Real History With Jeff LaHurd: If past is prologue, tree advocates face tough battle

If you are surprised that a 200-year-old oak tree may be felled, you must be a newbie. Welcome to Sarasota.

Named by Arlington Park residents, Pink Floyd gets its name from its location on Floyd Street and a pink ribbon tied around its trunk indicating that it might need to be removed.

Not surprisingly, residents there want it preserved. According to an article in the Patch by Tiffany Razzano, vigils are taking place on Friday evenings and a petition to save the iconic tree is making the rounds.

Razzano quotes longtime preservationist Lorrie Muldowney, who lives in the neighborhood: “For those who have lived here a long time, it’s a natural landmark, a tree I have personally admired over the years as I’ve walked the neighborhood, and it makes this place special.”

Muldowney believes that if the city the neighbors and the developer work together a solution can be found to save the aged tree.

I would love to think that is true. I hope it is. But we have been down this road, and at the end of the street, the ax-man has always won out. Petitions have not mattered, nor has public outcry.

We have the Memorial Oak trees as an example, and more recently the Australian pines.

One would hope that a memorial to the men and women who fought and died for their country, would, by definition, be permanent. Not so. At least, not in Sarasota.

A late as the 1950s, a stroll along Main Street from Orange Avenue east to the Atlantic Coastline Railway Station (gone, too) was like a journey through a Norman Rockwell painting. There were homes with porches, nicely kept lawns, and people to greet as you walked by. A buffering strip of grass divided the sidewalk from the street and in the evening, old-fashioned domed streetlamps cast a comforting glow. But most pleasing of all were the majestic oak shade trees that lined the way.

After World War I, when Sarasota’s boys came home, a sign was painted in the center of upper Main Street near Five Points: “Welcome Home Buddies.” And the stretch of Main Street east of Orange Avenue was renamed Victory Avenue.

To further honor the young men of Sarasota who had fought in the “war to end all wars,” a grateful community headed by the Woman’s Club decided to pay tribute by planting an oak tree, one for each of the 181 who had fought the good fight. The club’s gesture was done for love of country and to demonstrate their appreciation for the services of the gallant young men who helped make the victory possible

At the dedication of the trees in 1922, Woman’s Club president, Mrs. Frederick H. Guenther, standing in front of Sarasota High School, then on Main Street, promised that the memorial was “an avenue of living trees, whose beauty and grateful shade would delight and bless generations long after you had passed on.”

Indeed, by 1954 they had grown full and lush. For some, that was a problem.

Leaders of Sarasota, always pushing the city forward, determined that the trees were standing in the way of progress. City Manager Ken Thompson told a reporter, “The presence of trees along Main Street has undoubtedly curtailed development of the city’s main street as a business street.” A city commissioner was even more blunt: “It’s either the oaks or progress.”

As with the Arlington Park neighborhood, not all agreed, and the battle was enjoined. Did shade trees really impede progress? Some members of the community thought not. Civic leaders Karl Bickel, and his wife, Madira, were world travelers. He the founder of United Press, reminded that such grand cities as Rome and Paris had trees along their boulevards and were proud of them.

Madira, former president of the Sarasota Garden Club, said that city beautification was as important to civic progress as new streetlights and swimming pools.

The battle turned into a full-fledged war. Friends of Friendly Oaks was formed and waged a campaign to save them. Petitions were signed, money collected, commissioners were lobbied. The News editorialized strongly in favor of their salvation.

An expert from the University of Florida was called in and pronounced the trees healthy. He said that removing them would be foolish.

The president of Maas Brothers Department Store, Jerome Waterman, promised that ten oaks bordering the site of a new Maas Brothers would be spared. The News thanked him by saying he had “earned the gratitude of the entire community.”

Soon all the local newspapers were full of the controversy. An editorial in The News on Jan. 5, 1955, said, “We’d rather keep the oaks and let business plan to include them in its growth.”

But on January 7, The News reported, “First of Memorial Oaks Topples to Progress.” The next day, under the bold headline “CITIZENS!!!” the Friends placed an advertisement that asked, “Can the will of a few rob Sarasota of its heritage, its lovely avenue of shade trees? Will the center of Sarasota be left to broil in the blazing sun like a factory town?” A “Spare the Main Street Trees” coupon was enclosed to clip and mail.

But protestations notwithstanding, one by one the trees were felled. Today there is no longer any mistaking of Victory Avenue (Main Street) for a Rockwell painting. And if you stroll that stretch of concrete on a hot summer day, you may wish that city leaders had heeded the Friends of Friendly Oaks and built around Mother Nature and not over her.

The Australian pines were next. Many believe the trees, which are considered an invasive species, negatively impact the local environment and can be a safety hazard during storms. But for many years they were seen as a most efficient means of beautifying the area. And they were planted EVERYWHERE.

John Ringling brought them to Sarasota to line Golden Gate Point, which was dredged and filled to be the starting place for the first John Ringling Bridge; they lined the entrance to Bird Key that Ringling had linked to the mainland, also along the Ringling Causeway, the entrance to St. Armands, and around the circle. They were planted on Lido Key and Coon Key. There were thousands of them, and they grew fast, forming a lovely green breaker offering much needed shade.

In February of 1926, as the John Ringling Bridge was opened to the public, the Young Business Men’s Club, “working for a clean and beautiful Sarasota,” decided planting trees was a worthy project and members elicited support from other local clubs to join them.

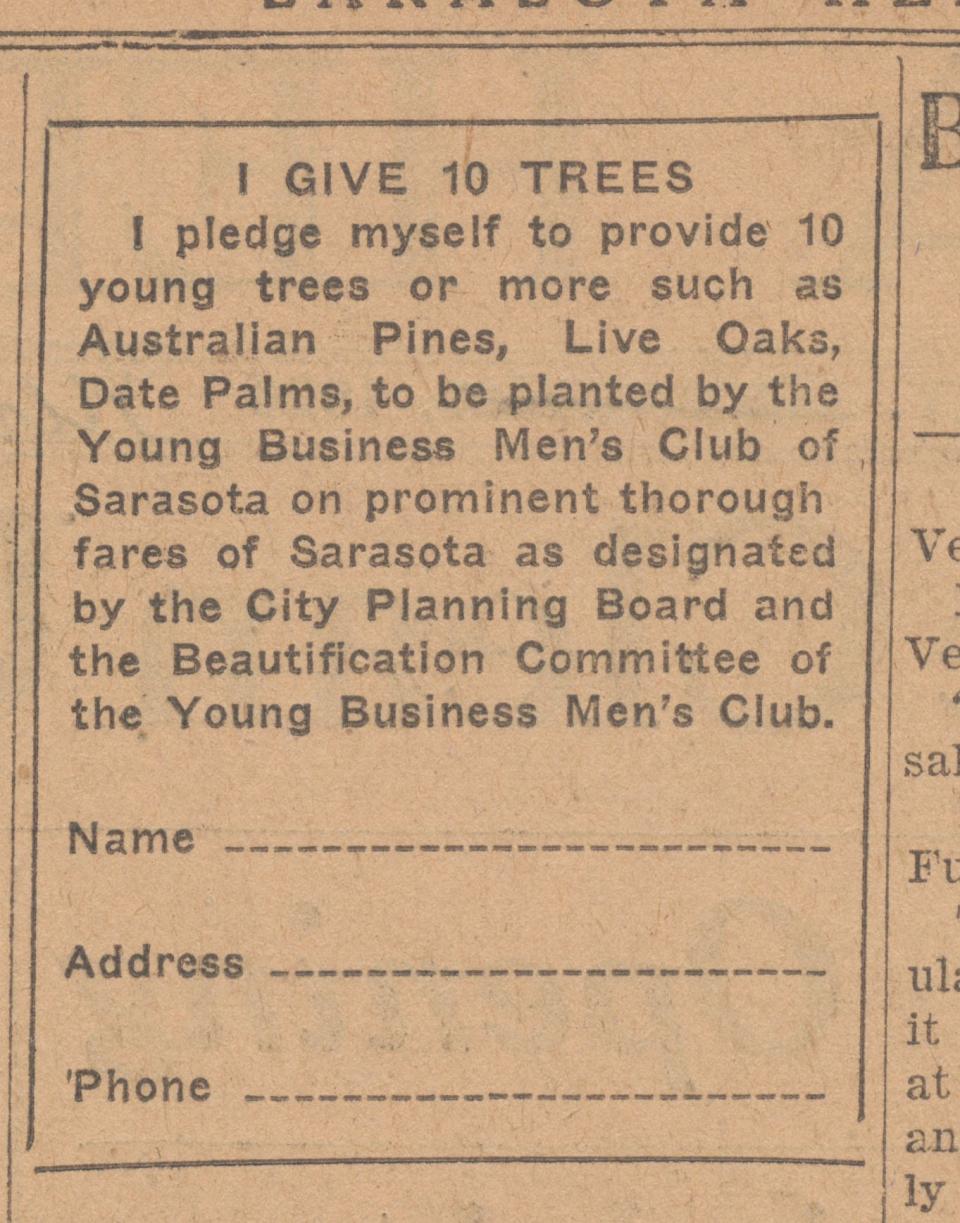

A small coupon in the Herald could be clipped and sent in with a pledge to plant 10 trees, including the Australian pine, which would become “a panorama of beauty to the eye.” They trees were easy to purchase. A downtown nursery on Orange Avenue advertised them as great for windbreaks, party lines, lawn shade, and hedges: “The Australian pine has no equal.”

They were planted throughout the county. In 1942, a garden club at the Sarasota Mobile Home Park at Payne Park planted 463 Australian pines, and during Beautify Sarasota Week, sponsored by the Men’s Garden Club in November of 1954, the club planned to replant some of the “stately” Australian Pines that had been damaged on St. Armands. The Herald reported that the trees, “which help to make the key area one of Sarasota’s show spots, are to be re-worked to create an arching effect.”

Up to that point, the tree had caused no major tragedies; they seemed not to be the bulwark against progress as were their oaken brothers, falling limbs had not maimed passersby.

Other than standing tall and lush, requiring the occasional thinning out, or removal when killed by frost, they seemed to be pretty much minding their own business; hoping the ax-man would do the same.

It was not their fault when Zuka, a Rhesus monkey, point of origin unknown, kidnapped two kittens and scampered with them to the top of one of the trees to escape. High above the posse, she hung from her tail, “clutching the cats tightly to her skinny bosom.” But even that story ended happily as the kittens accepted Zuka as their mother.

For the most part, people appreciated their beauty and wanted them protected. In 1953, when the State Road Department authorized cutting the pines lining Longboat Key, residents there, with the cooperation of the Garden Club, protested their removal and the state temporarily stopped cutting them down.

Ten years later, residents of Bird Key, and St. Armands Key “flooded” the telephones of local officials when the pines on Coon Key were about to get the ax. A representative of the Bird Key Garden Club noted “many retirees were attracted here [by the pines]; coming from the treeless, concrete metropolises of the north.”

In December of 1963, it was reported that Frederic B. Streasau, the city‘s consultant landscape architect, recommended keeping as many of the trees on the John Ringling Causeway as possible. He said, “The Australian pine is one of the few plants that give us a skyline silhouette. Even though they are dirty, brittle and costly, they are the best thing we have.”

The trees planted by the Sarasota Mobile Home Park in 1942 were damaged by Hurricane Donna in 1960 and killed off by the freeze of December 1962. Some had grown to over 90 feet and Herald columnist Martin O’Neil lamented, “Shade suddenly was lacking,” a theme that is repeated each time they are in harm’s way. No trailers had been reported crushed beneath them, no escape routes blocked off.

Not everyone was a fan. Their rapid growth, once a selling point, their “ground litter” and “intruding root system” and their vulnerability to cold weather kept them on the ax-man’s mind.

An aerial taken in 1965 reveals that practically all the trees on the keys and Golden Gate Point had been removed. In 1984, some 1,500 of the 3,000 trees that reportedly occupied the seven county parks needed to be cut down. Of these 30% were already dead, and 50% were dying. There was concern over falling limbs.

The battle to save the trees was taken up by longtime resident Carole Nikla, backed by many residents who recognize the trees’ iconic status in the community.

For the pro-Australian pine group, the tree is a part of the Sarasota scene to be protected and appreciated; not an invasive species for the woodman to eradicate. But they do choke out native species that might more readily grow under, for example, a stately oak such as Pink Floyd.

Perhaps an unattributed quote in Razzano’s article sums up Sarasota’s position on preservation: “He [the developer] doesn’t care. He just wants to make money for himself and a name for himself,” said the unnamed advocate for the imperiled Floyd Street oak. “He doesn’t care about this beautiful tree that has been here for longer than any of us.”

Jeff LaHurd was raised in Sarasota and is an award-winning author/historian.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Jeff LaHurd: Sarasota has a habit of felling trees