Ramón Ortíz, one of Mesilla's first settlers, a 'priest and patriot'

In the NMSU Library Archives and Special Collections, a folder of documents in the Freudenthal family papers shines a light on the early settlement of Mesilla. The documents, original land deeds to some of Mesilla’s first settlers, were written and signed by Father Ramón Ortíz during the tumultuous times following the Mexican American War. Ortíz is one of our region’s most important, and forgotten, historical figures.

In 1935, Fidelia Miller Puckett, of El Paso, Texas, wrote a short biographic sketch titled Ramón Ortíz, Priest and Patriot. The title sums up the two salient aspects of Ortíz's life. Born to a prominent New Mexican family in Santa Fe in 1814, Jose Ramón Ortíz y Mier seemed destined for a life as a soldier or government official like his father, Don Antonio Ortíz, and his brother-in-law, Lt. Col. José Antonio Vizcarra, who became governor of New Mexico in 1823. However, Ramón’s mother had other plans. She desired a life in the priesthood for her son, and her wishes won out. In 1829, at the age of 15, Ramón came under the tutelage of the priest Juan Rafael Rascón in Santa Fe and in 1833 he followed Rascón to Durango, Mexico, where he entered the seminary. He was ordained in 1837 and named cura, or priest, of the church of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Paso del Norte, current day Ciudad Juárez.

This isn’t the place to try to recount the full biography of Ramón Ortíz. There are some good published accounts of his life — such as Puckett's article as well as Mesilla historian Mary Daniels Taylor, who studied Ortíz’s life extensively, tracking down unknown primary source documentation, publishing articles and devoting a couple chapters to Ortíz in her book "A Place as Wild as the West Ever Was: Mesilla, New Mexico 1848-1872." More can, and should, be written about Ortíz, a remarkable person largely responsible for the creation and settlement of Mesilla in the years following the Mexican American War.

By the time that conflict started, Ortíz already had established a reputation as a compassionate caretaker of his parishioner’s spiritual needs, as well as a passionate defender of their rights. Mary Taylor says, “He cared for them during disasters of flood, famine, cholera, and he defended them in the despair brought on by centuries of despotism in Spanish and Mexican government … He served as buffer between residents of the Pass and tyranny. Self-doubt assailed him constantly regarding his priestly vows of humility and obedience which, more often than not, conflicted with his passionate defense of justice and an eloquent spirit quick to defend his people.”

During the Mexican American War, when Col. Alexander Doniphan invaded Paso del Norte, following the Battle of Brazito, he suspected Father Ortíz of sending messages south with strategic information about the American army. When accused by Doniphan, the priest replied “that he did not call the delivering of his country from a foreign enemy, by any means whatever, treachery. He said he was the enemy of all Americans, and never could be otherwise; and that he should use every endeavor to free his country of them.” (A Campaign in New Mexico with Colonel Doniphan, by Frank S. Edwards, 92-93) Ortíz’s words apparently made a favorable impression on Doniphan, who must have been at a loss to argue with their logic. To be safe, Doniphan took him as prisoner on the march to Chihuahua.

At the war’s end in 1848, Father Ortíz was sent to Mexico City as deputy to the Mexican national congress where he was present for the creation of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the war but also ceding half of Mexico’s territory to the United States. Ortíz was said to have argued against the terms of the treaty. The new boundary line between the United States and Mexico was to be the Rio Grande up to “the point where it strikes the southern boundary of New Mexico.” A difficulty arose in agreeing upon that point. The Bartlett-Garcia Conde Compromise of 1850 placed the southern boundary of New Mexico at the latitude of the town of Doña Ana. Everything below that line, and west of the Rio Grande, remained part of the Republic of Mexico. This is where documents penned by Ramón Ortíz become important.

Ortíz was appointed by the state of Chihuahua to serve as the commissioner of emigration for those Mexicans living in New Mexico who wished to move south in order to remain in their homeland and retain their Mexican citizenship. He was given authority to create colonies in Chihuahua, typically along its border with the United States, and to distribute land, arms and agricultural seeds to the settlers. One of the colonies that Ortíz helped established was La Mesilla, on the western bank of the Rio Grande and therefore in the state of Chihuahua. He distributed land to settlers coming south from New Mexico and those coming north from the Paso del Norte area. This land distribution continued even while the legal status of Mesilla being on Mexican or American soil was debated in Washington D.C. and Mexico City. In 1853, New Mexico governor William Carr Lane pushed the question by coming to Doña Ana and issuing a proclamation claiming Mesilla for the United States and threatening a violent takeover. Father Ortíz allegedly rode to Doña Ana and threatened Carr’s personal safety if he were to invade Mesilla. The situation was soon resolved with the ratification of the Gadsden Purchase in early 1854, moving the international boundary line further south and firmly placing all of the Mesilla Valley in the United States. Many current Mesilla residents can trace their families back the original settlers brought in by Ramon Ortíz.

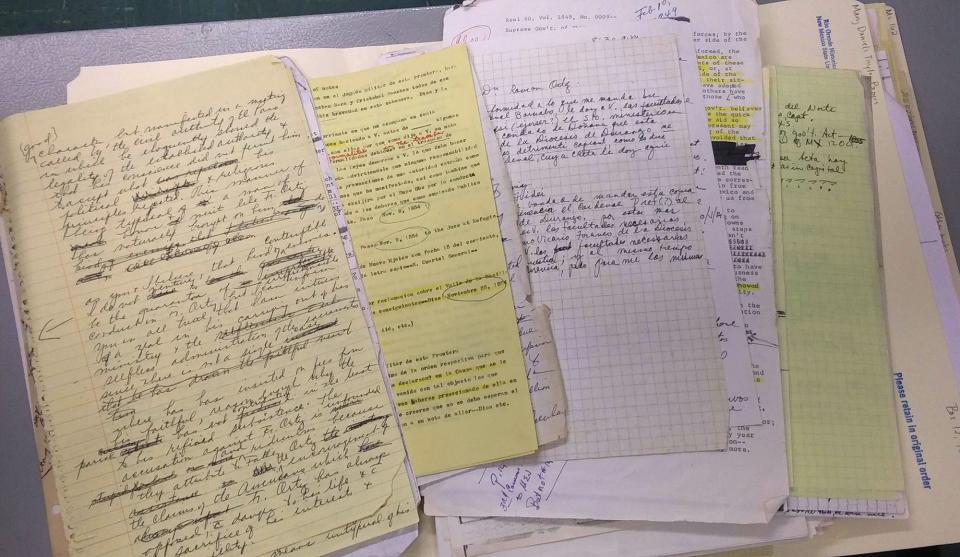

The documents in the NMSU Archives are land titles written by Father Ortíz for some of the early Mesilla settlers in 1851. The titles are in the names of Cristóbal Orozco, Jesús García and Teodoro Lucero. The documents describe the boundaries of the land granted, giving the names of the landowners on all sides, and describe how the lands will be used to build homes for their families and for the raising of crops and fruit trees. It also obligates the landowners that they will “defend the country (Mexico) from the enemies that harass them.” Aside from giving us names of some early Mesilleros, the documents allow us to see the process for establishing Mexican settlements during a most contentious time in our region. They also allow us a glimpse into the character of Father Ramón Ortíz by allowing us to read his words firsthand.

You may wonder why these documents are found in the Freudenthal family papers. The Freudenthals became large landowners in the Mesilla Valley during the late 19th and 20th centuries. These documents are accompanied by later deeds issued by the Doña Ana County Clerk’s office, and probably they describe lands in the Mesilla area subsequently owned by the Freudenthals. These original documents can be seen in the NMSU Library Archives and Special Collections. Send an email to archives@nmsu.edu to make an appointment.

More Open Stacks:

Dennis Daily is department head of Archives and Special Collections at New Mexico State University Library.

This article originally appeared on Las Cruces Sun-News: Open Stacks: Ramón Ortíz, one of Mesilla's first settlers, a 'priest and patriot'