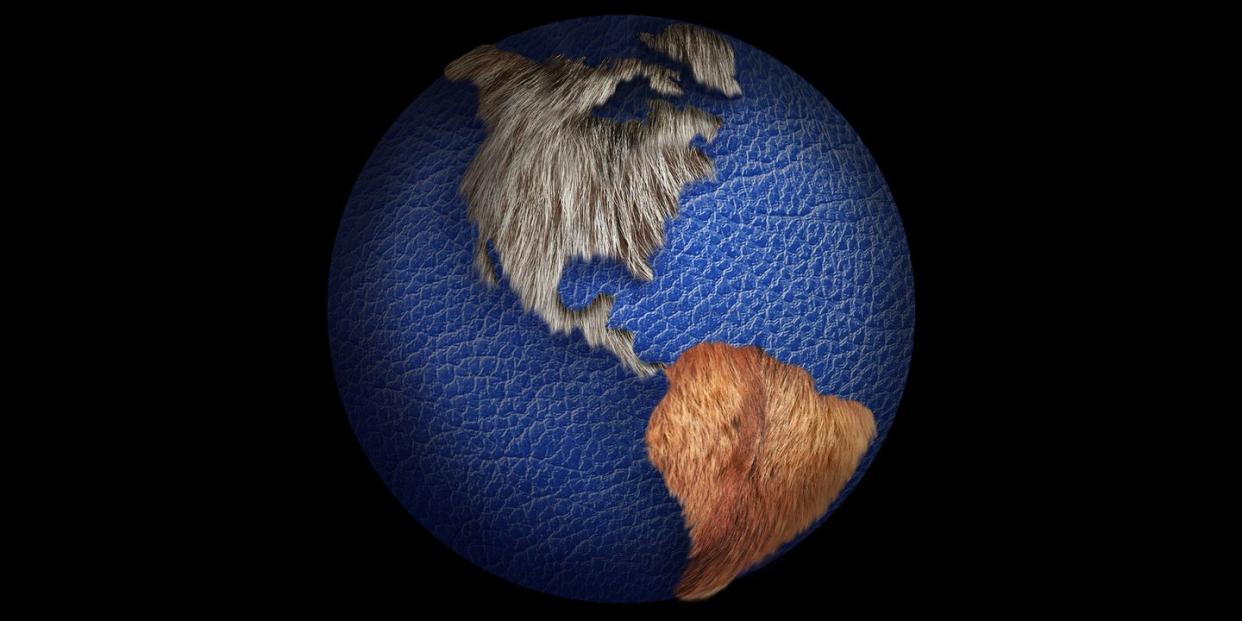

Real Fur is Bad for Animals. Fake Fur is Bad for the Earth. What the Hell Do We Do Now?

Banning animal product in clothing is complicated. Brands, fashion houses, and even cities (notably, Los Angeles and San Francisco) are taking a hard stance on eliminating the production and sale of fur, citing consumer requests, animal cruelty, and sustainability standards. Versace, Gucci, Armani, and Michael Kors have pledged to design and produce fashion without the use of some or all animal products, namely fur or leather. These big-name moves have incited big-name reactions, especially when it comes to sustainability.

On one side, organizations like PETA and the Humane Society laud these designers’ moves, noting that animals are tortured on every level of fur and leather production. Even if those animals aren’t actually killed in the name of fashion, they will almost certainly be stabbed with shears, trapped in cages, and spared only to serve humans.

On the flip side, the Fur Information Council of America (FICA) will tell you that fur is hyper-regulated-one of the “most regulated industries to exist.” (FICA cites the efficacy of state-enforced practices and its avoidance of endangered species.) It argues that faux furs are actually the greater environmental problem: The methods and materials used to manufacture faux fur are full of petrochemical poisons, which pollute the earth, the air, and the oceans, killing the very beings animal-rights groups believe they’re saving by stopping the fur trade.

There’s an implicit connotation that animal-free is more sustainable, but that’s simplistic and misleading. Some of the most harmful fabrics on the planet include denim and other cotton textiles. Denim producers dump heavy metals into bodies of water. Industrial cotton production requires a heavy diet of carcinogenic pesticides, which inevitably leach into water supplies. The line you’ve been fed about fashion houses going animal-free? It hardly explains the scope of production harm in the industry at large.

So while a headline announcing a huge fashion house is banning leather or fur might sound nice, it doesn’t have much depth beyond the ban. It doesn’t explain what the alternative fabrics will be, how the manufacturing process will change, or if the ban will have an impact on sustainability at all.

But that headline isn’t useless: It’s bringing attention to problematic clothing manufacturing processes that need a reboot. Because producing and manufacturing real fur, faux fur, and clothing in general has serious environmental repercussions. It’s time for consumers to question what their clothing is made from, how it’s made, and where it goes once it’s thrown out. It’s time for brands start answering.

Fur alternatives have existed for years, but there is still no universally accepted standard for what makes a fabric-animal or not-sustainable, eco-friendly, or, at the very least, not harmful.

Take vegan leather, for example. Brands like Banana Republic, BlankNYC, and Free People offer “vegan” leather jackets, which cost much less than a conventional leather. (They’ll run you about $50-$200, whereas real leather jackets tend to cost $500 and up.) But in this context, “vegan”-like the word “natural”-holds no true meaning. There's no third party-reviewed standard, and no official requirements of any kind.

“Vegan leather isn’t a new term; it’s been around for a long time,” says Suzanne Lee, Chief Creative Officer at Modern Meadow, a New Jersey-based company specializing in creating advanced (and heretofore unimagined) materials. “It has referred to pleather, vinyls, fabrics that came from fossil-fuel sources. But now, we’re starting to see alternatives to furs and leathers that aren’t petrochemical-based. These potentially have a better environmental footprint.”

Those alternatives include materials like Modern Meadow’s own alternative to leather: Zoa, a “bioleather” created with lab-grown collagen. As for the potential environmental footprint, it’s hard to determine what that might look like. Zoa, for example, doesn’t officially launch until later this year. In theory, it’s biodegradable. But in practice, it’s only possible to know once it exists in the mass market.

And it's worth noting that in fashion, the overall footprint of a material or item is already hard enough to define. Nearly anything in the manufacturing process can be harmful to the planet or its inhabitants, from the way cotton seeds are planted to the way leathers are tanned. A “sustainable” practice could refer to a single step of the manufacturing process, a few steps, or the entire operation.

“When you see a [USDA Certified Organic] label, you have trust that it’s organic because that label is backed by a standard,” says Michael Sadowski, a sustainability advisor to fashion brands. “There’s a lot of infrastructure behind, say, an organic banana. We don’t necessarily have that just yet in the footwear and apparel space. It’s a little too complicated.”

“Complicated” might be an understatement. Fashion, on a global scale, is complex not only because of the numerous steps in the manufacturing process, but also because that process looks different for a jacket, a shoe, or a bag. So while a top-down, systematic change in sustainable fabric production may be unrealistic in the near-term, brands and consumers can still create bottom-up solutions. That starts by being better informed. It’s up to us to take the available knowledge we have and use it to be smarter consumers.

One point of focus for brands and consumers is a life cycle assessment, Lee suggests. An LCA evaluates the environmental impact of a product by analyzing every step of a product’s life, from the initial material to what happens when the product is thrown away. (A mapping practice referred to as “cradle to grave.”)

Levi Strauss, for example, conducted a study on its denim’s life cycle. Although there is LCA software available, Levi’s instead made its own proprietary measures tailored specifically for an article of clothing. For example, the study found it takes 3,800 liters of water to make a pair of jeans, and if consumers washed their jeans every 10 wears instead of the average two, it could lessen water intake by 80 percent.

These findings led to systematic changes in Levi’s production. To address water concerns, Levi’s launched its “Water

That’s what made this study so important: It wasn’t just about how denim’s life cycle impacted the earth. It provided actionable solutions to how the brand and consumers could help reduce it, too. It also made sustainability more palatable to the fashion industry at large. By creating its own standard, Levi’s also created a template for product and manufacturing transparency.

“Do we care only that it comes from an animal or not?” says Lee. “If, instead, your motivation is to purchase products that do no harm to animals, to people, or the planet, then it starts to get way more complicated. What is it made from? How is it made? Who is it made by? What happens to it at the end of life?”

Companies committed to minimizing the environmental impact of their infrastructure should be able to answer these questions, or at least identify ways to improve.

Rather than finding a cheap, quick substitution for fur, Modern Meadow's Zoa-the biofabricated "leather"-is a completely new alternative. While the end goal is something we'd all recognize (a jacket, for instance), what it takes to get there is entirely outside of our standard processes. The brand doesn’t start with cutting fabric; it starts with cutting DNA.

The production engineers there are creating lab-grown collagen, a protein in connective tissues and organs-notably, skin-to turn into leather. Because real leather comes from animal skin, it relies on collagen for elasticity and durability. Modern Meadow’s work, then, is in engineering the proteins and connecting them in a way that replicates actual leather.

“We’re growing the building blocks of nature-collagen-using a living organism,” says Lee. “We’re bringing together chemistry and design, so we can create new types of materials that are better than they were before. It’s an interesting moment in time. We’re moving in a direction where we no longer need to go to nature to get those materials.”

Those materials, like biofabricated collagen, wouldn’t damage nature, either. Although the company's process is still in the works (and mostly private), it plans on having less water usage and CO2 emissions than real animal-based products do. It won’t take an animal’s life, and it also won’t contribute to toxic waste like faux furs do.

But while a biofabric is promising, it’s still in its nascent stages. The only public-facing product from the company so far was in the MoMA's Items: Is Fashion Modern? exhibit in 2017. Still, Zoa is working with brands (all of which are under wraps) to launch product this year. Pricing also isn’t available yet, but once Zoa products are available to purchase, there will be a clearer indication of how long it’ll take to phase the material into the mainstream.

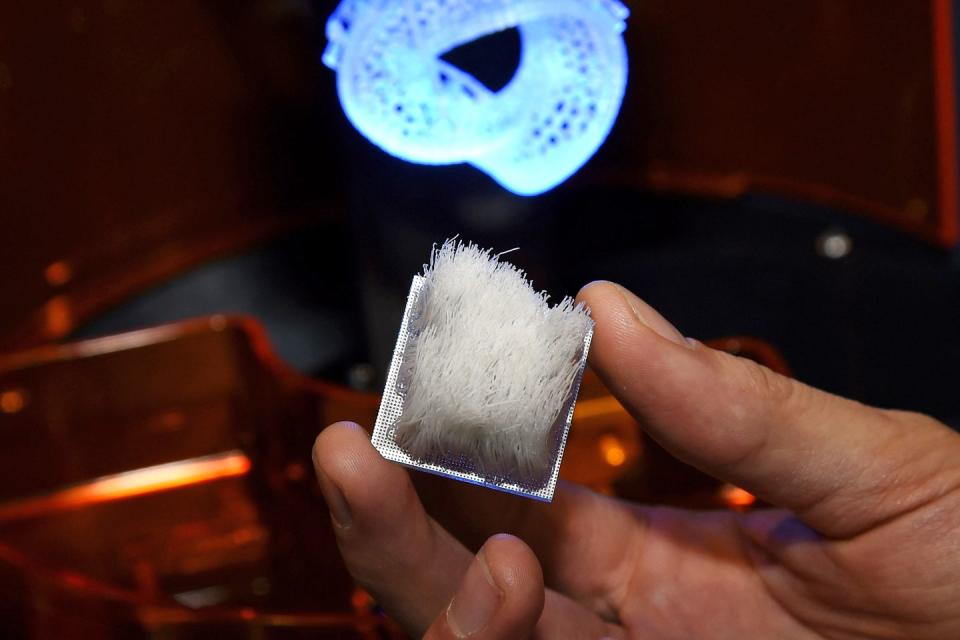

There’s also another type of process trying its hand at replicating nature: 3D printing. At MIT, researchers are developing 3D-printed hair, which could theoretically recreate the exact structure of animal fur. This addresses one of the main arguments fur advocates (select designers, and those advocating for the fur trade) have provided: Fur replacements are just not the same as fur. They don’t have the same properties, or abilities, or touch. It’s like vegan cheese, they argue-it’s never going to come close to the real thing.

3D-printed “fur,” however, could change that. This process theoretically means that the print could be customized to suit all kinds of needs and uses. Potential designers could play with the length, the thickness, and the structure of each hair. This artificial product could get so close to the makeup of real animal fur that an untrained consumer might never know the difference.

“I think from more of the design perspective, it’s freeing,” says Jifei Ou, the lead researcher on 3D-printed hairs research at MIT. “You can make the fur as stiff as a toothbrush or soft as silk. What do you do when you can control the fiber of each strand? It opens up design and imagination.”

3D-printed materials also address sustainability in fashion because of their inherent closed-loop life cycle. At the end of its usable life, 3D-printed hair could be melted down to create something new. It’s a contained process: The initial material is the only element that could potentially impact the environment.

“It’s complementary to real fur and faux fur,” says Ou. “For so long, real fur represented social status and presentation. This new technology actually represents a new type of luxury. How can designers and engineers come together to create a new place? It’s not here to replace fur or fake fur; it’s new.”

However, the research is just beginning. Ou notes they’re still “years” away from having a complete structure and material that could be used to design clothing and beyond. Until then, he can’t yet estimate how much a 3D-printed fur jacket would sell for.

The true impact of those brands, fashion houses, and cities banning furs and leathers is in what it means for material innovation at large. It’s a chance for both companies and consumers to reevaluate how they make, purchase, and evaluate products.

It’s not just the apparel industry that could benefit from new materials, either. 3D-printing, for example, is also in demand from medical professionals. If, in theory, one could print the hair at any length, width, or size, medical researchers could use the hairs to replicate parts of human anatomy. Specifically in demand, says Ou: the villi lining of a human’s microbiome, which would allow researchers to recreate a workable, testable environment to which there's only limited access right now.

These newer materials, should they scale effectively, would make the archaic fur-versus-faux-fur argument obsolete. Instead of doing things the way they’ve always been done, these new materials give way to more sustainable, conscious production.

“We’re in the dawn of a new materials age,” says Lee. “It brings together both the natural and the man-made world to create something more sustainable. This is just the beginning.”

('You Might Also Like',)