Real History With Jeff LaHurd: Spring training from the Giants to the Sox

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Just before the land boom of the ’20s when Sarasota offered fishing, hunting, golf, enviable weather, and bathing – and little else – spring training was seen as a surefire way to promote this little-known community striving to become a go-to destination.

As early as 1912 when the town organized its own baseball team, the Sarasota Times noted the twofold purpose, “to furnish amusement ... and also to advertise the town by having a good baseball team.”

And as important as it was for Florida to attract major league baseball, it was equally as important to keep the owners, managers, and players happy enough to assure their annual return. Baseball was America’s favorite pastime and the snowbirds loved watching the game, the presence of big leaguers boosted the economy, and perhaps most importantly, the accompanying big city newsmen generated free publicity.

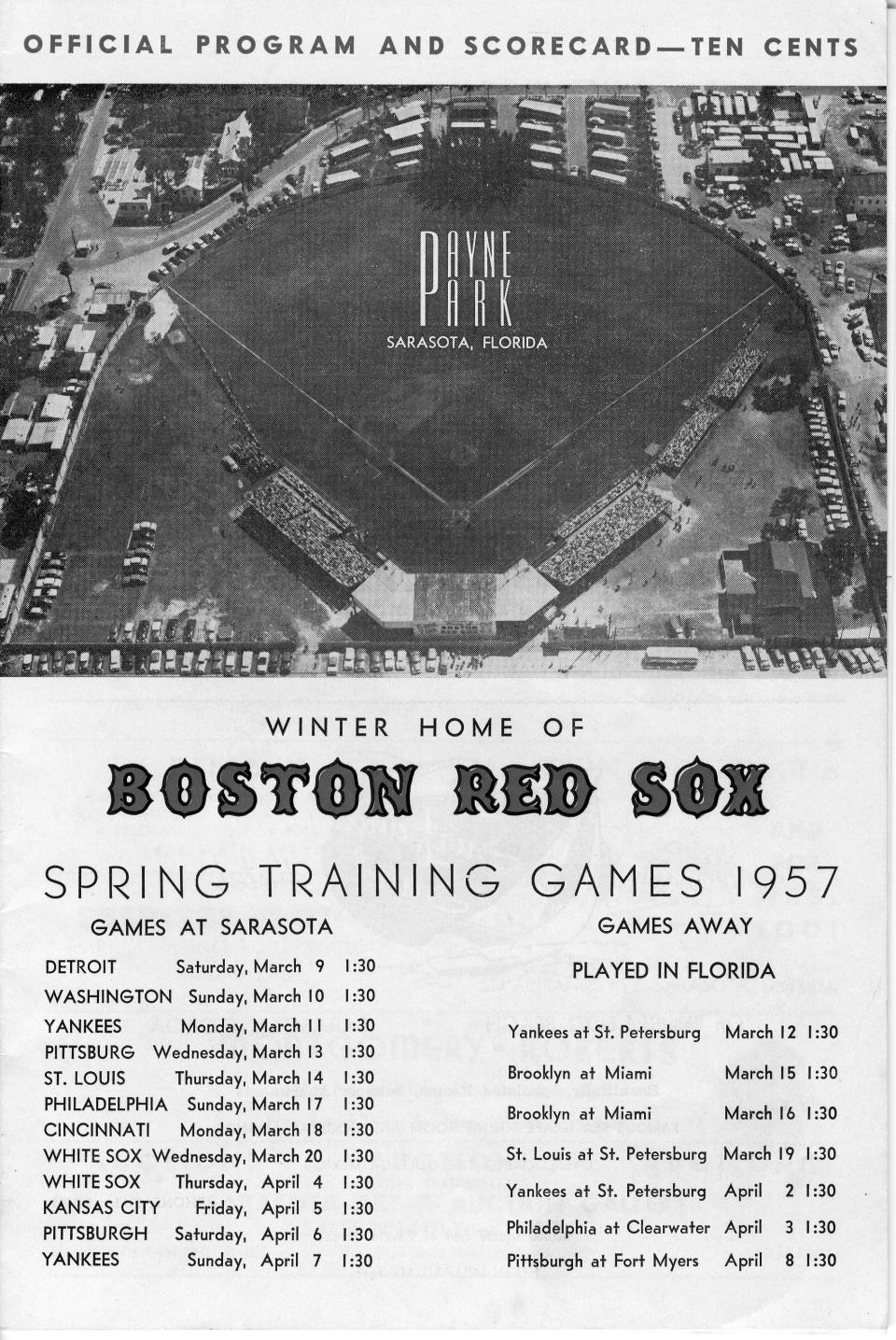

For Sarasota, the first order of business was to build a suitable field of play. The sandlot used by the hometown boys would not suffice. In one of the earliest combined ventures between the city and the recently formed county (1921), Mayor Everett J. Bacon declared a public workday, and citizens throughout Sarasota came together to volunteer their time and talent to construct what came to be known as Payne Park; a baseball diamond with grandstands and a clubhouse.

That mission was accomplished on Oct. 27, 1923, and with high hopes the locals began scouting for a major league team to call it home.

Several teams expressed interest, but it was through the assistance of John Ringling with his many New York connections that Sarasota snagged the mighty New York Giants, a powerhouse team that had won the World Series in 1921 and 1922, and the National League Pennant in 1923.

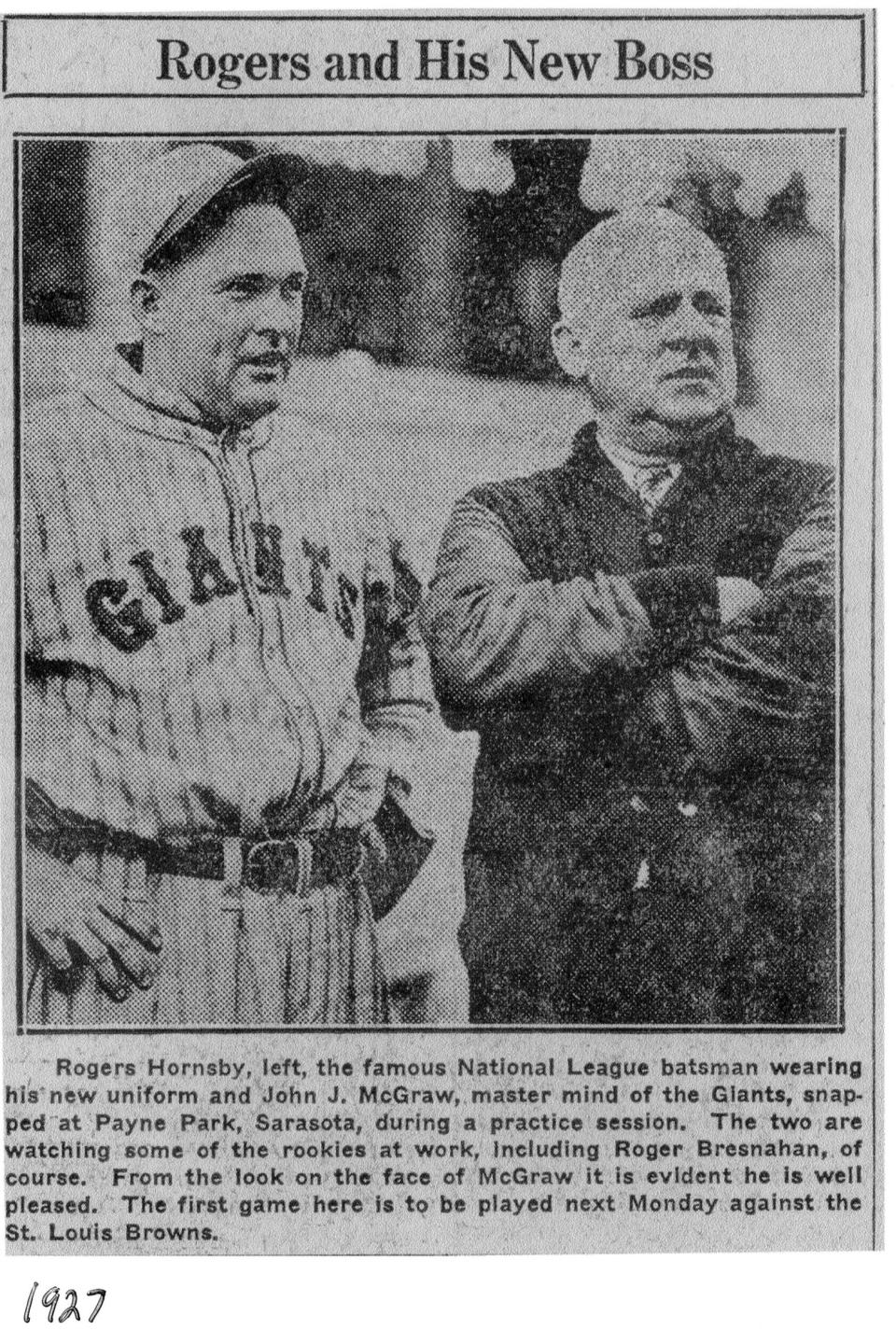

The Giants were led by the fiery and colorful John J. McGraw, one of the greatest managers of all time. He had a firm grasp on how to win games, and his disciplinary approach to running his team – he was tagged “Little Napoleon” – was summed up by him thusly: “With my team I am absolute czar. My men know it. I order plays and they obey. If they don’t, I fine them.”

The first order from McGraw was to prohibit his players from playing golf. The golf ban would have bothered slugger Rogers Hornsby not at all. Hornsby played with the Giants in Sarasota during the 1927 season, the team’s last year here. He won seven batting titles, six of them in a row, was a two-time MVP and had a .358 lifetime batting average during his twenty-three-year playing career. As a player/manager for the Cardinals he won the World Championship in 1926.

As for golf, Hornsby did not participate. He offered that when he hit a ball, he wanted someone else to chase after it. And hit them he did. He was quoted, “I don’t like to sound egotistical, but every time I step up to the plate with a bat in my hands, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for the pitcher.”

The Giants played here for only four seasons. McGraw saw the money-making potential in local real estate and took the plunge with a much-ballyhooed subdivision he christened Pennant Park. His timing was off and Pennant Park never materialized. Investors lost money and Little Napoleon decided it was prudent not to return after the 1927 season.

As nationally syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler put it, a return “... would have awakened unhappy memories of an expanse of jungle near Sarasota which Mr. McGraw and some associates were retailing to investors a couple of years ago at very interesting prices ...”

When the Giants quit Sarasota it was an economic blow, and a loss of the type of publicity that you cannot buy. Four years was not really enough time to form a close attachment, and the hunt was immediately on for a replacement.

The chamber of commerce sports committee looked desperately for another Major League team, and as none was available settled for the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association who signed up for the 1929 season.

Again, it turned out to be a four-year stint. The Great Depression had fully griped the nation, and at the end of the 1932 season, the Indians decided it was financially more prudent to train in French Lick, Indiana, closer to their home.

Enter the Boston Red Sox, a team then the opposite of the mighty New York Giants in wins and losses. A former contender for the pennant, they had placed no better than fifth since they won the Series in 1918 and had finished in last place nine times through the 1932 season. The legendary curse of the Bambino was firmly upon them.

But nevertheless, they were a big-league team and their new owner, Thomas Yawkey promised an immediate rebuilding campaign to pull the Sox out of baseball’s cellar.

The team was put up in the Sarasota Terrace Hotel, adjacent to Payne Park which the Sox enjoyed, saying it was “a corker,” and the food “was a revelation ...”

The all-important press reports going back to Boston pleased the chamber of commerce. As one article put it, “Sarasota has proved the best training camp the Sox have had in years.”

At the end of the 1933 season the community showed its appreciation to the team by throwing them a dinner, attended by 120 fans of “the Bean City Aggregation.”

The Herald summed up local sentiment toward the team: “It is the sincere wish of every fan in Sarasota that they will have the pleasure of listening in on the World Series in October and that our good friends, the Red Sox will be representatives of the American League and return. ... But regardless of your position in the race, they will sincerely want you to come back here next year.”

Yawkey responded, “I look forward to many good seasons here.”

Thus began a twenty-five-year relationship between the Sox and Sarasota, a marriage between a town and a team that lasted until one unexpectedly walked out on the other.

Unlike the Giants and the Indians, the Boston Red Sox was truly Sarasota’s team.

The team listed two big guns, Jimmy “Double XX” Foxx who was one of the greatest of all right-handed sluggers, said to be so strong he had muscles in his hair, and Ted Williams, aka “Teddy Ball Game.” He once said his life’s goal was to have people say, “There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived.”

Ted Williams was a Sarasota favorite. His career was interrupted twice during his prime when he served in World War II and the Korean War as a Marine Corps fighter pilot. Of his hitting prowess one of his teammates said of him, “He could hit better with a broken arm than we could with two good arms.” For his part, Williams said of the sport he loved, “Baseball is the only field of endeavor where a man can succeed three times out of ten and still be considered a good performer.” He was inducted in the Hall of Fame in 1966.

And the players were held in high esteem in the community. Particularly Williams, who was an avid fisherman, often spending time at Tucker’s Sporting Goods store downtown.

Boston was in Sarasota through the Depression, World War II and the Korean War, as well as the post-war boom. Locals thought the relationship was forged in steel.

It was not. After a well-attended silver anniversary party throw to honor the relationship, general manager Joe Cronin told the beaming audience, “We have had twenty-five years of happy association with the people of Sarasota and we have no intention of moving our training base to Arizona, California or anywhere else.”

A few months later the headline in the Herald hit like a bombshell, RED SOX TO LEAVE SARASOTA. Sarasota was shocked. Perhaps City Commissioner John Binns put it best, “I’m just heartsick over it and indignant at the same time.”

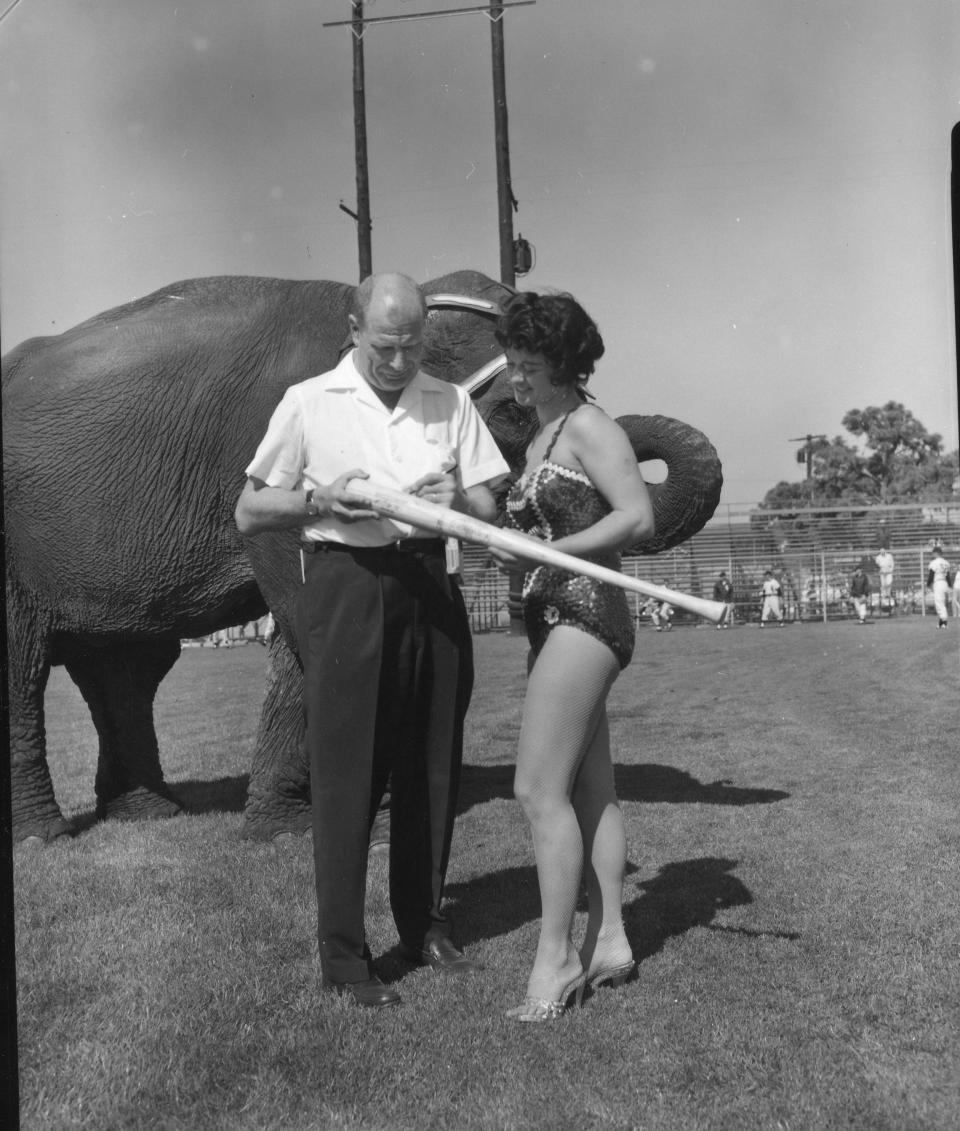

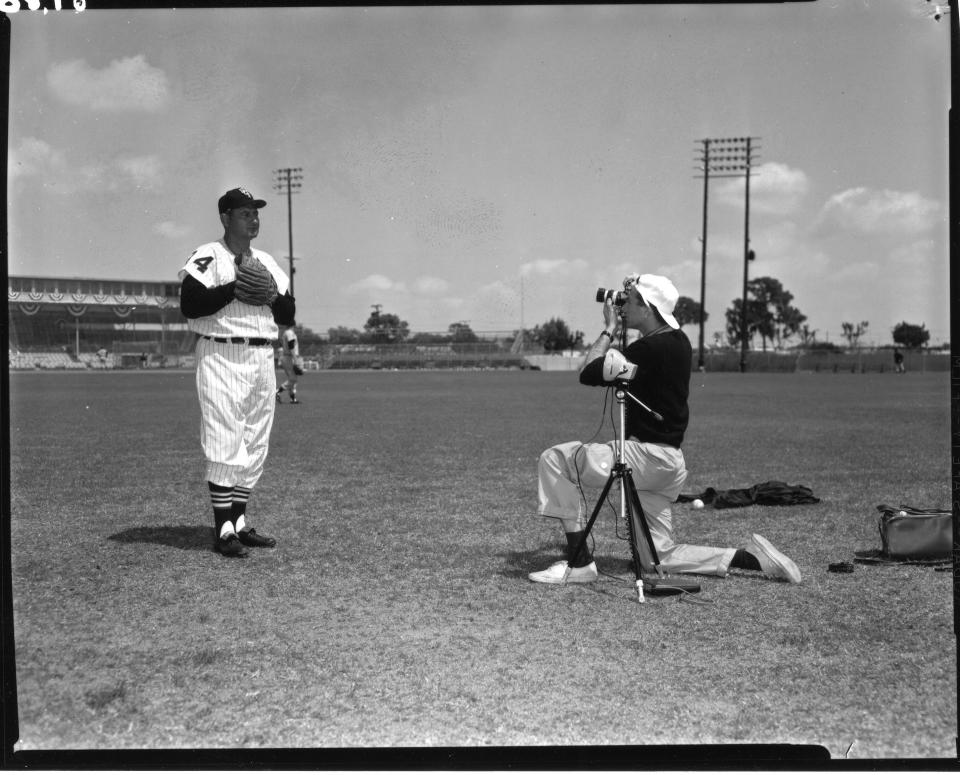

In 1959 the Brooklyn Dodgers played some of their spring training games in Sarasota and in 1960 the “GoGo” Chicago White Sox under the leadership of the colorful personality Bill Veeck signed a 5-year contract to play in Sarasota which stretched to 28. Known as “The Barnum of Baseball,” he once said, “There are only two seasons: winter and baseball.”

The Sox was the last team on which Early Wynn pitched. A tough hombre on the mound, known to brush back players. When asked if he would throw at his mother he replied, ‘It would depend how well she was hitting.”

Arthur Allyn, corporate executive, bought the shares of an ailing Veeck and Hank Greenberg for $2.5 million. He became very involved in the affairs of Sarasota.

The last major league game was played at Payne Park in 1988. The field was antiquated and not up to the standards of the day. For the modern era, Ed Smith Stadium, named for the hardworking multi-year president of the Sarasota Sports Committee, was built and ready in time for spring training in 1989.

Jeff LaHurd was raised in Sarasota and is an award-winning author/historian.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Jeff LaHurd: Sarasota has long history with spring training