How do you read an ancient and charred scroll? A 21-year-old college student figured it out

When Mount Vesuvius erupted, thousands of people died and a column of ash liberally covered the entire city of Pompeii and a neighboring town. The heat and debris resulted in the near-immediate carbonization of scrolls.

Though once readable, the scrolls became like blocks of rock. Contemporary archaeologists and scholars have been baffled by trying to figure out how exactly to read these scrolls to glean potentially groundbreaking information about the ancient Romans and Greeks.

It’s difficult to understate the importance of scholars figuring out how to read these charred scrolls. The Herculaneum scrolls represent “the only intact library to survive” from classical antiquity, according to The Guardian. The library itself is believed to have been owned by Julius Caesar’s father-in-law.

Related

As archaeologists scramble to reconstruct the ancient past with scant artifacts and a race against time to find more, the Herculaneum papyri have been the focal point and hope for many scholars.

And now, one University of Nebraska-Lincoln college student has managed to figure out how to read them.

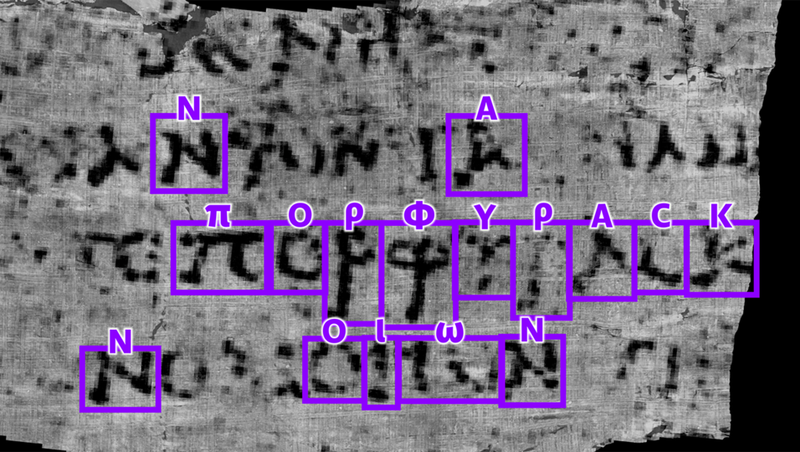

Luke Farritor used artificial intelligence (via machine learning) to read the letters on the scroll. One of the words Farritor saw was the Greek word for “purple,” per Nature. For his discovery, he was awarded $40,000 from the Vesuvius Challenge.

“This word is our first dive into an unopened ancient book, evocative of royalty, wealth, and even mockery,” longtime Herculaneum papyri researcher Brent Seales told The Guardian. “What will the context show? Pliny the Elder explores ‘purple’ in his ‘natural history’ as a production process for Tyrian purple from shellfish. The Gospel of Mark describes how Jesus was mocked as he was clothed in purple robes before crucifixion.”

Seales continued, “What this particular scroll is discussing is still unknown, but I believe it will soon be revealed. An old, new story that starts for us with ‘purple’ is an incredible place to be.”

Related

These scrolls were previously unreadable, due to their carbonization. If scholars attempted to open the scrolls, the scrolls would crumble and be lost to history.

“Until now, researchers were able to study only opened fragments. A few Latin works have been identified, but most of these contain Greek texts relating to the Epicurean school of philosophy,” Jo Marchant wrote for Nature. “There are parts of ‘On Nature,’ written by Epicurus himself, and works by a little-known philosopher named Philodemus on topics such as vices, music, rhetoric and death.”

The reading of these scrolls has been a long time coming. In the late 2010s, scholars were using a combination of artificial intelligence and X-ray technology to read the scrolls, which have an ink similar to the color carbonization, per The Guardian.

The work saw important advancements. “A new historical work by Seneca the Elder was discovered among the unidentified Herculaneum papyri only last year (2018), thus showing what uncontemplated rarities remain to be discovered there,” a 2019 article from The Guardian reported.

Brigham Young University has also been involved in the quest to read Herculaneum papyri.

“In the 1990s, Brigham Young University researchers photographed the surviving opened papyri using multispectral imaging, which deploys a range of wavelengths of light to illuminate the text,” Smithsonian Magazine reported. As time has stretched on, BYU professor Roger T. Macfarlane has been integral in making digital images of these scrolls.

So, Farritor’s advancement is one that scholars have worked for and hoped for over the course of the last few decades. If work on these charred scrolls progresses and scholars can eventually read the entirety of them, it could be one of the biggest discoveries in modern history.

Related

“Recovering such a library would transform our knowledge of the ancient world in ways we can hardly imagine,” University of Bristol papyrus expert Robert Fowler told The New York Times. “The impact could be as great as the rediscovery of manuscripts during the Renaissance.”

It’s unclear just how much of ancient literature is lost — Seales told National Geographic that it was around 95%. There aren’t clear patterns that show us what kinds of works were lost and what kinds of texts were preserved.

An advancement like this could reveal important information about the ancient world.

“A vast majority of ancient Latin and Greek texts have been lost. Sophocles wrote more than 120 plays, of which only seven have wholly survived. Just 35 books of Livy’s 142-volume history of Rome are known to exist,” Nicholas Wade wrote for The New York Times. “Almost all the poems of Sappho have vanished. Retrieving an entire classical library would vastly expand knowledge of the ancient Greek and Roman worlds.”