Real History with Jeff LaHurd: At the end of a long journey, ‘Little Scotland’ was nowhere to be found

As a young Nellie Lawrie recalled some years later, there was much apprehension and plenty of tears as the Scot Colony boarded the S.S. Furnesia at the Greenock Pier.

The group was sailing from Glasgow to New York. Then, by rail and steamboat, they would reach faraway Florida and the “Little Scotland” awaiting them in Sarasota.

Family and friends were dockside to bid them goodbye, “Auld Lang Syne” was sung, and by the time the ship sailed into the darkness, tears were streaming.

Even for 1885 it was a long voyage. The November weather was cold and stormy in the Atlantic, there was engine trouble on the steam/sail ship lengthening the time of the voyage, and seasickness was common.

When colonists finally docked, quarantine officers checked them over, looking for the mark of the smallpox vaccination before allowing them ashore.

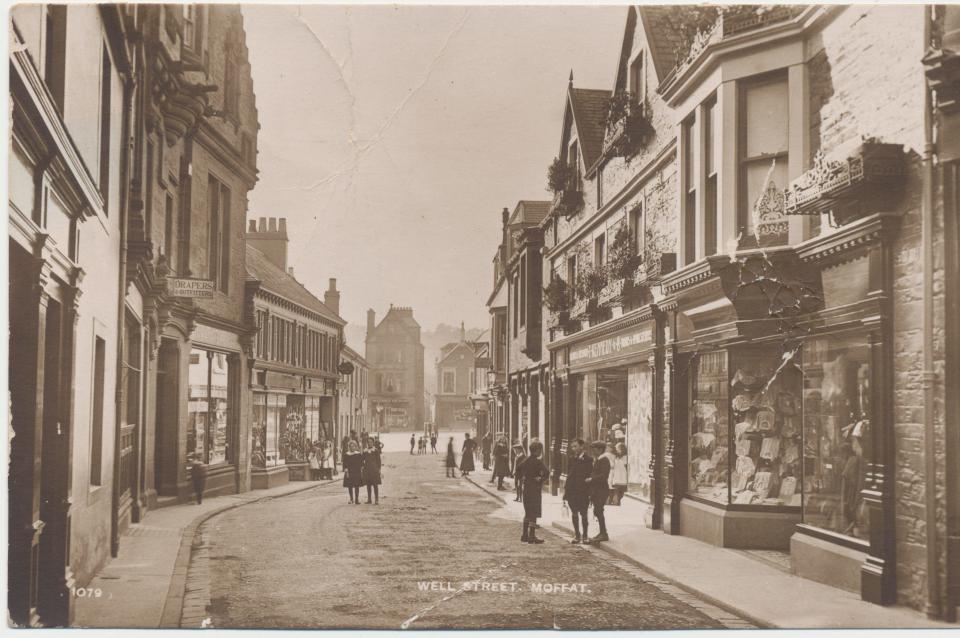

Alex Browning wrote in his memoirs that the group was met by a representative of the Florida Mortgage and Investment Company and led to the Continental Hotel across the street from the docks. Lawrie remembered it differently. According to her recollection they were left to their own devices on a late, heavily raining night. “Father and Uncle John Browning went scouting along West Street, not the best street in New York. So we entered the Metropolis of America trudging thru the rainy street carrying our baggage to a second class hotel.”

Coming from Scotland, then in an economic downturn, some from small towns, New York was an impressive sight indeed. Browning called it “the most amazing city I had ever seen. The brilliancy of the Broadway lights made Paisley seem like a deserted village.” He recalled that they walked the streets “like most exemplary hayseeds,” having a beer with a free lunch and “marveling at the generous display of food as compared with similar conditions in the Old Country while drinking their half and half.”

After the short and memorable visit, the excited colonists boarded the Mallory Line’s S.S. State of Texas for the trip to Fernandina on the Atlantic coast.

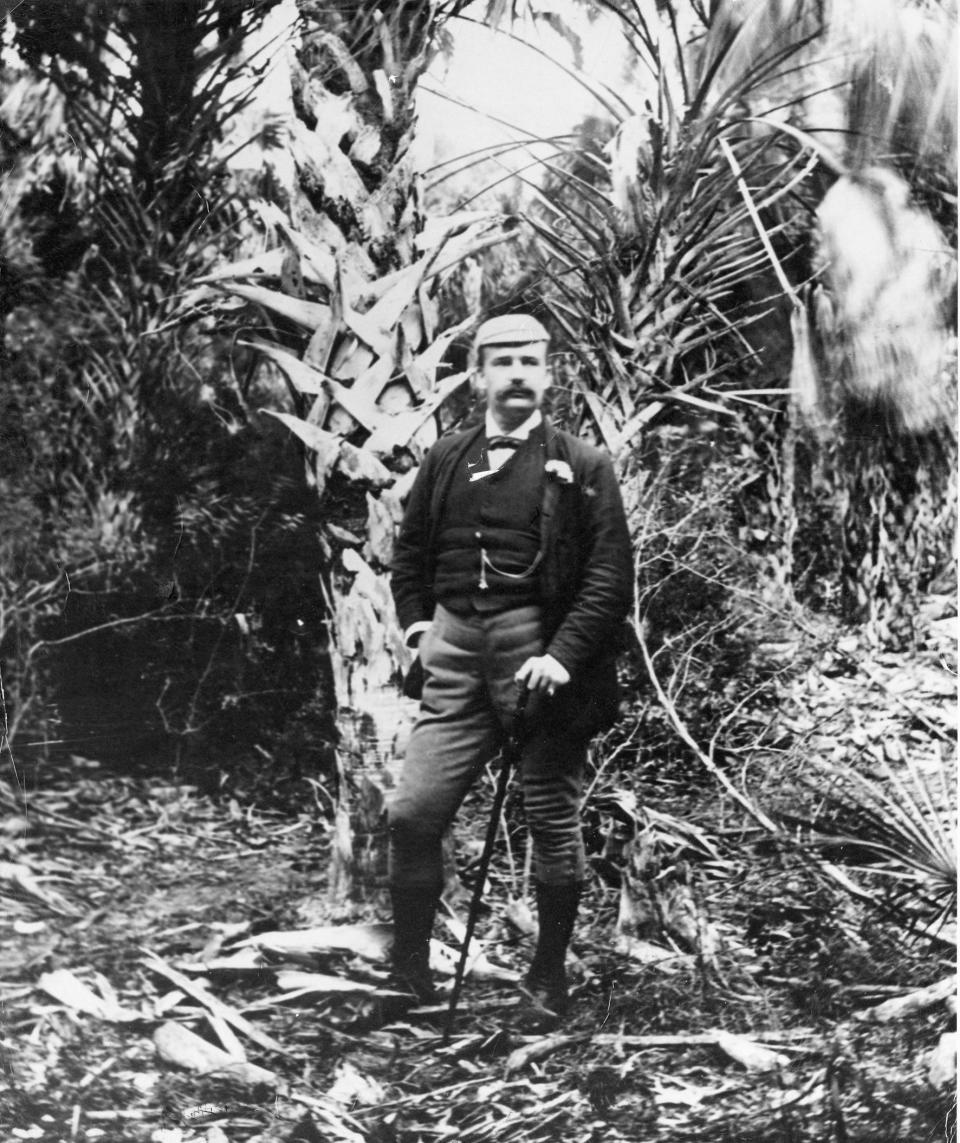

The weather there was clear and bright. Browning reminisced: “Here was the tropics, sure enough; palm trees growing wild along the shore with flowers and palmettos.”

In Fernandina they were beseeched by locals to stay on and make it their home; assuring that with the ship connection to New York and the rail line recently completed it would soon be a prosperous town.

But their own town was awaiting them in Sarasota, and they pushed on by way of a narrow gage railroad to Cedar Key, stopping first in Gainesville.

It was a rough and dusty ride aboard primitive train cars which were described as small and uncomfortable, with frequent stops for fuel for the wood burning engine. The women decorated the train with palm fronds and flowers.

Lawrie recalled that the 110-mile trip took 10 hours, stopping for wood, to gawk at a trained bear, and to look at an orange grove.

They spent the night in Gainesville, in small rooming houses, talking to the locals and exploring the area. Some of the men played pool. Here, too, they were asked to stay on. But after a hearty breakfast they pressed forward to Cedar Key, their small train chased after by cowboys on horses, whooping and waving their hats as they galloped along.

Their stay in Cedar Key provided a restful respite from their long journey. They were cheerfully welcomed and put up at two hotels, one, the Suwannee, was constructed of coquina.

Browning recalled that they were serenaded by African-Americans who passed the hat for tips and said “Thank you kindly,” when a coin was dropped in.

Lawrie wrote of “the kindly southerners” who put on an entertaining ball demonstrating the Virginia reel and other American dances. The favor was returned the next night as the Scots danced the Highland Fling, the Sailors Hornpipe and the Sword Dance, with one of the troop letting out “a wild whoop.”

It was at Cedar Key that the first inkling of trouble surfaced. They learned the disconcerting news that the lumber for their portable homes had not yet been sent on to Sarasota.

After two pleasant weeks filled with hunting, fishing, and mixing with the townspeople, hotel bills and food costs were mounting, and the colony was anxious to push on and begin their lives anew in Sarasota.

The side-wheel steamer, Governor Safford, had been hired for the final leg of their journey. After bidding farewell to their newly made friends, the group boarded the boat at night and set off for Sarasota.

According to Browning the Governor Safford was a “small steamer with small cabins, cushion benches, no stateroom or dining room – only a galley that offered coffee, crackers and cheese.”

The voyage lasted throughout the night, reaching the keys of Sarasota the next day. Along the way, Sutherland (today known as Palm Harbor), the site of another Scot Colony, was pointed out to them. According to Browning, the Duke of Sutherland purchased thousands of acres to establish a colony there.

As the long journey neared its end, it was past the Egmont Lighthouse and through Sarasota Pass. So heavily laden was the boat with cargo and passengers that it was necessary to wait for high tied to get over the sand bar, and pole between the keys.

Late in the afternoon the hopeful colony finally made landfall. What they observed from the steamer’s rail was distressing – no “Little Scotland” here, but, instead, an uninviting wilderness. As Browning put it, “Of course there was much discontent, being dumped like this, in a wild country, without houses to live in; tired and hungry, one can imagine what it was like.”

Some planks were laid in the water for the crestfallen group to disembark. Settlers such as the Whitakers, Abbes, Tuckers and Tatums were on hand to help them unload their belongings.

Canvas tents were erected for temporary shelter, a bonfire was lit, and the distraught men, women and children commiserated with one another.

Lawrie asked one of the settlers what he thought of the land for farming. The reply was a drawled: “Waal, what the (drought) don’t kill, the sand flies get and what they leave the red ants get.”

Ill prepared for the harsh realities of frontier life, the colony failed in short order. As Lawrie succulently summed up the situation, “At last we were at our destination but not at our hearts’ desire.”

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Jeff LaHurd: Rough start for Sarasota’s Scottish settlers