Real History With Jeff LaHurd: When oil fever struck Sarasota

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As the defining year of 1925 rolled into 1926, giddy New Year’s Eve revelers, blowing horns and throwing confetti, could be forgiven for thinking the good fortune of growth and development would continue to roll on. There were grand celebrations throughout the county.

After all, growth had been increasing, with 1925 the strongest year yet.

The front page of the New Year’s Day Sarasota Herald, 1926 recounting all the spectacular gains seemed to underscore the notion. Under the banner head “CHAS. COULTER COMING TO VIEW OIL SITUATION” ran an article noting that there was cause for cautious optimism.

Just below that another headline told of the Grand Opening of Owen Burns’ the El Vernona Hotel, the largest, most unique and lavishly appointed in Sarasota.

In spite of such optimistic news, growth was slowing, needing only the pinprick of the Hurricane of September of 1926 to deflate the good times.

Only the momentum of the previous year enabled the completion of the Sarasota County Courthouse and the new Sarasota High School.

Editorials assured that the thriving real estate marked was more than a speculative bubble. Gov. John Martin wholeheartedly agreed.

But the boom was decidedly over.

Oil offered another possibility to keep the party going.

The chance that pools of black gold waited beneath Florida sands to be tapped and spew forth liquid bullion was headline news. And anyone so inclined could play oil prospector. It was as easy as writing a check.

Tapping a gusher at a time when Sarasota was beginning to feel the pains of an economic downturn would be another bright jewel in John Ringling’s crown; newcomers would certainly follow the news that wealth awaited beneath the sands of Sarasota.

He set up Ringling Tract No. 1 in Sarasota, twelve miles east of Englewood.

Mister John played his cards close. When asked about the prospects for oil, he allowed, “That is a matter of which I know as little as you.” The go-to guy was Kenneth Hauer, president of the Associate Oil and Gas Company. Hauer was less reticent. Initially, he conceded only that it was “the earnest hope of every citizen that oil in huge and paying quantities may be struck.”

Later he was disposed to spout, “Should oil be found, and we are certain it will, the first so-called boom will be as a gentle zephyr compared to a cyclone.” To quote the comedic actor of the day, Joe E. Brown, “WOWEE!”

Hauer had hired “internationally renowned” petroleum geologist Dr. Charles Coulter as a consultant. It was he who had determined the site of Ringling’s oil field.

Hauer backed up his optimism with a statement from the American Petroleum Institute which said there was a “100 Per Cent Oil Possibility in Florida.” Of course, there is a 100% possibility for anything.

The revelation that Sarasota could be on the cusp of another boom was headline news.

The spudding-in ceremony was scheduled to begin with a crash of cymbals on March 13, 1927, and the Sarasota Herald was certain that the streets to the derrick would be jammed with cars lined bumper to bumper.

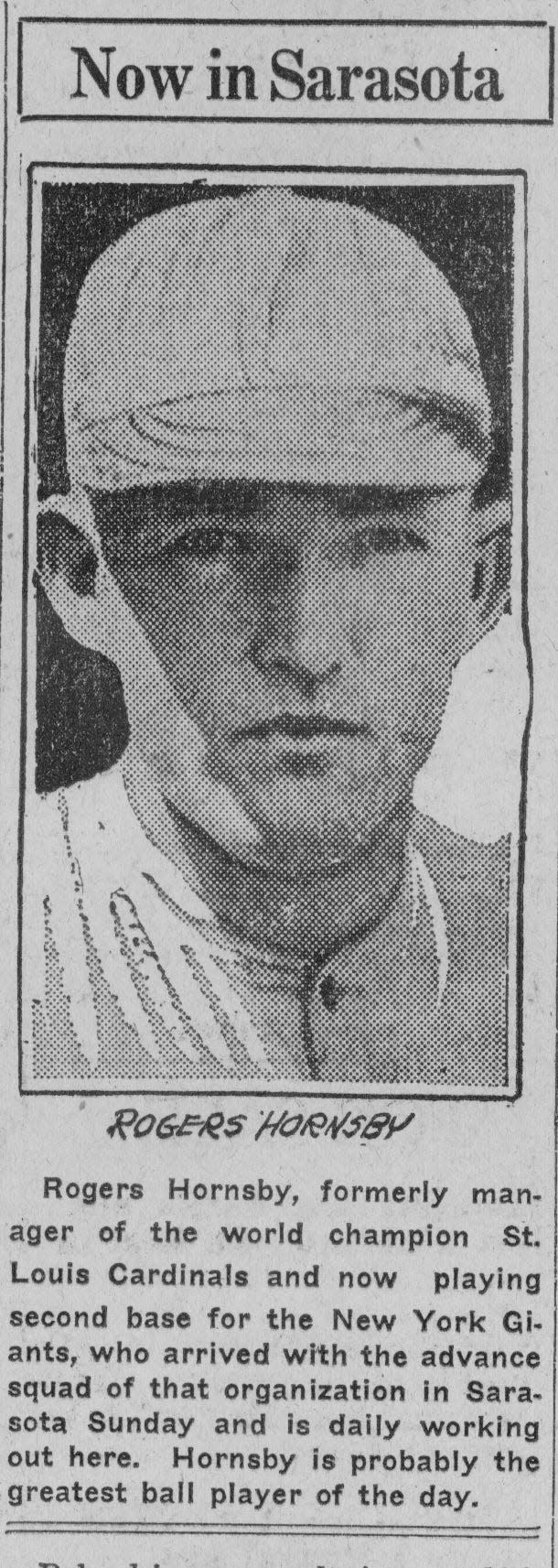

The august occasion was marked by the appearance of Rogers Hornsby, the New York Giants “baseball player deluxe” whom many considered the greatest hitter of all time. He was available to pass out cigars to the gentlemen while Coca Cola and candy was provided to the women and children.

Five thousand onlookers attended the ceremony and reportedly cheered wildly as Hornsby broke a bottle of champagne against the drill bit, “after which the mammoth iron bore commenced its journey downward.” Although the shaft could be sunk to a depth of 6,000 feet, Hauer was expecting to strike “pay sand” between 1,500 and 2,000 feet.

Hedging their bet, The Herald tried to put the possible windfall in perspective: “Florida is not dependent upon the discovery of oil for her future prosperity. Our climate, our seacoast, our soil are our capital. As long as we have these assets, we shall never want for prosperity.”

For some starry-eyed citizens though, the hope of prosperity was the name of the game, a sentiment that Hauer tapped into.

He set up an office in the luxurious Mira Mar Hotel on Palm Avenue, and took out a full-page advertisement in the Herald, complete with a clip and send coupon offering three ways to cash in. It was all very reminiscent of the flavor of the frenetic sales pitches of the crashed real estate market.

Prominent in one ad was a photo of a gusher “running wild” from a well in, of all places, Smackover, Arkansas. (In case you were sleeping during your American Geography class, Smackover is near Norphlet. Today the community celebrates its auspicious gusher with the annual Oil Town Festival, while Oil Field Park is a must-see if you happen to be driving through.)

Hauer enthused, “Suppose – Just SUPPOSE – We should strike a Gusher Oil Well on the Ringling Tract. You may take out a bankroll!” Casting a wide net, he offered three ways to ante up:

1. 5- to 80-acre tracts could be leased for $12.50 to $20 per acre.

2. $50 would buy a fortieth of a share in 4 leases, offering “4 chances to win.”

3. For the financially timid, a $10 flyer would buy one two-hundredth interest in 4 leases; akin to a scratch-off lottery ticket.

Oil fever soon spread to Venice. The Community Oil Corporation was formed, composed of locals “having become convinced that there is oil under Florida.” They purchased their own drilling equipment and sought investors. “We do not ask anyone to put their ‘meat and bread’ money into this proposition, but we so feel that the ones who take a chance ... stand a mighty good chance of becoming rich.”

In the end, it was all for naught. Oil never flowed – never even trickled – and soon Hauer was selling the drilling equipment from an office in Cincinnati, far away from the smelly sulfur water that sprung from Ringling Tract No. 1. It’s been lost to history how many risked their “meat and bread money” for a chance to become oil rich.

Ever the optimist, Hauer’s for-sale flyer noted, “This is a rare opportunity for the right person to start an oil well. All this equipment can be set up on a new location in a week or ten days – ready for drilling operations.”

Jeff LaHurd was raised in Sarasota and is an award-winning author/historian.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Jeff LaHurd: Sarasota’s brief fling with oil prospecting