Real History with Jeff LaHurd: Sarasota’s early schools

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The parents of school age children during Sarasota’s frontier period could be forgiven for not putting education at the top of their to-do list. Life was a hard, labor-intensive struggle just to survive the hardships of day to day living. Everyone in the family did their share to keep the homestead going.

Under such circumstances, formal education took a back seat. Families who could afford, hired a live in teacher for their children and other children in the vicinity.

Classes were taught in the home, in an abandoned fishing shack near Hudson Bayou, or a barn. Among the earliest photos of Sarasota students in a class setting shows Professor Brush, a rather stern looking fellow with a close-cropped beard and short hair, with his students in a backyard. Brush gives the appearance that he would not be amused with horseplay.

The first constructed school in Sarasota was downtown near Pineapple Avenue, a rectangular building built free of charge by volunteers using wood donated by John Hamilton Gillespie, the first mayor. Its teachers were Anna and Sue Whitcomb, sisters who were related to the great poet James Whitcomb Riley. They taught for free, and the children who managed to attend sat on roughhewn benches and wrote on slates. There was no heater. Years later, longtime resident Dave Broadway recalled it as a shack.

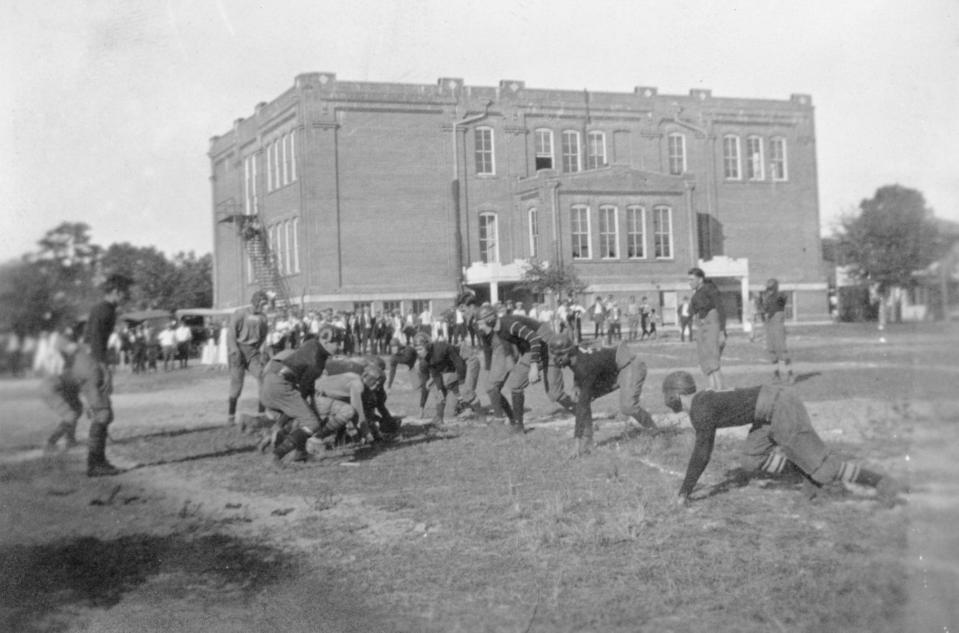

As the town grew, a new schoolhouse became necessary. In 1904 a $3,500 two-story building was constructed on Main Street and Pine Avenue. It offered five classrooms and a second-floor auditorium. One hundred and twenty-four students were enrolled on the first day of class.

Sarasota’s population continued climbing, necessitating a larger school. This was a red brick structure located on the property of its smaller predecessor which was moved nearby. Erected in 1913 for a cost of $23,000, it offered eleven classrooms and an auditorium. It soon proved inadequate, and the original school was pressed back into service and utilized for first through third grade. (When this school was demolished in the 1920s, some of its bricks were used for pathways at Sarasota Jungle Gardens.)

The community was hard pressed to keep teachers in the classroom as their wages were set at a paltry $50 to $55 a month, barely enough to subsist. Parents also gifted foodstuffs to help them out. At the Old Miakka school, during the Great Depression, “the teacher would bring a pot of meat to school each day, and the children brought ingredients to add to it: an onion, a potato, or some cabbage. They would put it all into a pot on the wood stove. By lunchtime they had a stew.”

Rose Wilson, editor, and publisher of The Sarasota Times, along with the Woman’s Club began to crusade for compulsory education for Sarasota’s youngsters. “Give every child a fair deal,” Wilson editorialized. When voter turnout was low, she used it to underscore another of her passions – the right of women to vote. She assured her readers the school issue would have brought women to the polls in substantial numbers, and it would have passed.

When Mrs. Velma Tatum retired from teaching after a 29-year career in elementary education, she recalled the curriculum for the younger children revolved around the “Three R’s.”

She graduated along with 17 classmates from Sarasota High in 1923. Their class picture shows them on the front steps, outfitted in their Sunday best. This was the largest graduating class in Sarasota’s history up to that time.

For her to qualify to become a teacher it was only necessary to pass a three-day exam which was given in the office of longtime school superintendent Thomas Yarborough.

Among her many memories she recalled that classroom teaching was only a part of the job. She also functioned as counselor, nurse, chauffeur, mother and occasionally barber.

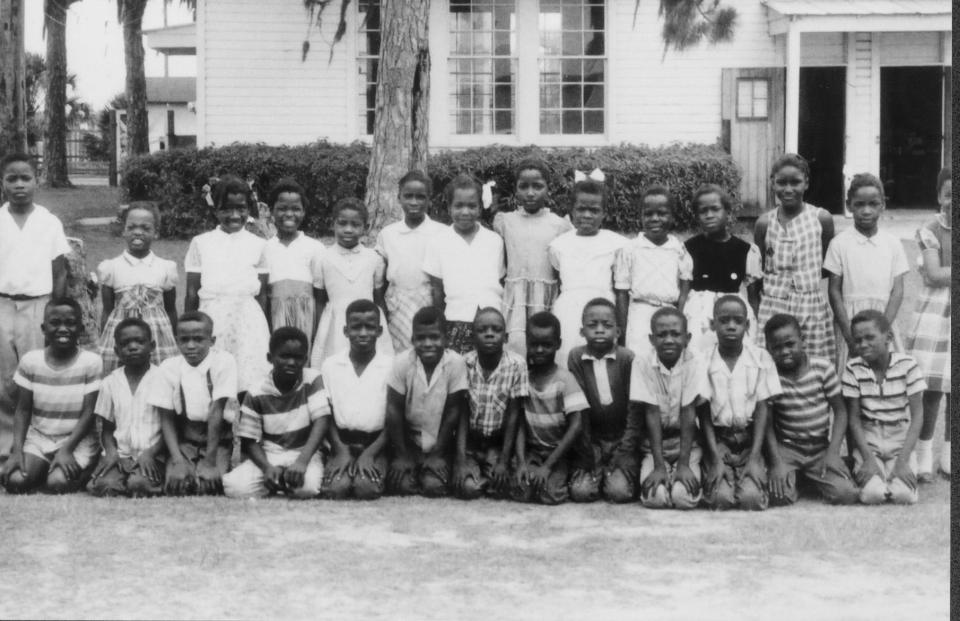

Sarasota schools were still segregated and educational plants and equipment for the Black population were subpar. Sometimes crates served as desks; hand-me-down books and used supplies had to suffice.

In 1925, thanks to funds from the Rosenwald Foundation and the efforts of African American educator, Emma Booker, a driving force for the education of Black children, the Sarasota Grammar School was built to serve centrally located students. South County children went to the Laurel Colored School.

For many years, classes went only to the eighth grade for Black students in Sarasota. Further education was available for them in Tampa or Fort Myers, a difficult trek sometimes underwritten Ms Booker. For her years-long battle for black children, Emma E. Booker Elementary School, Booker Middle and Booker High School were named to honor her memory.

With the boom of the Roaring ’20s and its influx of newcomers, a wealth of new schools was built, reflecting the Mediterranean Revival architecture of the times. Central Elementary School was finished in 1925. The twin schools of Bay Haven and Southside Elementary were opened in 1926 at a cost of $77,000.

M. Leo Elliott was responsible for the Collegiate Gothic Revival architectural style of Sarasota High, which began graduating students in 1927.

That building, now beautifully restored and serving as Sarasota Art Museum of Ringling College, stands as a testament to preserving old landmark structures for re-use.

The simplicity of a curriculum based on the “three R’s” had been enhanced in high school; including a formidable, head-scratching array of science, literature, math, geography and philosophy that would challenge a college graduate.

A few examples. Tenth grade classes: Composition and Rhetoric; Classics; High School Algebra; Walker’s Caesar; Physical Geography. Eleventh grade: History of English Literature; Classics; Plain Geometry; Allen & Greenough’s Six Oration Cicero; High School Physics; Civic Government of the United States; Fraser & Squair’s French Grammar. Twelfth Grade: more of the same plus two months of Civil Government of Florida, chemistry and trigonometry.

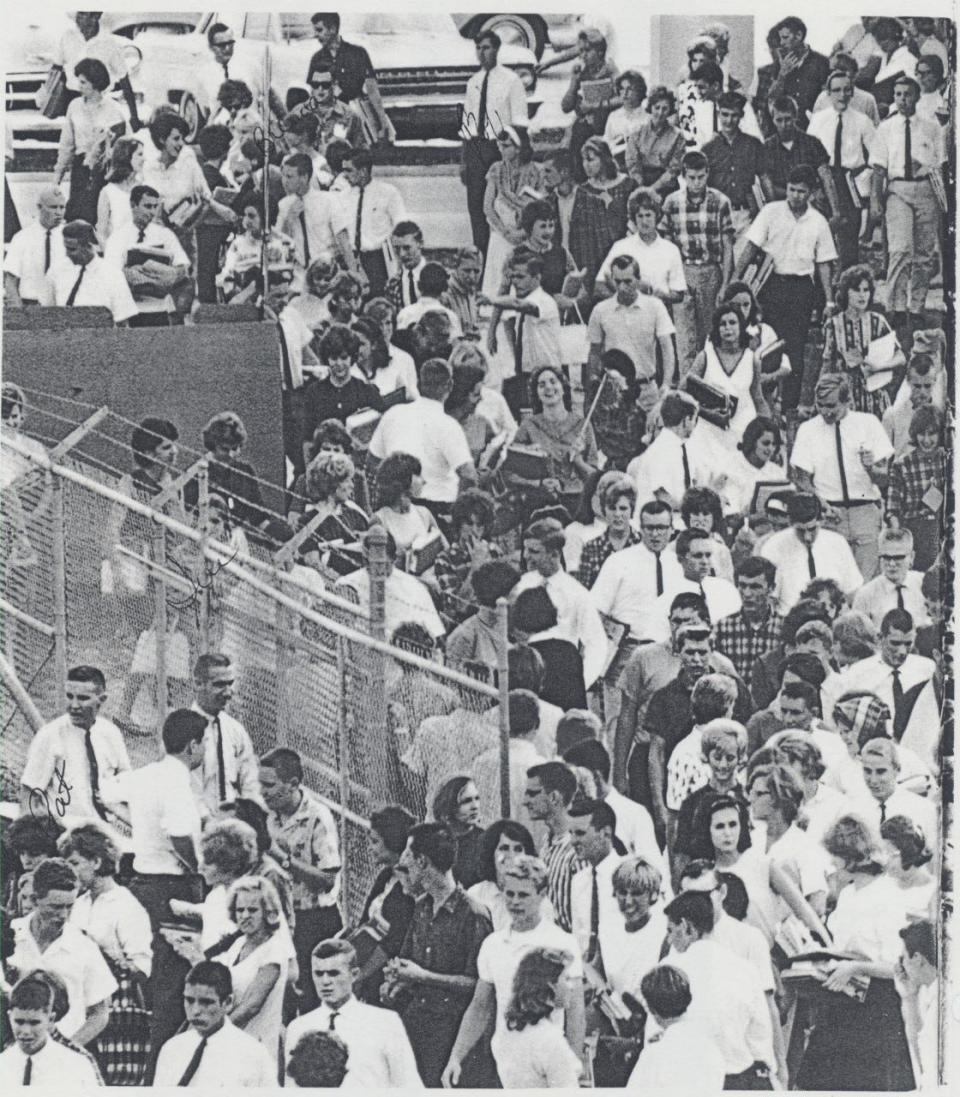

The post-World War II boom emphasized the modernism of the Sarasota School of Architecture. Mentored by School Board Chairman Philip Hiss, a new wave of buildings was constructed; designed by such well-known architects as Paul Rudolph (Riverview High School and the Rudolph addition to Sarasota High); Ralph and William Zimmerman (Brookside Middle); Sellew and Gremli (Alta Vista Elementary); and numerous others throughout the expanding county.

Riverview, founded in 1958, met the needs of students in south Sarasota.

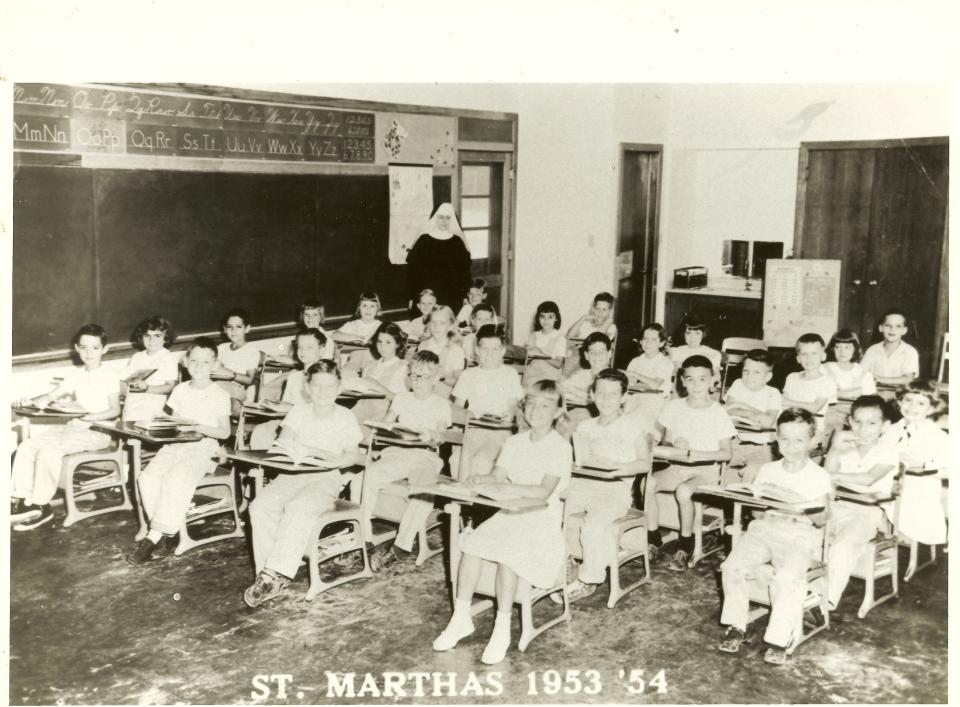

By 1950, there were enough Catholic children in the area to allow Father Elslander to begin construction of St. Martha School. With its combination of teachers of the Benedictine Order (who, like Brush, did not find horseplay amusing. Corporal punishment was not unheard of) and lay teachers, the school grew quickly. Ground was broken for Cardinal Mooney Catholic High School in April 1960.

Curriculums, teaching methods and learning aids change with the times. The common educational thread remains constant, the dedication of the teachers and their love of the profession.

When Mrs. Catherine Radford retired after 40 years in the Sarasota school system, she summed it up: “Teaching has been most of my life. I’ll miss the kids. When you’re contributing to a student’s learning and maturity there is no more important or enjoyable job.”

Jeff LaHurd was raised in Sarasota and is an award-winning author/historian.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Jeff LaHurd: Schools were built as Sarasota grew