Rafe's battle ends: How one man's ordeal in RI's mental health system led to suicide

MIDDLETOWN — A breeze blew and the sun shone on this recent day when Judy Sweeney and her daughter, Kara Sweeney Guerriero, visited Catholic St. Columba Cemetery, situated on a rise overlooking Narragansett Bay.

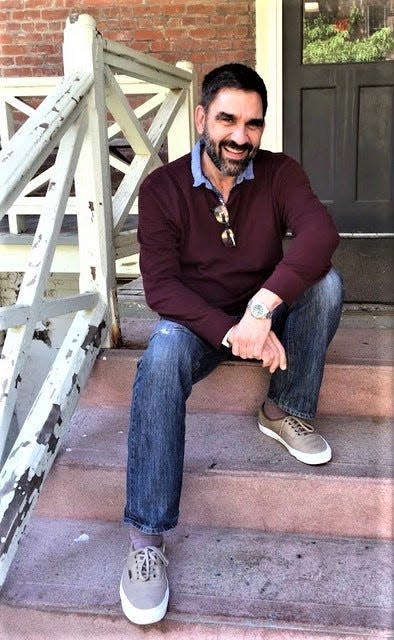

They had traveled here — Judy from her home in South County, Kara from hers in North Carolina — to pay their respects to Raphael Sweeney, Judy’s son and Kara’s brother.On May 13, Rafe, 54, ended his life by suicide.

His death followed years of treatment and hospitalizations for his mental illness, and it came not long after Easter, when, finally living outside institutional confines, he and his family had celebrated a new beginning with a home-cooked meal.

As they stood by his grave that day at St. Columba and, later, sat in the cemetery chapel, his mother and sister shared memories of Rafe, as he was known. They discussed how Rhode Island’s system of care for some of the state’s most marginalized people had failed him, like many others. They expressed hope that Rafe’s story will help bring long-overdue reform.

Rafe's story 'is not unique': Lost in RI's broken mental health system

'Hiding in Plain Sight': Portsmouth teen appears in Ken Burns' latest documentary, about youth mental health

And they spoke of his faith. In his final note, Rafe wrote that he believed he was "going home," at the invitation of Jesus.

“Rafe felt, I'm sure, that ending his life was the end of this life on Earth but that he was starting a new life in heaven, that Jesus would meet him after he died,” Judy said. “And I believe that he truly believed that — and that gave him a great amount of comfort and delight to think that's where he was going. I'm sad. The family’s sad. I'll miss him, I can't tell you how much. But I do believe that he knew he was going to be with God, and that's what he wanted.”

Her son, Judy said, was unusually compassionate.

Redemption: The fall and rise of Mark Gonsalves, who survived jump from Pell Bridge

“Rafe was such a kind and generous man. He had so many friends that he helped do things for. He could always make time for other people. He had very clear thoughts about what was right, how to live, and how to treat other people.”

“And what was important,” Kara said.

“And what was important in life,” Judy said. “It was very different than a lot of what we see in general. He didn't care about material things. He cared about people and their feelings and their needs. I think he had a great impact on the people that he met. And I think it's a wonderful legacy that he's left.”

Rhode Island children in crisis: Why doctors have declared a mental health emergency

She couldn't stop one man's jump: Now she's fighting to add suicide barriers to RI bridges

A young man gets a difficult diagnosis

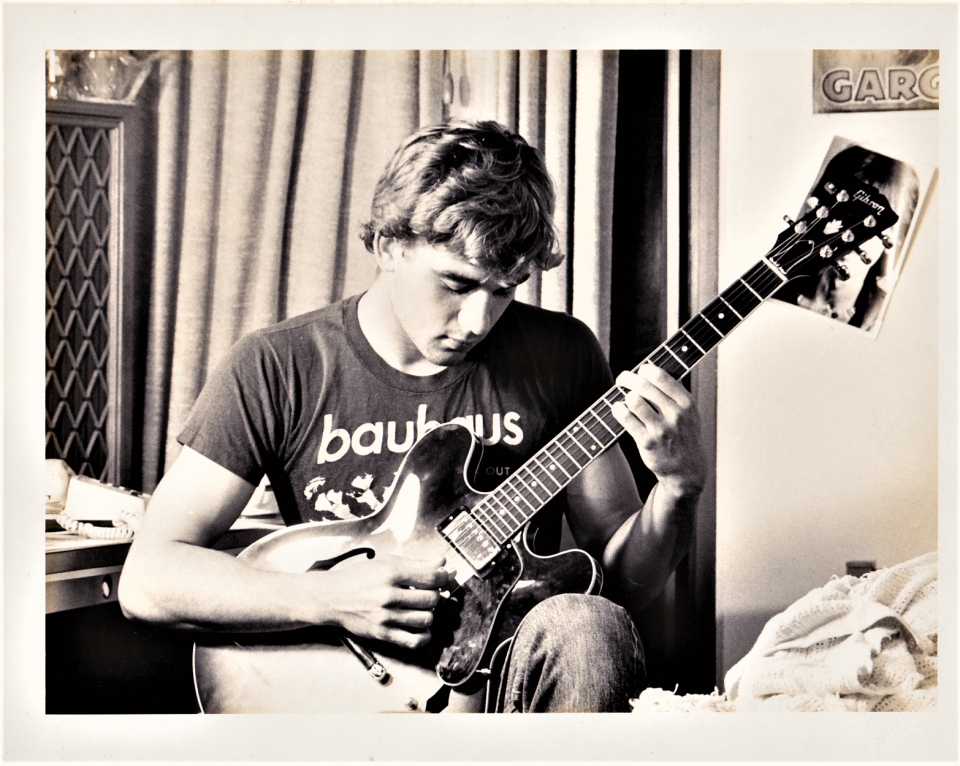

Raphael Leon Sweeney was a student at the University of California San Diego in the 1980s when symptoms of what would later be diagnosed as bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder began to surface. An accomplished guitarist who laughed easily and had a large circle of friends, Rafe managed to graduate with a degree in philosophy, but his illness was gaining ground.

After Rafe went through a series of hospitalizations and suicide attempts on the West Coast, Judy brought her son home to Newport, where she was living. With support from a community mental health center, Rafe was able to live independently and hold a job. Rhode Island in the 1990s had what was often described as a national model of community care — but by the dawn of the new millennium, the system was faltering, and Rafe was among those who would pay the price.

More: COVID is taking a toll on RI kids' mental health. How you can help

Starting a decade ago, Rafe began to cycle through several hospitals in the state. He frequently visited emergency rooms and attempted suicide on more than one occasion. In 2016, under circumstances his family says have never been adequately explained, he blinded himself while a patient at Butler Hospital. He spent time at an assisted-living center, then became a hospital inpatient.

From that time until his release earlier this year, he never left a hospital. His last stay was at Our Lady of Fatima Hospital in North Providence, where he was admitted in October 2019. He was a patient in a long-term psychiatric unit funded by the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals, BHDDH.

While there, Kara said, her brother was not allowed outside to breathe fresh air. Psychiatric care was inadequate, she said, and staff was not equipped to provide the additional services a person without sight needs. Visitation restrictions imposed by the COVID pandemic deepened Rafe's isolation.

A spokesman for Fatima could not comment, citing the federal HIPAA Privacy Rule.

What is the Olmstead Act?

“You shouldn't have to live in a hospital because you have a serious mental illness,” Kara said. “The industry standard is so far beyond that [regarding] humane treatment of people with illnesses. They should be able to get the support and services they need in an environment that's friendly, that’s in the community, where they can get out and do things …

“Nobody should be stuck at Fatima or at [state-run] Eleanor Slater, and there are people who've been there for years, decades. That's illegal if you look at the Olmstead Act, but it's also just completely inhumane, and that Rhode Island's managed to not fix this problem before now is not good.”

The so-called Olmstead Act is the name often given to a landmark 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision. According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, “the Court held that states are required to provide community-based services for people with disabilities who would otherwise be entitled to institutional services when:

“(a) such placement is appropriate; (b) the affected person does not oppose such treatment; and (c) the placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the state and the needs of other individuals with disabilities.”

Cooking dinner for himself for the first time in years

Kara, president of the firm INCITE Consulting Solutions, a health care company headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, said that while Rafe was at Fatima, she worked with BHDDH, which operates Slater and oversees non-hospital programs, to find a community placement in Rhode Island for her brother.

One eventually was found, Kara said, but it was determined it would not be able to provide Rafe with all of the services he needed. So Kara turned to a North Carolina friend: Dr. Peggy Terhune, CEO of Monarch, a company that “provides innovative support to thousands of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, mental illness and substance use disorders in North Carolina,” according to its website. Kara sits on the Monarch board.

Speaking with Terhune, Kara recalled, “in a moment of frustration, I said, ‘Could we bring him here to North Carolina?’”

Terhune was able to find an apartment, with staff, in Albemarle, some 40 miles east of Charlotte.

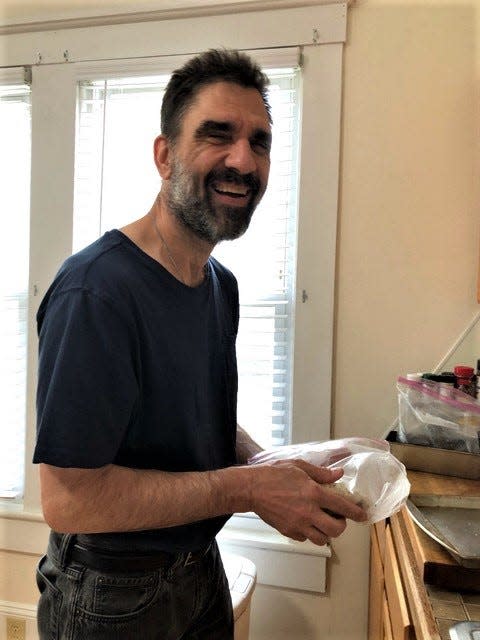

With the help of his mother, father, stepmother, Kara and her two sisters, and friends, Rafe moved in on April 4.

“The last few weeks when he was in North Carolina, he had so many good days,” his mother recalled. “He loved to play the guitar. He loved to meet new people. One of the first things he did when he got to his apartment — and he was blind and had minimal training in blind skills, even though he'd been blind for five years — was cook dinner for himself …

“What he liked to do was have me read cookbooks to him, and we did that even before he left the hospital. He took a lot of joy in shopping and making some meals and having his own independence and setting his own time schedule. One of his helpers in North Carolina took him to a softball game. And he loved meeting the people …

“He had a lot of good times in the last few weeks that he was there. He enjoyed life, and he gave a lot to people, and I'm really glad for that. It was a joy to see him smile and really be happy.”

A joyful Easter with his family

April 17, Easter, was one of those good times.

"He came over my house for Easter, mom and he," Kara said. "All of my husband's family was here, and we just had such a nice time. All the grandkids weren't scared of him being blind. They just had a great time."

Kara begins to cry.

"We had a great Easter, and he said at the table that he really just loved being part of the family again. That's what he always wanted to do, was for us to spend more time together as a family."

Last words: ‘Please understand’

On May 13, Rafe ended his life.

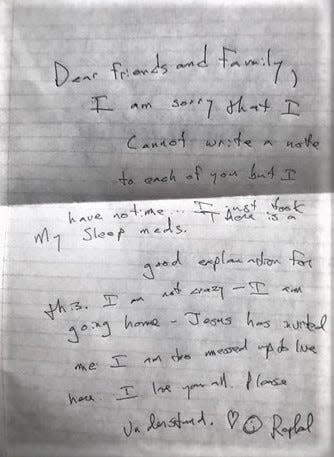

In his final note, addressed to his "Dear friends and Family," he wrote:

“I am sorry that I cannot write a note to each of you but I have no time ... I just took My Sleep meds. There is an explanation for this. I am not crazy — I am going home — Jesus has invited me. I am too messed up to live here. I love you all. Please understand. [heart] [smiley face] — Raphael”

‘A humanitarian crisis’ in mental health care

Rafe’s story is emblematic of an intensifying disaster in treatment of some of the state’s most vulnerable people, asserts Megan N. Clingham, director of the Office of Mental Health Advocate.

“Our system of care for individuals living with serious mental illness in Rhode Island is on the verge of collapse,” Clingham told The Providence Journal in an email. “It is not hyperbole to state that we are in the midst of a humanitarian crisis. People are suffering and dying due to lack of available and appropriate levels of care both in the community and in institutional settings.

“People who could live in the community are stuck in institutional settings due to lack of intensive treatment programs in the community. People who need immediate acute treatment and stabilization in an institutional setting such as community hospitals or longer stabilization at Eleanor Slater Hospital are unable to access the beds and treatment needed to progress in their recovery.”

Said Laurie-Marie Pisciotta, executive director of the Mental Health Association of Rhode Island: “Mental illness can be fatal. It can strike any one of us at any time in our lives. Given this, one would expect the state to prioritize funding for the full continuum of care.

“Yet, Rhode Island has neglected our system for decades. People with serious persistent mental illness languish on waitlists for supportive housing and services. Some live in hospitals, even when they don't need to, because there's no other place for them. Others become homeless and incarcerated. We deserve leaders who take mental health seriously. One day, it could be their son, daughter, father or mother who needs help."

“Plain and simple, Rhode Island’s mental health system is broken,” Sen. Lou DiPalma wrote in an email. “In fact, our overall state’s health and human services systems of care are in urgent need of overhaul and leadership. We in Rhode Island are unable to provide the urgently needed services in the community, in congregate care settings, including hospitals, and for individuals to remain at home, et cetera.”

DiPalma is among the legislators and advocates who for years have sounded an alarm about the deterioration of Rhode Island’s mental health system. They trace the cause to, among other factors, a combination of budget cuts, changes in leadership at BHDDH, lack of interest by other legislators and some governors, and what may be described as shifts in attitude among some voters and taxpayers who once supported a robust community system but no longer care.

“There is some solace with the recent passing of the FY’23 state budget, which includes much-needed targeted short-term and long-term investments," DiPalma wrote. "But we have a long way to go.”

Said Clingham: “This is the worst I have ever seen the system of care and safety net for our most vulnerable brothers and sisters in the almost three decades I have been doing this work. Clients, family members and treatment providers I interact with on a daily basis are beyond frustrated at the lack of investment into this system of care, without which investment things will continue to deteriorate, and people will continue to suffer and die.”

A life with meaning, ended too soon

Kara slept on a couch in her brother's apartment on his last night. The next morning, she said, "When I woke up, I thought, 'I need to get up' because I hadn't heard him get up and go take a shower to go to Mass."

Quietly, Rafe had gone.

The death of her brother solidified Kara's intention to work to improve the community mental health system in Rhode Island. Part of that involves discussions with BHDDH to bring "Monarch to Rhode Island to fill a hole in this continuum of care related to long-term services and supports and residential programs," Kara said.

"Because for some reason in the last 20 years, no one in the state of Rhode Island has been able to come up with anything creatively to be able to support people who are in these kinds of situations, either coming out of long-term hospitalizations or continuously going in and out."

As emergency personnel were about to take her brother's body away, Kara said she "told them I wanted to spend some time with him. And they finally let me.

"I told him that his life had given mine meaning, and it will continue, because people with mental illness deserve to be treated like people — having respect and giving them dignity and allowing them to have whatever kind of a life they can. Nobody should be locked up like that for so long. That damaged him as much as his actual illness."

Suicide-prevention resources: Where to turn if you are considering suicide

Anyone in immediate danger should call 911.

Other resources:

BHLink: For confidential support and to get connected to care, call (401) 414-LINK (5465) or visit the BHLink 24-hour/7-day triage center at 975 Waterman Ave., East Providence. Website: bhlink.orgThe Samaritans of Rhode Island: (401) 272-4044 or (800) 365-4044. Website: samaritansri.orgThe National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: (800) 273-TALK, or (800) 273-8255The Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741 “from anywhere in the USA, anytime, about any type of crisis.”Butler Hospital Behavioral Health Services Call Center: Available 24/7 “to guide individuals seeking advice for themselves or others regarding suicide prevention.” (844) 401-0111Thrive Behavioral Health's Emergency Services: 24-hour crisis hotline (401) 738-4300.

Prevent Suicide in Rhode Island: a Rhode Island Department of Health resource. If you are in crisis, call (800) 273-8255 or text TALK to 741741. Website: preventsuicideri.org/

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Family hopes Rafe's story of suicide will prompt reform in RI care