How a real estate developer convinced NC to build a highway on a string of islands

In 1933, Frank Stick had a vision.

Stick, a real estate developer and conservationist, wanted the federal government to create the nation’s first oceanfront national park. The South Dakota native had moved to Roanoke Island in 1929 and saw a chance for the government to use condemnations, land donations and purchases to patch together and preserve a 25-mile stretch of seashore, largely along Hatteras Island.

“This is the last great stretch of ocean frontage available on the Atlantic coast, today, and once gobbled up by speculators, our last opportunity to create a coastal park is gone forever,” Stick wrote in The Independent, a weekly newspaper out of Elizabeth City.

Stick’s essay was titled “A Coastal Park for North Carolina and the Nation” and was accompanied by a map showing the proposed Franklin D. Roosevelt Coastal Park along Hatteras Island. Soon after, the project would be renamed the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

To go with that park, Stick imagined a road running the entire length of the Outer Banks, a continuous stretch of pavement, constantly maintained to open to tourists the immense beauty and natural wonders of the then largely inaccessible barrier islands’ beaches and hunting grounds.

“This roadway is no fantastic dream; no expensively enthusiastic scheme to attract public or political favor, but a sensible, well thought out project that would prove of inestimable economic and esthetic value,” Stick wrote.

Over the course of the next half century, that road came together piece by piece. Where inlets had once kept villages isolated, bridges and ferries began to connect them while also bringing the outside world to the Outer Banks. Segments of the road were called a variety of names, including State Highway 34, State Road 1200 and State Road 1323.

In 1963, North Carolina gave the road the name it has today, a name that is nearly synonymous with travel to the Outer Banks. It can be found on a multitude of stickers and baseball caps and T-shirts: N.C. Highway 12.

The fate of Highway 12 has always been a topic of debate, particularly after storms. It was raised after the Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962, after Hurricane Irene reopened New Inlet in 2011 and after waves and storm surge from 2019’s Hurricane Dorian broke two segments of road on the northern end of Ocracoke.

Much of the damage in recent years has been concentrated in seven “hot spots,” including six on Hatteras Island and one on Ocracoke’s northern end. These are places where the shoreline is rapidly eroding or the island is particularly narrow.

In May, Bob Woodard, chairman of the Dare County Board of Commissioners, announced a task force made up of representatives from local governments, the National Park Service and the N.C. Department of Transportation. The group’s mission, Woodard said, was to find ways to address those hot spots.

“It’s time that we have a long-term plan, and that’s not in the mix right now,” Woodard said. “We’re reactive, and we need a long-term plan to resolve this.”

The beginnings of the road

Today, the northern end of N.C. 12 terminates in Corolla, on a stretch of road tucked between two developments of vacation mansions with prices in the millions of dollars. The southern end lies 148 miles away, a stone’s throw from a Dollar General in Sea Level. But once, the Outer Banks was a collection of fishing villages on small islands traversable only by dirt roads or by driving across hard-packed sand at low tide.

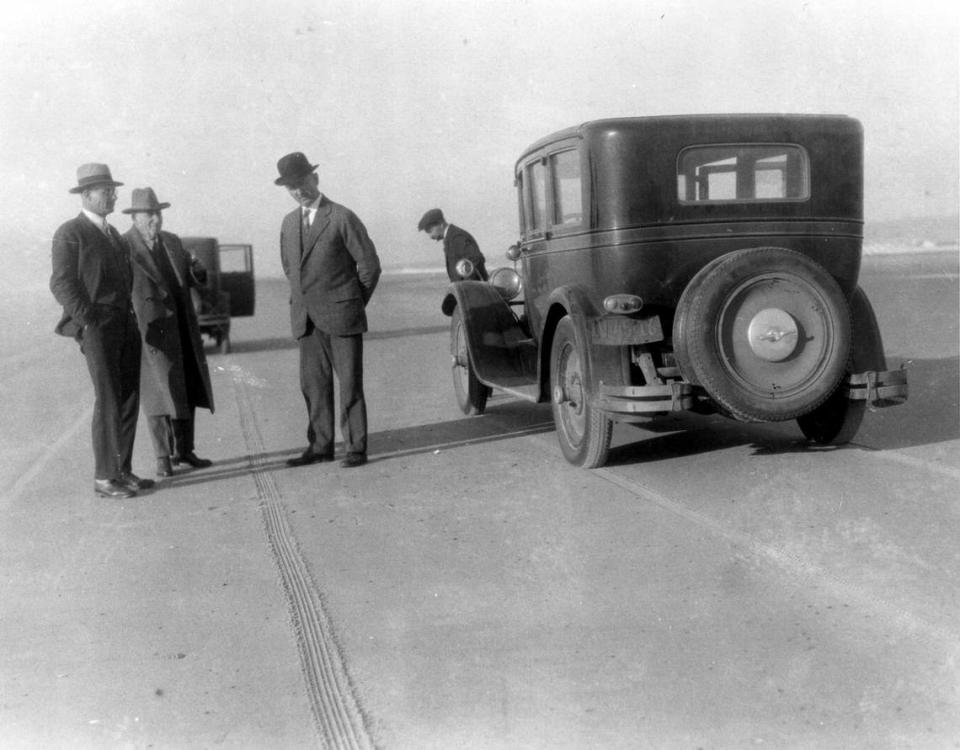

The first bridge to the Outer Banks was built in 1927, about six years before Stick wrote his editorial in the Elizabeth City paper. That $300,000 bridge ran from Manteo on Roanoke Island into Nags Head, which is about 10 miles south of Kitty Hawk. Dawson Carr, a historian, later wrote that its construction “altered life forever” on the Outer Banks.

By 1929, that bridge was followed by another, this one crossing the Currituck Sound before landing in Kitty Hawk. Dubbed the Wright Memorial Bridge, the project was funded by a group of Elizabeth City businessmen who, Carr wrote, paid for the project with the hopes that it would boost the value of large tracts of land they owned on the Outer Banks.

Then, in 1931, North Carolina paved an 18-mile stretch of road between the bridges. This was the first paved portion of the road that later became North Carolina Highway 12. A short time later, the state bought both bridges.

Even with the road paved from Kitty Hawk to Nags Head, those living in the villages on Hatteras Island to the south remained leery of Stick’s proposal for a coastal park and the associated road. Much of that skepticism was linked to one paragraph in a 1938 National Park Service document evaluating the proposed Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

“It is definitely the desire of the National Park Service that the section between Oregon Inlet and Hatteras Inlet” — all of Hatteras Island — “remain in its natural condition without any roads so that future generations may see this and other undeveloped sections as they are in our day,” National Park Service officials wrote.

In a 1940 letter to Bruce Etheridge, chairman of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Commission, Stick argued that building a road benefitted every one of the roughly 5,000 people living around Cape Hatteras at the time and actually had environmental benefits.

“Some means to facilitate transportation and to keep automobile traffic from traversing all sections of the beach is an obvious requirement if the reforestation and sand fixation program is ever to be completed,” Stick wrote. “Also, from the standpoint of wildlife conservation and natural propagation, traffic must be restricted to a certain defined area, and this cannot be accomplished without improvements in travel conditions.”

Stick won the argument and his vision came to fruition: In early 1953, the federal government officially established the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The park was dedicated five years later, during a ceremony at the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

Connecting the villages

While Stick was working to establish the seashore, Ernie Foster was growing up in Hatteras Village, on the island’s southern end.

When Foster was a child, a dirt road ran north from Hatteras Village. A bus line operated by the Midgett Brothers was the quickest way to reach Oregon Inlet. The arrival of the mail was the highlight of each day.

“Everyone came to the post office, and the contact and interaction on a daily basis at the post office was a pretty big deal,” Foster said.

Foster’s father, Ernal, founded the Albatross Fleet, the first charter fishing boats in North Carolina, based out of Hatteras. Foster maintains a pair of work sheds with different tools and caulks and a mound of fishing nets. The ceiling of one of them is lined with fishing poles that he has collected over the decades, the different colors and grips running together to form a kind of visible history of the state’s charter fishing industry.

As Foster grew older, the road grew, too. It started with a patch of pavement outside the Albatross Fleet’s headquarters in 1947. Then the road stretched north, passing through Frisco and Buxton before ending at Avon, allowing schools in the once-isolated villages to consolidate.

In fourth grade, Foster moved to the newly consolidated school.

His father and uncles warned him that he should be ready to scrap with the other children because of ongoing village rivalries. But when the kids actually got under the same roof, they got along.

“There were no problems based on, ‘You’re from Kinnakeet and you’re from Buxton, you’re from Hatteras.’ We were just kids. We saw none of that,” Foster said. In his view, the road drew the villages closer together.

Bridges back home

As a child, Foster knew that when his parents ran an errand to Manteo or Nags Head, they had to be home by nightfall because they would need to cross Oregon Inlet via ferry.

Foster took his last ferry ride across the inlet for many years in the fall of 1963, when his parents drove him to his freshman year at N.C. State University in Raleigh. On the drive home at Thanksgiving, Foster crossed the newly dedicated Bonner Bridge for the first time.

As he crested the bridge on that drive, Foster said he thought, “I was going home.”

“For the 14 winters that I spent in Raleigh,” he said, “I never came back without, once I got to the top of that bridge, rolling the window down to breathe the air. Rain, shine, sleet or snow, when I got at the top of that bridge, I was going to smell the air of the ocean and the area. Never ceased to do that.”

Protecting a vulnerable road

During a Dare County erosion control hearing at the John Yancy Motor Lodge on Feb. 15, 1964, David Stick, Frank’s son, told the crowd that the highway and homes along the Outer Banks were already imperiled by the often-angry sea. David Stick had emerged as a powerful figure in his own right, and was then serving as chairman of the Dare County Board of Realtors. He was also the first mayor of the Town of Southern Shores, which he helped develop, and served on the Dare County Board of Commissioners.

“At no point in our developed coast are we safe from the potential ravages of the sea,” Stick said on that February evening, according to his prepared remarks. Stick posed several solutions, including beach nourishment and structures like groins or jetties that could capture the ever-shifting sand.

By that point, more than 30 years of projects had been undertaken on the Outer Banks to try to defend the shoreline from erosion.

Between 1937 and 1941, about 2,500 workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration undertook the first large-scale erosion control efforts on the Outer Banks, installing 4.1 million feet of sand fences.

The lines of fences captured sand carried by the winds and currents. Over time, a small dune would form and the workers would place another layer of fences on top, according to the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Administrative History. Once the structure was intact, the workers would put grass and plants on top to help keep the dunes intact.

Still, the erosion continued in many places, with some homeowners building bulkheads to protect their property and others burying their old Christmas trees in an effort to create a dune. At the 1964 meeting, Stick, who had several years before published a book titled “Handbook for Erosion Control,” identified several potential causes of the ongoing erosion.

In addition to the barrier islands’ sand drifting south and toward the mainland, Stick said, “Throughout its history, the earth has been subjected to periods of gradual change in temperature. As the temperature fell, more and more of the water on the earth’s surface would freeze. As the temperature rose, the ice would begin to melt. We are now in a period of gradually rising temperatures, with the result that the ice cap is slowly melting and the oceans of the world are rising.”

David Stick was describing climate change, long before the term became commonplace. Stick made his observation decades before the general public came to understand that increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere would lead to global warming and cause sea levels to rise faster, increasing pressure on low-lying places like the Outer Banks. One woman, Stick said, had written to wish the committee well in its efforts, but said that retreat was inevitable.

By the early 1970s, scientific thinking on erosion control had shifted, according to the Cape Hatteras history. Biologists were starting to believe that artificial dunes and jetties could be doing more harm to the beach than good. National Park Service leaders decided the agency would stop paying to build up the dunes.

In a Sept. 28, 1973, statement justifying the decision, the National Park Service said it believed the mounds of sand could have caused or intensified a breach of Highway 12 just north of Buxton during 1962’s Ash Wednesday Storm.

Even after the Park Service’s decision, North Carolina highway officials had little choice but to continue pushing sand that blew onto or washed across the road back into the dunes, according to the seashore’s official history. The practice continues today.

With the road in place, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore emerged as a popular destination. Between 1973 and 1987, the park drew between 1.22 million and 1.8 million visitors each year, averaging about 1.57 million.

Highway 12 also continued to grow, with its latest extension completed in 1987 — about 15 miles of pavement extending north from the then-terminus at the Town of Duck.

“There used to be an old gate at the Dare-Currituck County line. That gate was torn down in 1985 and the state paved the road up to Corolla,” H.B. Briggs, then Currituck County’s chief planner, told The Washington Post in 1991.

Extending the highway opened the Currituck County Outer Banks to a swift increase in development. The Post wrote, “A good growth indicator is the number of lots created from larger parcels of property.”

In 1985, 125 lots were subdivided from Corolla to Currituck County’s southern boundary, Briggs told The Post. That spiked to 500 lots in 1988 and 430 in 1989, after the road was completed.

Ray Sturza, then Dare County’s planning director, told The Post much of the growth he saw throughout the 1980s was concentrated around Duck, as well.

Asked about the area’s draw, Sturza said “I guess it’s the remoteness of the location. Exclusivity. A sense of being away from it all.”

Replacing the Bonner Bridge

In 1990, a barge rammed into the Bonner Bridge, causing it to be closed for more than three months for repairs. A temporary ferry crossing carried vehicles across the inlet while the work was done. By 1993, efforts to replace the Bonner Bridge had begun.

Around the same time, other stretches of N.C. 12 were causing substantial headaches for the N.C. Department of Transportation. Between 1987 and 2000, the state spent nearly $32 million repairing the road, including nearly $1 million to bury large sandbags along a portion of N.C. 12 about five miles south of Oregon Inlet.

“Anytime you can ride down a highway and spit in the ocean on one side and the sound on the other, you’ve got problems,” R.V. Owens III, a onetime member of the N.C. Board of Transportation, told The News & Observer in September 2000.

By 2003, it had become clear that state and federal agencies favored a 17-mile bridge built through the Pamlico Sound. In addition to replacing the now-decrepit Bonner Bridge, the sound-side proposal would eliminate vulnerable spots just south of Oregon Inlet, at the Pea Island Visitors Center and at the “S curves” just north of Rodanthe.

Dare County residents and officials opposed the long bridge, The News & Observer reported at the time, concerned that the Pamlico Sound option would limit access to Hatteras Island north of Rodanthe, with the existing road likely being torn up or given only limited repairs.

In 2004, the state shifted gears, focusing its efforts instead on a route slightly to the west of the Bonner Bridge.

Then-Sen. Marc Basnight, one of the state’s most powerful politicians, was a staunch supporter of the shorter span. He defended the project for years, even as environmental groups and advocates expressed doubts about its viability.

Opponents of the shorter span were particularly worried about the future of Pea Island, arguing that the flood-prone northern end of Hatteras Island was narrowing over time. Maintaining a road there, they argued, would only hasten erosion and further imperil access to the Hatteras Island villages.

In a January 2010 editorial in The N&O, Basnight wrote that elevating the most vulnerable portions of Highway 12 made more sense than a long bridge into the sound, particularly if sea levels continued to rise and parts of the Outer Banks were to wash away.

“If predictions of Pea Island’s fate are correct,” Basnight wrote, “over many years this project would end up as several short bridges in the ocean, connecting small islands like the Chesapeake Bay Bridge instead of one long bridge into the sound.”

Looking to the future

The Southern Environmental Law Center, representing Defenders of Wildlife and the National Wildlife Refuge Association, ultimately filed and settled a lawsuit over the Bonner Bridge project. Per the settlement, DOT moved forward with the parallel Bonner Bridge replacement but pledged to consider options swinging into the sound around Rodanthe and New Inlet near the Pea Island Visitors Center.

Derb Carter, the director of SELC’s North Carolina offices, said of the 17-mile proposal, “It’s a bridge they’re eventually going to have anyway because the whole island is falling apart. Are you constantly going to spend millions or hundreds of millions of dollars trying to fight the ocean? Or come up with a longer term plan?”

The $252 million Bonner Bridge replacement — now named for Basnight — opened in 2019, and the first cars are set to cross the sound-side bridge near Rodanthe early next year.

Like Carter, local officials and transportation engineers have turned their eyes toward what’s coming next, with the Dare County and National Park Service-led task force meeting and a subcommittee sorting through potential solutions.

On the Outer Banks, everyone knows the next storm isn’t far off. With the task force, members said, they will be poised to rebuild better after storm surge or a new inlet breaks another vulnerable section of N.C. 12.

Bobby Outten, Dare County’s manager and one of the task force’s organizers, said, “It’s so much easier and better to do things now while you can think about it and reflect and make good decisions than trying to react while you’ve got three to four feet of water on the road.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a Southeastern U.S. Ocean and Climate reporting grant from the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources. This story was also produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work.