How to Raise an Activist, According to the Harris Women

For three generations, the Harris women have gone into the same business—social change.

The daughters of cancer researcher and civil rights activist Shyamala Gopalan Harris, Kamala and Maya Harris both entered careers in public service—Kamala was of course elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016 and Maya, who served as chairwoman on her sister’s presidential campaign, is a public policy advocate and attorney.

With their example, Maya’s daughter, Meena Harris, picked up on the family trade as a kid. She went to law school, worked in tech, and founded Phenomenal Woman—a female-powered organization that aims to raise awareness about social causes.

To hear the three tell it, activism isn’t a once-in-a-while good deed. It’s a practice and an expectation. Now with daughters of her own, Meena set out to immortalize the lessons she learned from her grandmother, mother, and aunt in her first children’s book.

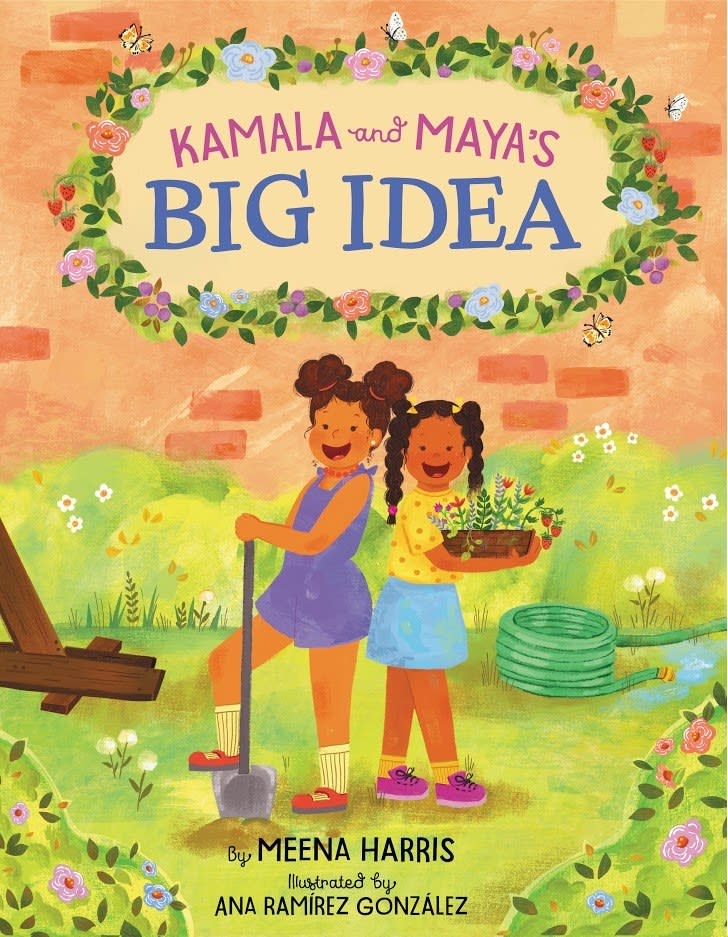

The book—Kamala and Maya’s Big Idea—is a two-birds-one-stone effort. It both makes the values Meena grew up with accessible to the widest possible audience, and it works to correct a stark imbalance. Just 7% of children’s books published in 2017 were written by black, Latinx, or Native American authors. Stories about girls of color are still underrepresented on bookshelves. Kamala and Maya’s Big Idea sets out—in true Harris women fashion—to do its part to fix that.

Available for preorder now and on sale in June 2020, the book tells the true tale of how sisters Maya and Kamala turned an unused lot in their apartment building into an area for kids. At its core, the book poses a simple but profound question: How do we raise activist girls? In an interview with Glamour, the three Harris women attempt to answer that—and reflect on their unique shared inheritance.

Glamour: Meena, how did you decide to work on this?

Meena Harris: I grew up surrounded by these strong, brilliant women who showed me what it meant to show up in the world with purpose and intention. My grandma was a single mom, my mom was a single mom, and then Kamala didn’t have kids of her own when I was young. I just idolized them—these incredible women who were all around me. Seeing [them] and hearing [their] stories was formative for me.

Once I became a mom and we started looking through children’s literature for our girls, I felt it was great that in the last three to five years there’s been this burst of literature around historical women. You have Rebel Girls—there’s a ton of that. I think that’s super important, but I also had this feeling like, Well, wouldn’t it be great if we had actual stories and real character development around girls—girls that look like mine, that were black and brown children?

Maya, how did you react when Meena told you she wanted to do this?

Maya Harris: As with whatever Meena does, the overwhelming feeling was pride. But at the same time, the activism that I think Meena captured in the book and in the work that she does was not just encouraged when I was growing up; it was expected. It was just how we were raised.

My mother didn’t have a lot of patience for whining or “woe is me.” If you saw something or you experienced something that you objected to, her response to us was not just to be mad about it or to complain about it, but to do something about it. We were always taught to stand up for ourselves, to stand up for others, to speak up.

So when Meena wanted to do this book, the first reaction I had was, “Well, what’s so special about that?” But then, even as Meena talks about it now and as I’ve had a chance to reflect, I do realize that we were blessed to be raised in a household where that was just a part of what we understood. My sister and I have talked about this a lot—our mother instilled in us the idea that to whom much is given, much is expected. She would tell us that, “You may be the first to do many things, but make sure you’re not the last.”

Kamala Harris: It was normal to us to grow up in that environment—absolutely. But as you grow up, you do realize that it’s unique. We had a very rich, nurturing childhood. It was a real blessing, and I know that now. It’s one of the reasons that of the various priorities I’ve had throughout my career, one of the greatest has been a focus on children.

We were raised in a community where the children of the community were the children of the community; there was a great sense of collective responsibility. I think one of the things that Meena does so well in the book is that she emphasizes the importance of participating in community, showing that each one, pull one. Each one has a part. It’s about the community.

Meena: I imagine that Grandma was very intentional in creating that environment, right? That she, as a mother, was thinking, “How do I raise my girls in this environment?” Do you have any sense of that now—of how she thought about it in the context of parenting? Or do you think that for her, it was just sort of all she knew?

Maya: She was very intentional about that. Some of it came through in things she explicitly said to us, right? Like what I was just talking about: To whom much is given, much is expected. To be the first, not the last. She was deliberate, and I know this may seem cliché, but she was deliberate about teaching us that we could be anything, that we could do anything. And we were really made to believe that.

So what is that about? That’s about power, and understanding your power. It’s about agency and a belief in yourself, or what you can bring forth in the world. It’s about claiming your voice and your space.

But the other thing about her is that she was not just about talk, she was also about action. And so we learned a lot by example. The adults who were around us growing up—they were all activists. Meena knows this, but our parents and their friends were active in the civil rights movement. When we were little kids, our mom would take us to meetings that she’d go to.

So it is partly, importantly, about the lessons you learn through reading, through listening, through talking, but it’s also about action. I think that those two things together form a powerful foundation for you to find your own place in the world and your own path and your own sense of commitment and responsibility and how you are going to make your contribution. I think I certainly tried to instill that for you too, Meena. And I don’t know; I think some of it’s rubbed off.

It seems like it’s working.

Maya: Yeah. It did turn out pretty good! As a single mom, I took Meena with me everywhere—rallies, meetings, class. It’s that combination of the lessons you teach through your words and what you are exposed through in terms of action. And I think both of those things are important.

The other thing is when we talk about your grandmother, I think it’s important that she never underestimated the capacity of children to listen, to learn, to understand the things that were happening around them. I feel like we grew up in a household and in a community where things weren’t “dumbed down” for the kid. You know what I mean? We got to sit at the big table, if you will. We were invited to the big table.

And I feel like you had that experience too, Meena. Sitting at the big table and asking questions. I felt absolutely I wanted to raise my daughter like I was raised, which was to be curious, to be inquisitive, to understand, to learn. I feel like you do that with [your daughters] too, which is why they are so not just loving but full of personality and curious and smart. It’s about how you are engaging them and what you’re exposing them to.

Meena: I always felt like I could participate at the adult table, but I also knew that if you’re going to make an argument about something, you better have something good to say.

Maya: That’s very much how my mom was, and I think Meena would probably attest that’s how I was as a mom too, and still am. My mom didn’t have a lot of patience for mediocrity. If you were going to actually be in the conversation and state a point of view, then you ought to be able to either explain that point of view or defend that point of view. It’s good to be challenged, to be challenged to engage and to experiment. To put out your own views and your own thinking and to have the courage to do that.

Kamala: Oh, yes. You were expected to speak and to defend your positions, no matter your age. You were encouraged to speak, but you would also be challenged. Nobody looked at you and said, “Isn’t that cute.” They looked at you as a serious human being, and they’d say, “Okay, tell us exactly what you mean by that.”

Which is…how you all became lawyers!

Meena: [Laughs.] But that’s the thing—I really want to talk to adults about this book. Because it’s not just about reading books, it’s also about action and what you’re demonstrating as a parent. I think about the fact that all these issues of inequality and the diminishing of girls and women—it starts early, right? This literally starts on the playground.

And so one of the reasons I wrote the book is if you only start talking pay inequity when women are in the workplace, it’s almost too late, right? We really need to be having this conversation with adults, because these aren’t just kids’ issues. I think it’s so important for parents to start that conversation now.

Maya: This book is focused on children, but I think that the overarching message is relevant to people of all ages. I can’t tell you how many young adults, how many grown adults have asked me over time, whether it was when I was an advocate or in politics, “What can I do? How can I help?” People are so busy with their daily lives, they’re often just trying to make it—going to work, taking kids to school, doing child care. The notion of activism or taking action is just something that’s foreign, and it seems specialized and unfamiliar and big.

So part of our work is helping people—in this case children and parents—to see and own their own power and see that change is within their reach because every one of us has a contribution we can make. I told people so often in this presidential campaign, “It will make a difference.” The smallest things add up. Meena’s book is about kids doing that, but I think that that lesson is not just for kids.

As dark as this moment is, you all seem to find a lot of joy in this work. How do you maintain that?

Meena: Oh, God, my Twitter feed is not so optimistic. But I do like to find humor in these sometimes challenging times. I think about the notion of progress; sometimes it does feel like two steps forward, one step back. And that just means you can’t get complacent. This is an ongoing pursuit, right? And I think that’s something that my grandmother definitely taught us—that this work doesn’t end. And not to be cliché, but there’s that Coretta Scott King quote: “Struggle is a never-ending progress. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” You can’t just do something and then go back to regular life. We have a lot to offer, and it’s about fighting for that.

Maya: You have to maintain some sense of optimism and hope and belief to be able just to do the work, because it’s tough. You make progress, and you have setbacks. We are going through a period of extreme setback. And you have to be able to summon within yourself a kind of courage, a strength, and a belief that change is possible. I have seen in my own lifetime that change is possible, but it doesn’t happen on its own.

For me and my sister, as little black girls and later black women growing up in America, we knew we didn’t have the luxury of complaining. My mother made that clear to us. Life is hard, and get over it because hard as you may think you have it, somebody else has it worse. You need to get up, and you need to do something for yourself, for your family, for your community, for the betterment of society.

Meena: Having had the experience of going through this presidential campaign, one of the things that was so inspiring and emotional for me was those images of little girls looking at you, Auntie, and seeing themselves in you. Kids deserve to be taken seriously. It’s just as important to talk to them about women’s equality, about fairness. We really have to focus on children early.

Kamala: Here’s the thing: When we look at children and in particular those that must be seen and heard, it is important to have role models. It is important for us to tell them that they can be anything and do anything and that we will applaud them. It is important for them to know that they aren’t alone. That’s one of the things that in terms of my childhood and the way we were raised—we were always made aware that if we ever walk into a room and we’re the only ones who look like us, we are not alone. There are a lot of us. Those that may not be present in the room are still with us, cheering us on and expecting us to use our voice to speak.

There’s so much about success that is a function of confidence, and so it’s so important that confidence at the earliest stages of life be cultivated. Meaning, the world or the people around you encourage you to be confident; they remind you that you can be and do anything. They remind you that you are special and gifted in so many ways. It’s a real blessing, and some kids get that from the family that raises them, some get it from a teacher. It could be a neighbor. It could be a faith leader. When we as a society encourage our children to soar, to run, to sing and draw and be and speak, so many good things come out of that that benefit all of us.

These interviews were edited and condensed.

Mattie Kahn is Glamour’s culture director.

Originally Appeared on Glamour