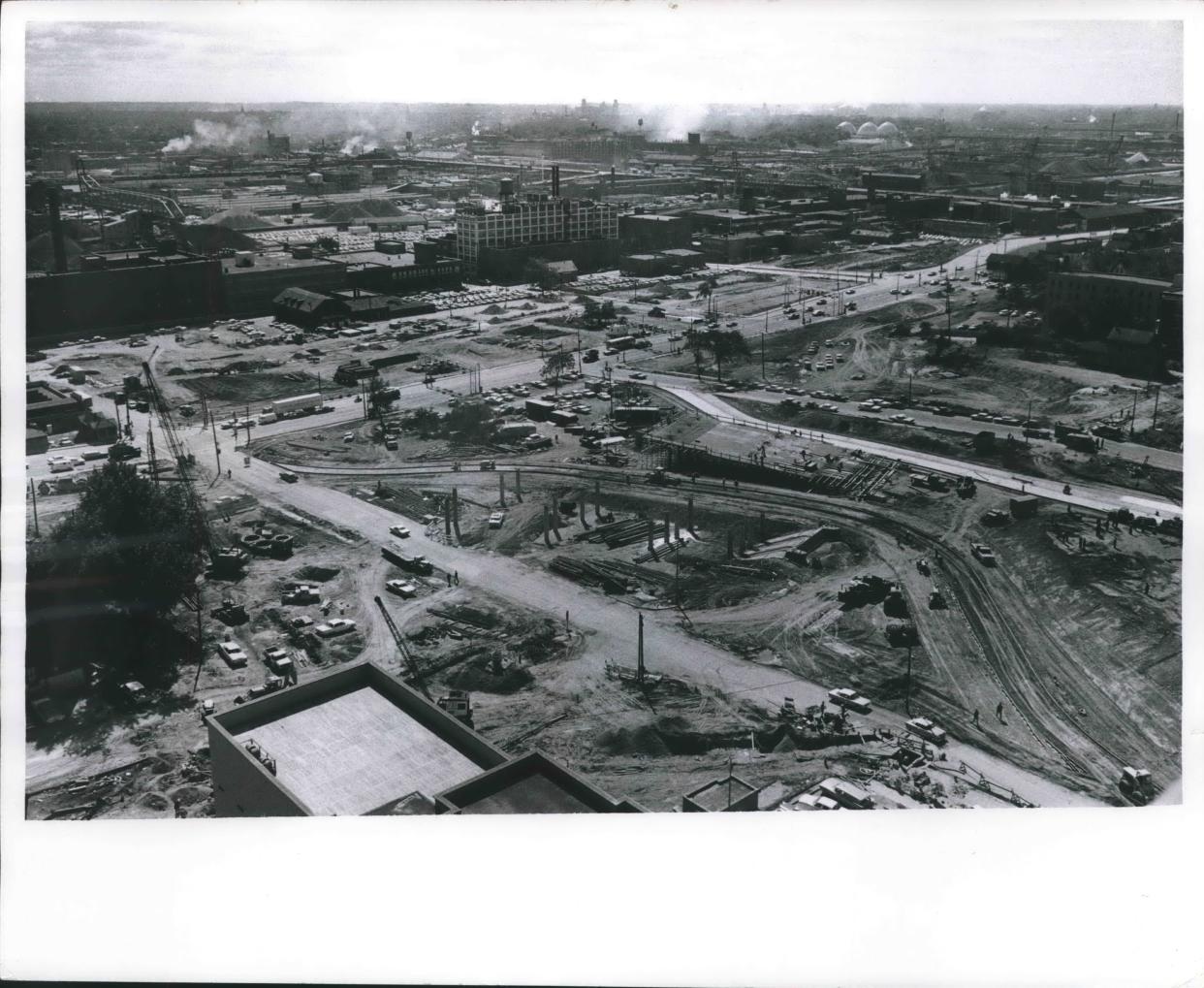

The enthusiasm in the Expressway Commission’s annual reports seems jarring to a modern reader. The commissioners praised the concrete columns supporting freeway overpasses as “pillars of progress” and bowed in wonder before the “spectacular cut-fill operations of giant earth-moving machines.” The collateral damage being done to Milwaukee’s neighborhoods was dismissed with a shrug: “The displacement of families and business activities is a time-consuming process. A certain amount of extended litigation is inevitable.”

When opposition began to surface in the mid-1960s, the expressway commissioners were indignant, slamming their critics as obstructionists who were costing the community good jobs and preventing the planners from carrying out their “transportation mandate.” The reaction was even stronger in 1977, when a federal judge effectively killed the Park West Freeway. The Expressway Commission’s chairman, Gordon King, blasted the decision as “a regrettable step backward for the promotion of commerce and industry in the broad application of meaningful transportation functions designed to bring commerce, the people and their workplace closer together.”

With an irony that was surely unintentional, King denounced the judge’s decision as a case of “George Orwell’s Big Brother thumbing his nose at the electorate.”

In the meantime, the Big Brother of the concrete lobby continued to shred Milwaukee’s landscape. As disastrous as Interstate 94 was for Milwaukee’s north side, any assessment of the damage there should be balanced by an awareness of the freeway’s impact on other communities. I-94 probably did even more damage to the south side, simply because that district was more densely settled, brimming with Polish flats and alley cottages that could easily support three or four households on one 30-foot lot. Although the Walker’s Point neighborhood is a Latino stronghold today, it was largely working-class white during the freeway era, and the blocks south of Greenfield Avenue were predominantly Polish.

The south side’s high population density meant highly concentrated damage. In the single mile between Greenfield and Lincoln avenues, I-94 cleared a block-wide swath crammed with 411 homes and 45 businesses, many of them corner stores and saloons that had long served as centers of community. Milwaukee’s two most prominent Polish Catholic churches, St. Stanislaus and St. Josaphat, were close enough to I-94 to cast their evening shadows on the passing traffic; both parishes lost hundreds of members in a matter of weeks.

Other sections of town faced similar destruction. The never-built Park West Freeway took more than 1,500 houses on the north and west sides, leaving a scraped-bare corridor that redeveloped at a snail’s pace. And pity poor West Milwaukee. The industrial suburb lost hundreds of homes to the never-completed Stadium South Freeway in the 1960s, precipitating a steep drop in population and a sharp rise in property taxes.

There were metropolitan-scale losses, too, including landmarks such as the Layton School of Art, Cutler-Hammer’s headquarters, Socialist citadel Brisbane Hall, and a distinguished collection of churches, including Blessed Virgin of Pompeii, the spiritual anchor of the Third Ward Sicilian community.

But the greatest damage was to the people of Milwaukee. Between 1959 and 1971, the system’s busiest building years, Milwaukee County expressways wiped out 6,334 homes and displaced roughly 21,500 residents — more than the present population of Cudahy.

A form of civic suicide for Milwaukee

At the dawn of the freeway era, planners promised that “all residents will be able to ride quickly and comfortably between home and place of work, business, shops and recreation facilities.” That promise was largely kept, but it had a dark side. The freeway juggernaut was eventually recognized as a form of civic suicide, destroying tax base, accelerating suburban flight, stressing families, disrupting community life, and creating both air and noise pollution.

Racist planning decisions are certainly on the list of missteps in Milwaukee. But we should resist the temptation to make them the whole story. I recently heard a lecture by an expert on Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect whose firm designed Lake, Riverside, and Washington parks. In an otherwise erudite presentation, she criticized the Stadium North Freeway as a blight that “cut through the Black neighborhood in Washington Park, stifling economic development for decades.” The truth is that the neighborhood bordering the freeway, Washington Heights, was almost exclusively white when the bulldozers came through in the late 1950s, and it was the park itself, not the residential area, that bore the brunt of their destruction.

Revisionist history serves no one’s interest. I believe it’s possible to recognize the disproportionate damage done to communities of color, on multiple levels, without rewriting the past or losing sight of the larger picture.

I use Milwaukee’s freeways, often on a daily basis, but I’m keenly aware of their social cost. The next time you hop on one of our interstates, enjoy the once-revolutionary experience of speeding through the heart of town, but think, too, of what was taken — from all of us.

John Gurda writes a column on local history for the Ideas Lab on the first Sunday of every month. Email: mail@johngurda.com

Our subscribers make this reporting possible. Please consider supporting local journalism by subscribing to the Journal Sentinel at jsonline.com/deal.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Racist freeway planning led to damage from Milwaukee's freeway system