Real stories behind the ascension of Hall of Fame quarterback Peyton Manning

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

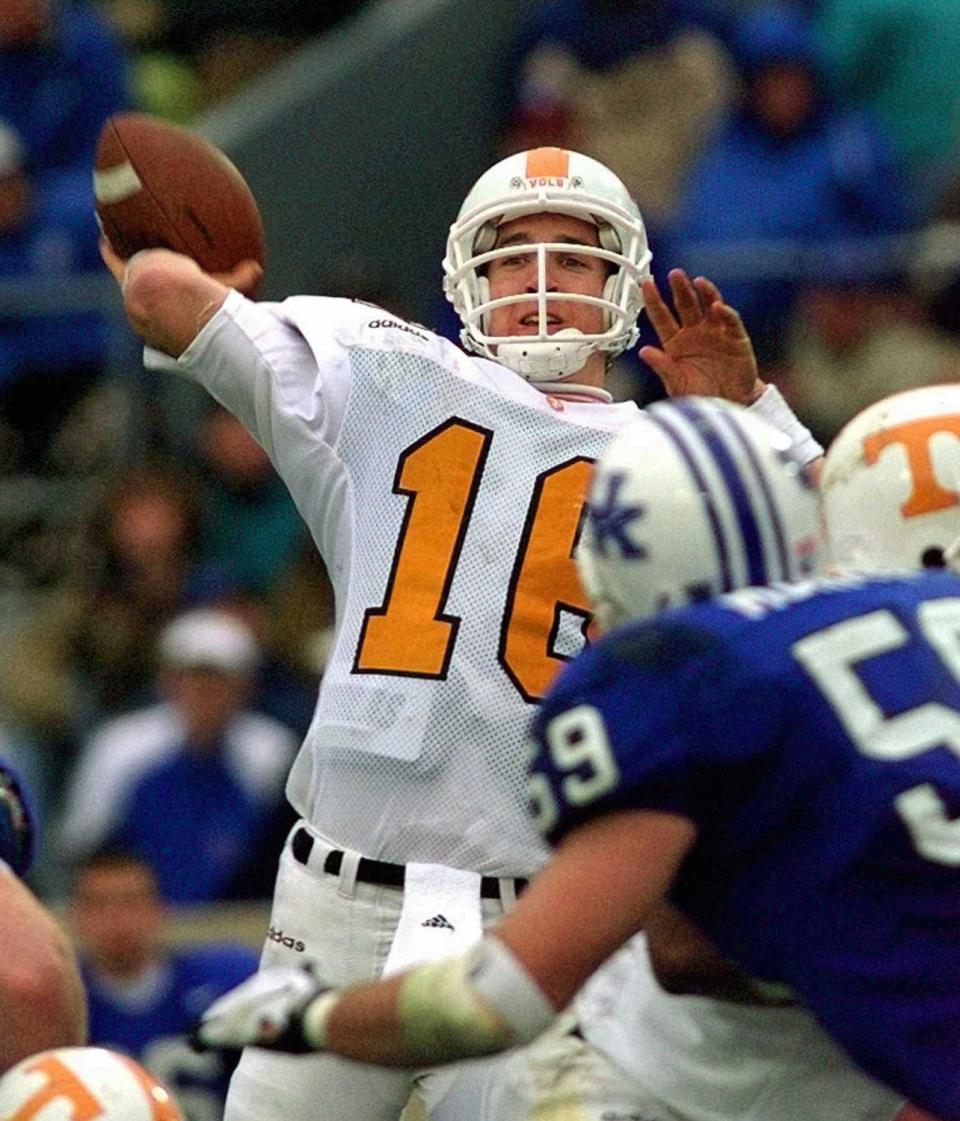

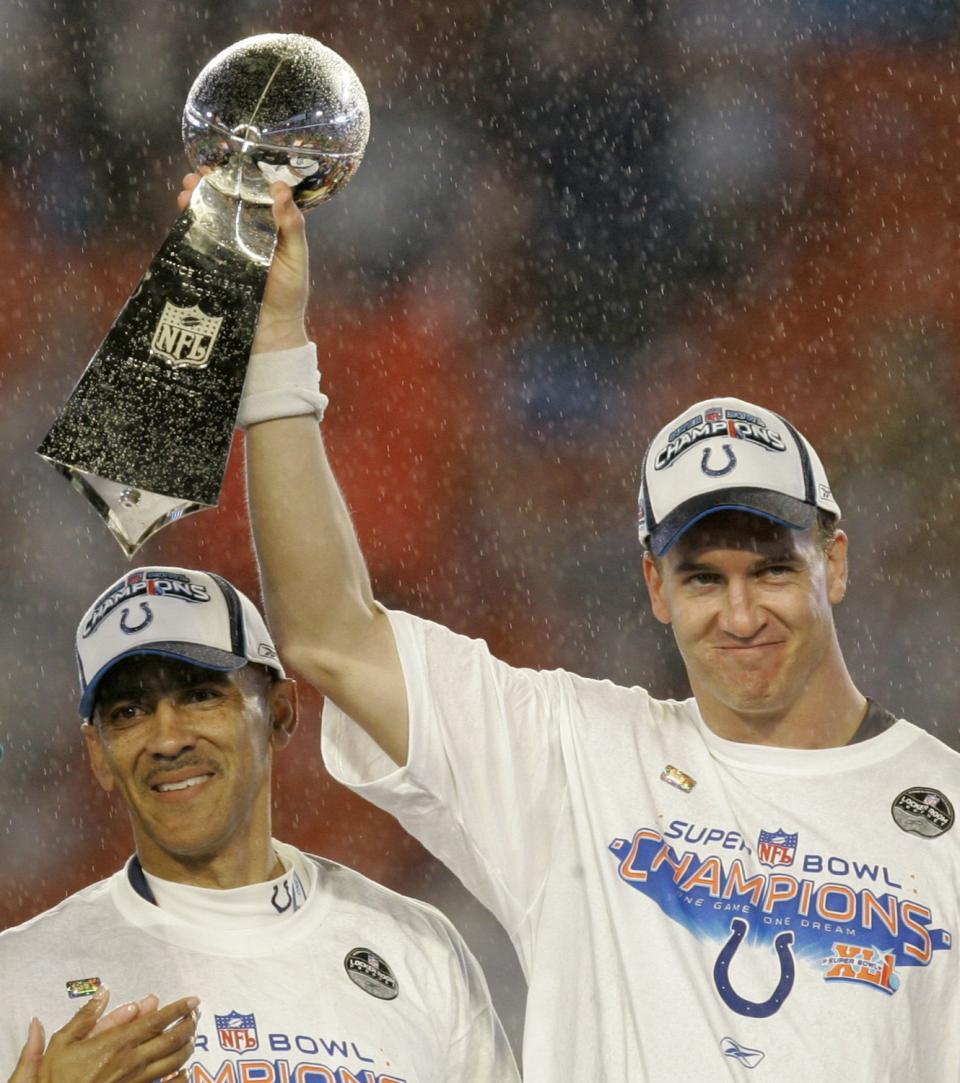

Peyton Manning will be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Sunday, the capstone of a spectacular career in which he directed the Indianapolis Colts and Denver Broncos to Super Bowl victories.

In the audience will be legions of fans, along with friends and former teammates. Some grew up with him in New Orleans, and lined up with him on the sports fields at Isidore Newman School, which is pre-K through 12th grade.

The Los Angeles Times gathered five of his former Newman teammates for a video conference to reminisce about the gangly, plodding, pranking kid who rounded into one of the best quarterbacks in NFL history.

On the call were Manning friends Baldwin Montgomery, Justin Reyna, Thad Teaford, Mike Keck and Nate Stibbs.

“I really value those friendships, and a number of others who I grew up playing Little League baseball with or went to school with at Newman,” Manning said. “I'm proud that I've been able to maintain those friendships for such a long time. They give me a hard time because they basically had an annual trip to see me play once a year either to Knoxville, for a Tennessee game, Indianapolis for a Colts game, or in Denver.

“When I retired they accused me of kind of ruining our annual trip, that I was selfish about retiring and screwing everything up. I took the heat for that.”

Getting together wasn’t easy during the pandemic, but Manning did gather his friends to take in a college game at Tennessee.

“Watched the game, sat in the stands, and had a good get-together. Have to be a little more creative and finding what to do on our annual trip. Football made it easy.”

Among the memories:

Forget me not

Even when he was a kid, Manning’s memory was something to behold. He could recall the smallest of details, and not just sports-related ones. Sometimes it was music.

“Back in those Little League days, sometimes you’d be going to play some game an hour or two away,” Reyna said. “Peyton was with us one time, and my parents put some Motown on the radio. We’re probably 11 or 12. He’s sitting back there naming the songs and who sings them. My parents were looking around like, 'Who knows these songs as a 10-, 11- or 12-year-old?”

Manning still has that curiosity about his old classmates.

“He loves nostalgia, the childhood memories,” Montgomery said. “Every five years you have your high school reunion, and nobody’s more interested in what our classmates are up to or getting an email chain going: 'Where are you? Who’s going to be there? How is so-and-so doing?’ There’s this keen interest in looking back.”

Not surprisingly, football factoids were of particular interest. There, he was a walking Wikipedia.

“He knew every single player his dad played with,” Teaford said. “He knew every single play. He would listen to the radio broadcast and he would tell you exactly what the next play was going to be, who the receiver was that caught every touchdown, where they were from, what their brother's name was. He could tell you stories about people he'd never even met.

“The light switch didn't just go off when he started playing quarterback at Newman or got to Tennessee or got to Indianapolis. The light switch was on from the second he was born.”

A sticky solution

Did you ever watch “Homeland” or “The Wire,” where crime solvers would construct a wall of photographs or thoughts tenuously connected by pieces of string, a crazy visual aid untangling some type of convoluted conspiracy?

Basically, that was Manning’s bedroom.

“Back in 1993, we didn't have computers in class, nobody had iPhones,” Stibbs said. “So whenever he had an idea, he would write it down on a little yellow sticky note.

“You'd go to his room at his house and he'd have 250 sticky notes all over his wall, just on little ideas that flashed into his mind that he didn't want to forget about. So he kept a note and a pen in his pocket and he'd write it down. I always thought that was pretty incredible at that age to have that attention to detail.

“It could have been a homework assignment, something that popped into his mind. Something about watching game film or practice or preparation. It was all over the board.”

The crying game

Sometimes, Peyton was too smart for his own good — or at least he thought he was.

He was on a “bitty basketball” team when he was in grade school, and a teammate’s dad was the coach. The guy was a lawyer who lived in the Mannings' neighborhood, and though he didn’t know a lot about coaching, he was focused on the kids having fun.

That didn’t sit well with young Peyton, not after the team lost a game.

The coach tried to give the team a pep talk in the wake of defeat, sort of: “Well, we didn’t play our best, but we’ll get ‘em next time.”

Peyton stood and countered with: “No, the reason we lost is you don’t know what you’re doing as a coach.”

Manning still cringes at the memory.

“I was dead wrong,” he said.

What’s more, young Peyton was in trouble with his own father, Archie.

“My dad couldn't hear what I was saying,” Manning said. “He just saw me pointing my finger at the coach, and he could tell that I was out of line. Made me go over to the coach's house that night and apologize. I remember I was crying. I was bawling and my dad was saying, 'I'm not going to let you play next week.’

“The coach was very nice, accepted my apology and said, 'No, I want you to play.’ It was a good learning lesson for me of what's right and what's wrong, being coachable and keeping your mouth shut. That was the most valuable lesson in that. My dad straightened me out real quick.”

Clash of the Titans

When it came to high school coaches in Louisiana, Billy Fitzgerald was larger than life. He was the head coach of two sports at Newman High for a combined 60 years, with his teams winning five state titles in basketball and two in baseball.

The 6-foot-5 “Coach Fitz” was a commanding presence whose decisions from the sideline or dugout were seldom questioned.

Then along came Manning.

“Peyton was a pretty intense, competitive personality as well,” Keck said. “I always thought to myself, man, when coach Fitz is upset you just kind of nod your head and, 'How soon can we move on and get out of here?’ Peyton, he would butt heads with him. He would go after him, they would get into it with each other. They were very competitive.

“Those who played basketball probably noticed the most tension between those two. It was all healthy. It was all in the pursuit of excellence. But I remember they would get into it, and I was like, man, he's the guy who makes me run wind sprints. I'm not going to fight with that guy. I just tried to get out of there as quickly as I could. I didn't have the guts to have words and decide I had something to say back to him.”

Naked and afraid

Then there was the time Manning and his Newman baseball teammates were on the road for a tournament and stayed in a motel the night before their semifinal game. Fitzgerald reminded them to grab towels because they’d be showering before their five-hour bus ride home.

When Manning got off the bus to get a towel, Stibbs asked him to grab him one too. Prankster Peyton returned with a towel for himself and a tiny washcloth for his pal.

That was fine and funny until Newman blew a big lead and lost a game it shouldn’t have lost. Fitzgerald was fuming. The disappointed team, sheepish and silent, hit the showers, and Peyton’s friend brought his washcloth, figuring he’d quietly exchange it for the full-sized towel of some unlucky freshman.

The towel swap happened, but the guy who wound up with the terrycloth postage stamp was the hotheaded coach Fitz, who emerged from the showers naked, soaked and steaming mad. He demanded to know who had left him with a washcloth.

“I remember looking over at Peyton sitting in the corner, and he was just hunkered down,” Stibbs said. “He wouldn't look at anybody. And I remember thinking, 'You almost got us killed because of your little prank.' We still tell that story every time we get together once a year. It's etched into all of our memories.”

Manning’s defense can be summed up in three words: not my fault.

“That was on Stibbs,” he said. “I was simply pulling a prank on my friend. It should not have gotten to the head coach. So that's all on Stibbs. I'm not taking the heat for that one."

The imposter

Manning was no stranger to mischief.

“When we weren't water-ballooning cars at Thad's house as teenagers, we did a lot of prank calling,” Montgomery said. “This was prior to Caller ID when you could actually get away with calling someone and acting as if you were someone else.

“It was always better to prank call a parent, because they were naïve and gullible and easier to go through with it, versus a peer who was going to recognize your voice.”

Some of the most memorable gags involved Manning posing as a reporter for a publication that specialized in rating high school football players for fans and college recruiters.

“He had this idea that we would call some players' dads of one of our rival teams and act as if we were of Blue Chip magazine inquiring about their son,” Montgomery said. “So Peyton would get on the phone and call someone's dad, an acquaintance, and act as if he was someone inquiring about their son.

"'Hey, I hear your son's a rising senior and a football player, can you tell me a little bit about him?’ These dads just took it hook, line and sinker. Everybody wants their son to be the next great athlete. So [the dad would say], 'Oh, yeah, he plays both ways, linebacker, running back. Runs well. Works out in the weight room.’

“We would just pry and ask the most ridiculous questions and get into, 'What does he power clean? Does he wear a neck roll? Does he wear a Breathe Right?' Just see how far we could go with it. We got some good laughs out of it.”

It worked until it didn’t. Manning was nabbed when he left a voice message for someone and that person recognized the voice.

“He got in trouble,” Montgomery said. “I think Archie received a phone call, and he had to apologize to these dads for those prank calls.”

Self-made Manning

Manning is the son of an NFL star quarterback. His genetics certainly helped. But he didn’t stroll into high school as a phenomenal athlete. He was slow and skinny, and it was his relentless work ethic that molded him into the player he became.

“People make assumptions that because Peyton had all the success he had that he was born fast, born able to jump high, strong,” Teaford said.

“But we used to do a speed camp with the track coach when we were in the eighth grade. There was a heavyset guy who would run with us, and Peyton was running with him. In eighth grade he was probably close to a [6-second-flat 40-yard dash].

“When we went into the weight room, he practically couldn't lift the bar. It's a testament to who he is. It's not where he started, it's where he got to in the end that matters. I bet by his senior year he was probably running a 4.9[-second] 40 and I know he used to talk all the time about how much stronger he got at Tennessee. It's pretty amazing. It's not like he was born with that talent.”

Manning routinely would gather his receivers for impromptu workouts, and it was always with a purpose, not just to toss around the ball. Keck, who was a tight end, remembers the quarterback directing him to run five-yard out routes over and over.

“I didn't understand that the five-and-out was critically important for spreading out the defense,” Keck said. “All I knew was it was the most boring play ever. You're going to catch it and go out of bounds or get killed. You're going to get four, maybe five yards if you catch it.

“I would do it 18, maybe 20 times and I was like, 'This is so boring. Can we do different routes? Can we do a post or a long touchdown catch?’ But he understood the strategic nature of the timing of that route with each receiver. He was probably working on making sure that as soon as I swung my head around the ball was right there. Meanwhile, I'm just complaining. My feet hurt. I don't want to catch another five-and-out. It's just not that fun.”

The lesson?

“He got to this point where he decided he was going to be the best, and he just put his head down,” Keck said. “He out-prepares anybody.”

Along for the ride

Manning will be up on that stage in Canton, but his high school teammates and friends in the audience will feel as if they’re standing right beside him.

“It's been a long journey for all of us,” Stibbs said. “We've been going to the games when he was in Knoxville in college every year. For the 18 years that he was with the Colts. In Denver, we would go to games every year. It almost feels like we're going in with him. We've been part of that whole experience, that whole journey where it's consumed our lives too.”

Said Montgomery: “Selfishly, I don't think we ever wanted him to retire. It's such a part of the last 20-plus years, whether it was going to Denver or Indy or some other NFL town to go watch him play, and how proud we were to be a part of it, and our families a part of it, whether it's our spouses or kids.

“We knew five years after retirement he was going to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer, and here it is. It's crazy to kind of put that cherry on top.

“He's exceeded expectations every step along the way.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.